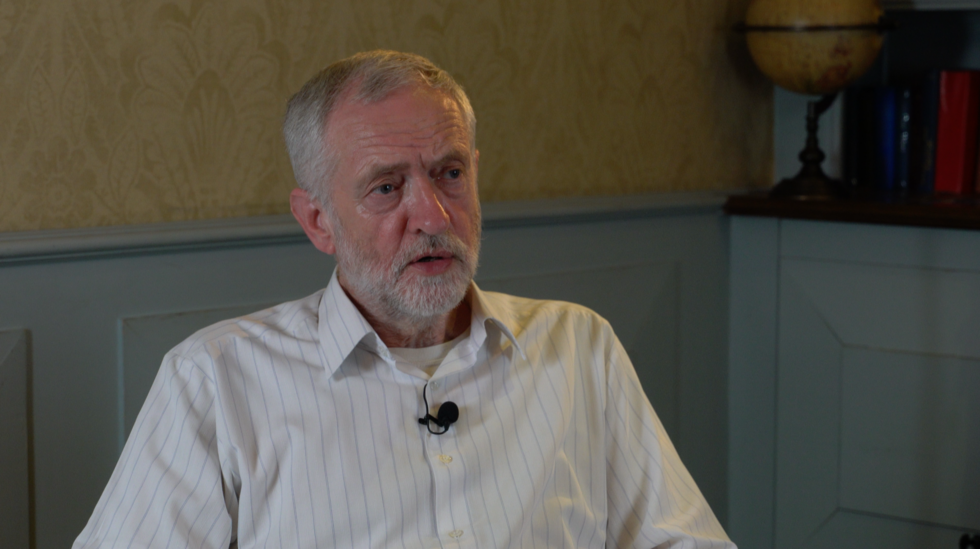

Middle East Eye meets Corbyn: The full interview

Middle East Eye's David Hearst and Peter Oborne sat down with Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn. This is the full transcript of the conversation.

David Hearst: So the first question I’d like to ask you is if, as we all expect, you are re-elected, do you expect the majority of Labour MPs to respect the wishes of party members?

Jeremy Corbyn: Yes I do. Because we have to get together as a party. We’ve got to put forward a credible alternative to this government on issues of equality and justice, housing, education and economy. And we’ll do all of that and I fully expect after this contest is over there is going to be a coming together. Indeed, I’ve done my best to reach out to lots of Labour MPs even though I know many of them voted contrary to my wishes on the conference motion. That’s ok – we can go forward.

DH: The history of your leadership has been you battling against this tide of hostility. And I just wonder how you’re going to turn people around like that…

JC: Well, I’m very calm and very generous so it’s fine.

DH: But they’re not going to change their views are they? These are acrimonious attacks. They’re taking your policies and saying that they’re their policies. They’re saying basically anyone but Jeremy Corbyn. Now surely that is fundamentally an undemocratic thing to do?

JC: Well I was elected with a very large majority within the party. I recognise I had very limited support from within the parliamentary party. And I think some of them are confusing the position of the parliamentary party with the party as a whole. The parliamentary party is very, very important but it is not the entirety of the Labour Party and I have reached out in a way no other leader ever has in appointing people to my shadow cabinet last September who were very critical of me.

Some of whom remained critical within the shadow cabinet. There were some adjustments made to the shadow cabinet at the turn of the year, and then there were the resignations in May. I regret all those resignations. I have replaced all those people with newer MPs, very hard-working MPs, and I will be reaching out to all sections of the parliamentary party after the election.

Peter Oborne: One of your shadow ministers [Sarah Champion, a shadow Home Office minister] un-resigned rather sensationally earlier this week – do you expect any others [to do the same]?

JC: Yes I do. Sarah contacted me to say that on reflection she’d like to carry on doing the job and I said, on reflection, I’d love you to carry on doing it. So we had a very pleasant exchange and it’s fine and she’s carrying on. And I think that there are one or two others that are in the same position.

'I was invited to resign. I absolutely refused to do so. I’m responsible for the mandate I was given. I will carry out that responsibility – and so I have. And I carry on doing that'

DH: Nevertheless, the attempted coup has had its own effect, certainly in terms of the polls. Before, you were level pegging in the polls. Or even better than the Tories. Now, consistently the polls are showing - the latest YouGov poll shows that you’ve lost 2.5 million voters to the Tories and in the northeast there are problems - a lot of those votes have gone over to UKIP. How, from the opposition benches, are you going to recapture that Labour support?

