Meet the child soldiers of Yemen, sent into battle by adults

TAIZ, Yemen - Saeed is on holiday, staying at his parent's house. It's in al-Maafer district, one of Yemen's poorer areas, and reflects the life of the village.

The first floor houses the family while the ground floor shelters cattle, on which many residents depend for their income. There is also the mango crop but it can only be harvested for two months every year. Electricity is scant, drawn from solar panels and only used for lighting.

Outside the family home, overlooked by hills, it is silent, bar the sound of rain. The smell of damp earth permeates the air.

At 17, Saeed is taller than most teens his age. He wears a relaxed uniform, common the world over: open-toed sandals, sand-coloured chinos and a checked shirt.

But Ahmed is not a typical teen, even in Yemen. He's a battlefield soldier and has been fighting with the pro-government forces loyal to president Abd Rabbuh Hadi since he was a 15-year-old schoolboy, swapping textbooks and classrooms for ammunition and army barracks.

Saeed is the youngest of three sons (he also has three sisters). Like the rest of his family, he asks that his real name is not used amid fears for his safety.

His brothers, Ahmed, 38, and Khalid, 36, did not complete their full education, instead joining the army on the same day 17 years ago, saying that it was the duty for "brave people".

Initially, Saeed was going to join too when he graduated at 18 from secondary school. But when war came to Taiz in March 2015, his father Murad told him that if he ever wanted to fight on a battlefield then now was the time.

'Age is not a problem when it comes to fighting. But heart… If a man has brave heart like my sons, then he can fight'

- Murad, father

A retired soldier himself, Murad is slim, tall and in his 50s, yet seems much older. He can hardly walk: when he does, it is only with the support of a stick. When he speaks about the war, his loyalty to the government is evident, insulting anyone who even hints that they disagree with his views, even in jest.

Aside from his own children, he has encouraged other children in the village to sign up and serve. "I do not consider him to be a child," he says of his youngest son. "He has a body and heart that many adults do not possess. Age is not a problem when it comes to fighting. But heart… If a man has brave heart like my sons, then he can fight."

Minister: Send kids out to fight

Child soldiers have been a constant feature of the war in Yemen since it began in 2015. At the start of the conflict, UNICEF said that under-18s accounted for an estimated third of all troops.

Both the Houthi rebels and pro-government groups initially pledged to end the practice – pledges, UNICEF says, that they have now broken.

Murad is not the only one suggesting that children fight. Hassan Zaid, the minister for youth and sports in an administration set up by the Houthi rebels, suggested on 20 October that school classes should be suspended for a year so pupils and teachers could be sent to the front.

"Wouldn't we be able to reinforce the ranks with hundreds of thousands (of fighters) and win the battle?" he wrote on Facebook.

In February, Amnesty reported on Houthi recruitment of boys as young as 15.

The situation has been exacerbated by the breakdown of Yemen's civil administration. In certain parts of the country, especially the north, teachers have gone unpaid for months and schools have shut: some academics have even taken to the battlefields themselves and ended up fighting alongside their pupils.

Jamal Aidarows, a teacher formerly employed at al-Fawz school in the Bani Shaiba area, told Middle East Eye in April: "When I entered the military camp for training, I found two of my former students receiving training in the same camp. Really, they were braver than me to join the battle before me."

Children, with nothing else to do, have been attracted by the relatively high wages offered by fighting – far above the $50 average monthly wage for a labourer - as well as the draw of the army.

'When I entered the military camp for training, I found two of my former students receiving training in the same camp'

- Jamal Aidarows, teacher

Jamal al-Shami is the president of Democracy School, a child advocacy NGO based in Sanaa. He says that child soldiers are now a common sight in Yemeni life, fighting on battlefields and manning checkpoints.

"Most of them [the child soldiers] are from poor families because the warring sides exploit their need for money," he says. "It threatens the future of the children. Many families have forced their children to join the battle for the sake of money."

But then there are parents, like Saeed's, who encourage their children to go to war for what they regard as moral reasons. Saeed says that relatives and friends have all been supportive of his actions: indeed, he was told at the age of 10 that someday he would become a soldier.

Murad adds: "Even if I lose all my sons in the battle, I will not regret it because I am a soldier. I know very well how to serve my country."

Brothers in arms

Saeed spent less than a month training at the Khiami military camp, 30km south of Taiz city, under the supervision of Ahmed, and learned quickly.

Like many Yemenis from a rural region, he is used to handling a Kalashnikov. Most families have at least one rifle, which is fired into the air during celebrations such as weddings: even before the war, Yemen had the second-highest rate of gun ownership in the world behind the United States.

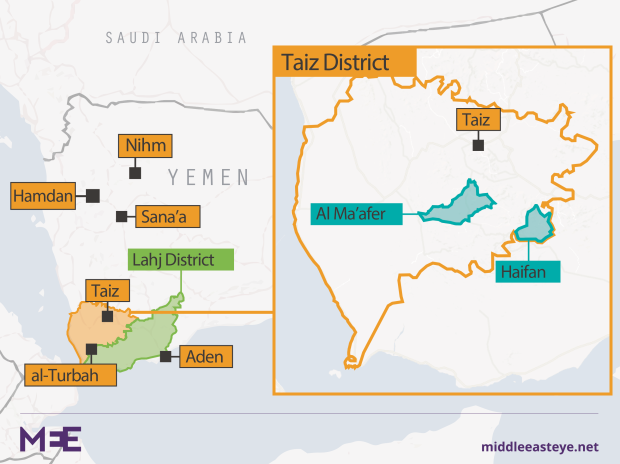

Soon Saeed was sent to fight in Haifan, a region of hills and valleys within Taiz province.Seventy kilometres to the north lies the city of Taiz, the regional capital; to the south and east is the neighbouring province of Lahj. Both the government forces and the rebels have been battling since 2015 for control of a key supply route nearby to the strategically important port of Aden.