JC: Well, first of all the coup is obviously not good news from the point of view of the party’s image. I regret that it happened. I was appalled at the way it was conducted and the way it was designed to cause maximum damage to the party, day in day out. I was invited to resign. I absolutely refused to do so. I said I’m responsible for the people who elected me. I’m responsible for the mandate I was given. I will carry out that responsibility – and so I have. And I carry on doing that.

How we reach out to people is to recognise that the [European Union membership] referendum result produced quite conflicting results across the country. London voted overwhelmingly for remain and in the strongest Labour constituencies in London there were massive remain votes. I think Lambeth and Hackney and Islington, Lewisham were the biggest remain areas.

The biggest leave areas were actually equally strong Labour areas in the northeast – Sunderland, old mining towns across Yorkshire. How we reach out is looking at the issue of "left behind Britain". Places that were once proud mining towns, proud industrial towns lost their steel industry, lost their coal industry, lost their manufacturing base – never been replaced.

Wage levels are much lower in de-industrialised places and those jobs [were] replaced with insecure or zero hours contract work. So the lowest wage area in the whole country is now Boston in Lincolnshire. It also had the highest vote for UKIP in the whole country. I think there’s a connection there.

We have to reach out. We have to reach out on employment policies. We have to reach out on investment in infrastructure, investment in industrial development. Reach out with a national investment bank that will invest in growing manufacturing industry in the way that Germany has done over the past 40 years.

If you take the 1970s as a kind of change point in economic strategy, when the rolling back the state agenda came from Reagan and from Thatcher in Britain, Germany went in the opposite direction in investing, in sustaining its manufacturing industry. So we’ve gone a trajectory of a sort of development of service at the expense of manufacturing.

I’m not saying it’s all totally simple but in Germany they’ve maintained a very high level of manufacturing industry by going into high tech areas – I think that’s the direction we’ve got to go. And so I want to reach out to those communities on that message – but also, quite simply say this: UKIP might give you a message which says your problems are caused because somewhere in Britain there are some Polish workers, somewhere in Lancashire there are some Lithuanians working.

None of that prejudice is going to build a house, build a school, recruit a new doctor or anything else. It has to be about investment in communities. It also has to be about ending the undercutting of wages by exploitation of the free movement of labour.

Which is why throughout the referendum campaign I made a great deal about [closing the loophole in the EU] workers’ directive, which then would prevent this undercutting of wage and industrial agreements in Britain.

So I’m very strong on that. I say that as a former trade unionist, who always used to argue that we shouldn’t have legally binding industrial agreements. I think it’s time to think again about this. So where there is an industrial agreement in the construction industry that you will get X pounds per hour if you’re a steel erector, Y pounds an hour if you’re a bricklayer, Z pounds per hour if you’re a plasterer – those should be the minimum that is then enforced in the industry to prevent this degree of bringing in of a whole lot of underpaid, equally exploited workers in order to undercut them.

PO: Would you see a situation where we’d have a second referendum?

JC: Not in the immediate future and I think one has to respect the result of the referendum, unpalatable as it is for those that wanted to remain. But I do think we now have to embark on serious negotiations with the European Union as well as the European Economic Area – the two are obviously closely linked - as to the kind of market access we are going to have in the future.

I suspect the debate that’s going on in the Conservative party at the moment is between those that would go for an EU membership-lite-type approach, where you have a kind of market relationship with the European Union. And those that would go for an offshore bargain basement economy, where we have low levels of corporate taxation, lighter touch regulation and then offshoring of industries and services into Britain on the fringes of Europe – that will lead to a very difficult relationship with Europe but won’t actually improve the circumstances of people in Britain. So I think it’s that debate that’s going on at the moment.

PO: You said no immediate referendum. So you are holding out…

JC: Well, at some point in the future somebody might say we ought to have a referendum on how we deal with the future with Europe. I think we have to come from the point a referendum was called, a debate was held. The referendum gave a result and parliament has got to work with that result. The idea to call a petition to call an immediate referendum now is not a good idea.

PO: But another one, perhaps on the terms of Brexit?

JC: I’m unpersuaded.

DH: A lot of people voted out of ignorance. A lot of people voted ‘no’ out of ignorance.

JC: I think we want to be careful about saying people voted no out of ignorance. We’re in a democracy. You give people the right to vote, they have the right to it, they exercise that right. It is up to parliament to live with the consequences of it.

'I want to mobilise people rather than devolve all power to focus groups and technocrats'

DH: Do you agree that something historical is happening to do with the British political scene and also the European political scene as well? And that is that the old certainties and the structure of British politics is changing, and you’re part of that insurgency – your vote is part of that insurgency as well?

I’m thinking that what’s happened, for instance, to Labour particularly in the northeast is quite similar to what happened to the French Communist Party in the south of France where a lot of their votes now go to the National Front. Under New Labour the working class felt betrayed and didn’t have Labour next to them. You’re trying to reverse that. Do you think there’s something really profound happening to the Blairite, Cameronite centre of British politics that basically tried to bully people?

JC: I think it’s a question about political power and influence. And the New Labour project was very much Third Way economics, it was aggressive foreign policy, and it was essentially marketisation of a lot of public services. I’m trying to take things in a very different direction of a human rights, democracy-based foreign policy rather than an interventionist one. And an economically interventionist economy in Britain and in order to promote good quality jobs and employment as well as promote decent levels of public service.

Yes there is an interesting series of movements around the world. In Britain it’s very large numbers of people coming into the Labour Party and being activated around the Labour Party. So we’ve got this enormous membership. If you add in the registered supporters, we’re looking at three-quarters of a million people involved in a political party. More people signed up to vote in the Labour election in two days than the entire membership of the Conservative party – that’s in addition to the existing membership that was always there.

Likewise in the USA, the campaign around Bernie Sanders was in a sense a parallel to much of the campaigning work we’ve been doing here. We’ve had some very interesting discussion with Bernie Sanders’ campaign on the way they’ve conducted things and the issues they’re conducting them on.

And so, whilst Bernie Sanders obviously isn’t the candidate for the Democrats, the Democrat platform reflects a great deal of the arguments he was putting forward on corporate taxation and tax evasion, on investment and intervention. In a sense Obama went further than most European countries on intervention during the post 2008/9 crisis in that he intervened to take temporary public ownership of large sections of the car industry.

I think what’s happening in the USA is interesting. Likewise in Europe. Social democratic parties that have gone down the traditional market route of New Labour and the Third Way such as PASOK [the socialist party in Greece] are now almost obliterated as parties and have suffered grievously. Those parties that have actually offered something different, some alternative – in a sense some combination of traditionalist socialist values as well as a more up-to-date form of dealing with economic intervention - are actually the ones that are doing well.

And it was when I went to the most recent meeting of the Party of European Socialists in Paris, they all wanted to know how we recruited so many members. They said have you got a special recruitment app or something like that? I said no. It is nothing to do with apps. It has got nothing to do with recruitment methods. It is about the political message we are giving.

DH: So your message is that you’re going to be able to translate that membership into votes. You’re no longer talking about middle England?

JC: We have to campaign in all parts of the country and reach out to what I term "left behind Britain". Because that’s what it is and feels like. And so you have to give some hope and some determination to those communities and that’s what we’re trying to do.

PO: So you do accept our proposition that there is a fundamental, seismic political structural change in Britain going on at the moment?

JC: Yes, I think there is because it’s an involvement of a new audience in politics who felt very disillusioned. It is very difficult to measure everything on the basis of personal contact, emails, postcards, whatever it happens to be. But I meet a significant number of people – a significant number of people have contacted me and said “I’ve now become interested in politics because what I see with the Labour Party at the moment is that you’re trying to reach out in a way that no one has reached out before.”

See in the past, politics in Britain was always conducted on the basis of a contract. The political party is the provider; the voters are the consumers. And so say you vote for us and we will give you Y. Instead, what I’m trying to say is yes we will try to do all those things but it’s a question about empowerment of the community.

So take the energy policy we are putting forward, I am not arguing for the nationalisation of the Big Six energy suppliers. What I’m arguing for is the community production of energy on the German model actually. It’s not that revolutionary. It’s local authorities, cooperatives and consumers doing that, which is more economically sustainable and more empowering of the community because the alienation level that exists all across Europe due to big business is huge.

PO: That wasn’t really the question I was asking. The question I was asking is that New Labour and the Cameron Conservatives – the modernisers in both parties – devised a new structure of politics which was in many ways parasitic on the old party system. Power was transferred from voters to focus groups and technocrats. It was a battle for the middle. Now what you are doing in Labour is an attempt to return to the base. Is that right?