'For a few weeks I observed the older fighters and how they work. Then I started to shoot'

- Saeed, child soldier

Saeed's brothers advised him on how to observe the enemy without being detected; also how to enter and leave the conflict zone without falling victim to snipers. "I did not take long time to learn fighting skills because my favourite subject at school was Islamic education," Saeed says. "That includes a lot of stories about the battles of our Prophet Muhammad and his bravery.

"I do my best to imitate him. For a few weeks I observed the older fighters and how they work. Then I started to shoot."

Saeed's role was to provide covering fire against the Houthis, either when they tried to advance or else when his own side went on the offensive. He says he doesn't know if he killed anyone: he was simply firing randomly.

Initially he could not sleep for several days because he feared for his safety. "On the first day, the sounds of shelling and shots frightened me. I was ready to leave the battlefield. But the words of my father prevented me from doing so, as I would be a coward if I left. After a few weeks I became used to them and realised that they would fall far from me."

What Saeed valued on the battlefield, apart from serving his country, was the comradeship of fighting alongside friends he met on the battlefields or in the camps.

Instead he fights alongside professional soldiers and receives YR2,000 ($5.2) per day, the same pay as an adult fighter and far higher than the monthly wage for a Yemeni labourer. He has no uniform and goes to the battlefield in the same casual clothes he is wearing when we meet.

"Every day I buy qat, carbonated drink, and water for YR1,000 ($2.6)," he says in reference to Yemen's popular narcotic plant. "Qat is necessary for work so I can stay alert at night."

But qat has also made him an addict and he cannot now live without a bag of green leaves. Nor can his friends: between fighting they gather to chew the green leaves, reminiscing about life back in their village, talking about politics and making plans for when the war ends.

"I work like any other soldier," says Saeed, "but I prefer to chew qat with my old friends."

The cynicism of war

But life for this child soldier changed on 11 December 2016.

It was a Sunday. The Houthis were advancing from Haifan district towards the main road between Aden and Taiz. "Our leader gave us directions to confront the advance," recalls Saeed, his speech becoming more emotional.

He was directing covering fire as usual when a friend shouted above the sound of battle: "Your brother has been injured!"

Ahmed, stationed only 50 metres away, had taken a direct shot to the head from a Houthi sniper. Saeed ran over but it was too late – Ahmed was already dead. He was 38.

"My parents and siblings did not cry as they believe that my brother will go to heaven," he says. "Dozens of my colleagues have been killed and injured near to me but none of those affected me as much as my brother. I still think of him and pray for him every day."

Saeed remained at home for a month to mourn, then returned to the battlefield. In early 2017 he was transferred to the city of Taiz and the security detail of a government military leader, although is still called on to fight.

'Dozens of my colleagues have been killed and injured near to me but none of those affected me as much as my brother'

- Saeed, child soldier

"It is an honour to be a guard of a brave military leader who has devoted his life to serve the country and stop the advance of the Houthis," he says. "I am also devoting my life to serving the country. I do not fear death. Rather I want to follow my brother to heaven."

Saeed has now been a child soldier for more than two years, but has become cynical about who will win the war, dismissing the idea that pro-government forces – or, indeed, any side - will claim ultimate victory. "We could not recapture Taiz from the Houthis. That means the only solution will be political and not military."

And the future?

"When the war stops, I wish to complete my work as a soldier and then be promoted to colonel in the Yemeni army. I have served the country in difficult conditions. I want to receive a proper reward after the end of the war."

Victory or martyrdom

And then there are the Houthi rebels who Saeed is fighting. They too use child soldiers, like Rasheed, 16.

Like Saeed, he asked that we not use his real name. He lives in Hamdan, west of the capital Sanaa, where many residents back the rebel Houthis. He stopped studying when he was 12 - work, he says, is more important to his family than education – and helped his father and three brothers sell qat in Sanaa

Rasheed has now been fighting for a year. But his family are not poor and do not want for food: instead Rasheed signed up as part of the wave of Houthi support from the region.

"I am fighting to liberate my country from the Saudi-led invasion," he says. "My father is against the Saudi-led offensive, which destroys our country, so he encouraged me to do it. Also, I talked with my friends who had already gone to the front."

Rasheed did not receive any military training, but took his own rifle – given to him by his father when he was 12 - and headed for the front at Nihm, around 70km from Sanaa.

"I do not have enough experience to work in battle and face-to-face clashes," he says, "so fighters like me stay behind the ridge until they have enough experience.

Rashid worked with around five others in the same postion. For the first month he simply observed his colleagues shooting.

Wearing the same qamees that he wears on the battlefield, he speaks with an earnest seriousness, as if he is more than twice his age. "If you are far from the battlefield, you imagine it is difficult to shoot the enemy. But then you go there and you find it it easy to do."

He has two roles. The first is to fire on advancing pro-government fighters. Then, once the fighting is over, he and his friends carry away the dead. Some of his peers have also been killed.

'Martyrdom is the purpose of our fighting. We are fighting for either victory or martyrdom'

- Rasheed, child fighter

"The families of the martyrs celebrate when their sons meet their fate in the battlefield because they are martyrs," he says. "They will go to heaven, so martyrdom is the purpose of our fighting. We are fighting for either victory or martyrdom."

He thinks that Saudi Arabia will eventually be forced back and have to defend its own borders, at which point the Houthis can declare victory.

And when the war is over, what will he do?

"I hope to resume my former work as a qat seller and establish a new qat market in Sanaa."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.