JC: That’s a fair way of putting it. It’s a round of new ideas and a return of power from the base, particularly of young people. Only half of young people registered to vote in the last election – less than half, 47 percent I believe. What we are now seeing is a big increase in voter registration of all ages. Partly [because of] the referendum, but maybe other reasons as well. And a growing interest and involvement of many young people in politics.

So take the Obama 2008 model. What Obama did was he didn’t play to the tradition of we will mobilise X number of middle-ground people. He actually expanded the electorate by voter registration and by campaigning. Because we now have an, I think, very unfair form of voter registration, it is now possible to expand the electorate. Now boundary changes are coming and there are all sorts of issues there, but it’s about mobilising people and giving them hope and confidence. That’s what I’m trying to do.

PO: Could you see there being a change in the two-party structure coming along at some stage?

JC: While we have a first-past-the-post system no – I don’t see any huge change. But there’s a big but, and a big caveat in that. The political history of Britain is that the high noon of the two-party system was 1951 when I think 91 percent of the electorate voted for either Labour or Conservative on a very high turnout. Eighty percent turnout, 91 percent voted for the two parties. Ever since then there’s been a decline of the proportion of the two parties to 60 percent.

PO: And also of course a catastrophic collapse in party membership until you reversed that.

JC: Indeed. Across all parties there has been declining membership and this has been something that has been reversed since we started this whole process a year ago. And I think we should be forgiven for involving a very large number of people in politics who never had before. It’s not about individuals. I’m not the big dictating personality.

PO: The internal struggle inside Labour strikes me as one between you and your allies who want to bring back ideas and energy to politics and the Blairite/Cameron model which is that you abolish politics almost and regard ideas and political tactics as purely instrumental in the battle for power.

JC: I want to mobilise people rather than devolve all power to focus groups and technocrats. Mobilising people makes life often very uncomfortable for lots of people, but people should never be comfortable when they’re in power.

DH: What do you regard as your successes in a very, very embattled year?

JC: Turning the party into one that challenges the economic orthodoxy of austerity, of rolling back the state, of cutting. And interestingly everyone has joined in now. I was very pleased when [former chancellor] George Osborne finally came on board and abolished the fiscal rule. Thank you, thank you George. Unfortunately he lost his job the next day but there we go. I think that’s important.

Secondly, we have managed to defeat the government on a number of issues. A year ago the party was abstaining on the welfare reform. About a year ago this week, Harriet Harman was saying to the party we lost the election because of welfare. We can’t be seen to be supporting welfare. That is now totally reversed. As I said we defeated them on working tax credits and we’re now resolutely in favour of a much stronger welfare state and disability cuts. So the government’s defeat on personal independence claims was absolutely huge for a lot of reasons. So I think those are the big achievements.

Also, I pledged during my leadership campaign last year that I would deal with the issue of Iraq, I would deal with it when the Chilcot Report came out and I would issue a full apology for the Labour Party’s involvement in the invasion of Iraq and I did it.

'What happened in Iraq was so eminently predictable. I’m no great soothsayer'

DH: Talking about Iraq, Chilcot is one of the things that has really vindicated you and one of the things I did was to go back and hear your speech again that you made in Hyde Park, which actually stands the test of time, I think that was in 2003. It was an enormously impressive speech not only for its accuracy.

But what lies next? Do you agree with, for instance, Alex Salmond, who says that Blair should face some judicial or political reckoning? There’s this whole sense within the New Labour project that they got away with it. Even their mistakes they got away with and they are fantastically rich and they go off round the world. Do you support the families of the bereaved soldiers who are now trying to take a private case against Blair? What about this whole pressing issue of accountability?

JC: I was intensely involved as you know with the whole run up to Iraq from Afghanistan onwards and it’s kind what you said about my speech in Hyde Park that day. I’m surprised that in the midst of the 20 other speeches made that day it’s been rediscovered, shall we say.

But I’m pleased in that sense. What is sad is that what happened in Iraq was so eminently predictable. I’m no great soothsayer. I could just look like anybody else could and say, hang on, if you create the idea that Saddam Hussein is promoting terrorism all over the region and Islamic fundamentalism at that, you’re then justifying your invasion on that basis. You’re then going ahead and destroying the state, which is what the West did.

You then disarm the … Well, you send the army to the four corners of the country with its weapons. Ergo, it’s not surprising that you end up with the chaos and loss of life in Iraq and so I just find it very sad and very depressing we’ve then had the spin off of all the other problems in the region. So I take no comfort from that but that is what many of us thought would happen.

So we then go on to the reckoning. Well we’ve had a number of inquiries on Iraq – we’ve had the select committee inquiry, we’ve had the Butler, we’ve had a number and then eventually Chilcot came along. And Chilcot is actually a very clever, if very English, piece of writing.

I don’t know how much of it you’ve managed to read. I mean are you up to half a million words? It is very interesting the way it’s presented because at one level it’s a great deal of understatement and lots of caveats all over the place. But it becomes absolutely clear as you go through it that the issue of the legality was open to a huge amount of debate and not properly presented to Parliament.

The issue of breaking up the Iraqi state was an act of policy, as much by the US as by Britain in this. And the culpability of the information given by individuals to Parliament has to be taken into account. Now Chilcot kind of leaves it open. Then you add into that the ICC’s proposals and the words I said during the apology [were]: “Those that are responsible for the war in Iraq must be prepared to face up to their responsibilities”.

'People must face up to their responsibilities for what they did. I met the families of the soldiers who died and when you meet a family of anyone who has died it’s very hard... And then it becomes apparent that the war was based on misinformation or deception... It’s very hard for those families to come to terms with that'

DH: So the answer is, yes, you do favour…

JC: There has to be. People must face up to their responsibilities for what they did. I met the families of the soldiers who died and when you meet a family of anyone who has died it’s very hard. I meet the families of young people who have been stabbed to death. It’s very hard for them to understand their son’s life has gone through a random act of violence.

If you join the army, in a sense you join knowing there are risks involved. Obviously. And then you die in a war like Iraq. And then it becomes apparent that the war was based on misinformation or deception, that it wasn’t a necessary war, that is wasn’t a defensive war, and your son or daughter has died in that particular conflict. It’s very hard for those families to come to terms with that, so I spent a lot of time over the past years talking to the families of those that have died. They are very, very impressive people. I think the way Reg Keys and Peter Bradley have conducted themselves is very, very impressive.

They are not the only ones. There are others as well and I just think that politicians who accept the idea and vote in Parliament – and cheer when you do it – to go and bomb somewhere, and for somebody else’s children to die, should think very, very carefully about that. We as a country have got to feel very carefully about this and the absolute minimum coming out of this has to be a War Powers Act. So that Parliament has to be consulted. There has to be a vote. And every MP has to take responsibility.

DH: Talking of the War Powers Act, Middle East Eye has done quite a lot of work establishing the presence of British troops fighting in Libya. Now do you accept that there is some sort of sliding mandate which has empowered British tornadoes to bomb Iraq and Syria and suddenly this slithers over to Libya.

JC: Yes, I’m very concerned about this because the prime minister – or when David Cameron was prime minister and I should imagine Theresa May would say much the same – would say parliamentary convention now requires that for the deployment of British troops there has to be a parliamentary mandate.

Except – and they’ve all used the except – when there are special forces involved. The question of this of course goes back a long way to Vietnam 1963, when the US managed to have I think 50,000 advisors to the South Vietnamese government before Congress was even invited to vote on whether or not it should be involved in the Vietnam War. I think the parallel is a very serious one.

Clearly Britain is involved. Either through special forces in Libya or through arms supplies to Saudi Arabia to the war in Yemen. And indeed by the same process to the supply of anti-personnel equipment that is being used in Bahrain by Saudi Arabia. So I think we have to have a War Powers Act that is much more watertight on this.

[Labour MP] Graham Allen has produced some very interesting proposals on a War Powers Act which, if we don’t get to discuss and don’t get the opportunity to vote on in this Parliament, I think that should be something that Parliament as a parliamentary matter should vote on. Then it would be up to a future Labour government to bring it in. I would see it as very important.

PO: So in other words you’re asking for a change on doctrine?

JC: Doctrine must include military involvement, not regular forces because the special forces argument [drives] a coach and horse through the principle.

PO: At some point would you then say that we should have a vote on the British military involvement in Libya, whatever it is?

JC: I think we need a clear statement of what the involvement is followed by a discussion on it. Yes.

PO: And then a vote on it?

JC: Why not? Because it seems to me if there is this significant involvement and it keeps on coming up. The idea we went to bomb Libya because of the danger of what Gaddafi forces were going to do in Benghazi was used as the pretext for military involvement. We then bombed a great deal in Libya. A number of us pointed out in debates in the House at that time that if you simply destroyed the structure of the Libyan state, which is what happened, then you will end up with a series of warring factions. And the spread of arms which were given to the opponents of Gaddafi has then spread into Mali and many other places. So we’ve actually created an arms bazaar of in some cases relatively small scale arms but nevertheless very powerful ones.

'We have got to look again at the whole arms relationship with Saudi Arabia and look again at the foreign policy of Saudi Arabia, sustained by the supply of arms largely, but not exclusively, from Britain'

PO: Let’s move onto Yemen now. Another really topical example of where the Foreign Office – well Philip Hammond – repeatedly misled Parliament as Foreign Secretary. They’ve sort of smuggled out an acknowledgement that they’d given Parliament false information. Is that enough?

JC: No, it’s not enough. I mean [former and current shadow foreign secretaries] Hilary Benn and Emily Thornberry have both made this very, very clear on behalf of our front bench that we are supplying arms to Saudi Arabia and technical support of a significant nature, which is being used in Yemen at the present time. There’s a very large amount of documentary evidence on all of this. And we have got to look again at the whole arms relationship with Saudi Arabia and look again at the foreign policy of Saudi Arabia, sustained by the supply of arms largely, but not exclusively, from Britain which is used – as I said earlier – both in Bahrain and in Yemen. Bahrain has now had significant Saudi involvement for quite a long time to prop up the regime there.

PO: You think it is satisfactory to just put out through a parliamentary answer – a set-up parliamentary answer at that – a correction to a series of mistakes? What would you like to see?

JC: No, I would like to see the [Ministry of] Defence and particularly the Foreign Office called to the House. It is going to have to be in September to explain exactly what the situation is there and I will be discussing that with our foreign affairs and defence teams.

PO: When did you last have a holiday, Jeremy?

JC: Um, year before last.

PO: You don’t have holidays?

JC: I do have occasional holidays. I had four days in Malta over Christmas and I was condemned for indolent behaviour staying at a golfing hotel. The golf course was actually a miniature golf course on the roof of the kitchen. I don’t play golf anyway, not of any sort. And then we were due to go for three days to South Devon over Easter. We ended up going for one day because of the crisis in the steel industry. So we had a full day in Exmouth.

PO: And this summer?

JC: No, this summer there might be the odd day here and there but that’s all. But listen, most people can’t afford a holiday. Most people don’t get breaks other than staying at home and going to the park and stuff. I tell you what, yesterday I had half a day off. I went to Finsbury Park. And we had a good run, we had breakfast in the cafe and chatted to lots of local people who were having a day out with their kids in the park. It was lovely. Not very exotic.

PO: No, no, no, Finsbury Park is – anyway – depends on your perspective. Can I just clear one thing up on an earlier answer. The families of the Iraq war victims are talking about taking a private prosecution I believe towards Tony Blair. What’s your attitude towards that?

JC: I had heard they were considering this. Indeed I spoke to some of them on the day of the Chilcot publication, where clearly Chilcot publication day was a difficult day for them. I understand that they’re preparing that. I think it ought to be on the whole decision-making process. It wasn’t one person. There’s a whole series of stuff that Chilcot has exposed and I think they might end up changing the course of history in the way in which major political decisions are made in this country. We are moving away from executive power towards parliamentary power towards popular involvement. That’s got to be a good thing.

PO: You can’t take private prosecution of a process though.

JC: No, it would have to be an individual. They’d have to name individuals. You can’t discuss a process but the reality is that in the long run it is a process, which is going to have to be examined. Which is why I take it back to the issue of a War Powers Act.

'If we want to live in a world of peace, live in a world of justice towards human rights then there has to be a foreign policy that reflects that. That is where I’m at'

DH: How are you going to turn around what has now become British foreign policy and that is a policy of selling arms, a default position of supporting dictatorships, of ignoring human rights, of dealing with [Egyptian President] Sisi after he’s massacred thousands of Egyptians, of business as usual in the Middle East? How are you going to turn that round and what is your response to the cynics that say "Don’t be so silly, it’s a hundred thousand manufacturing jobs in Lancashire"?

JC: You have to have a process first of all of challenging the human rights record seriously of those countries involved. We are incredibly selective on human rights issues in Britain. We sign up of course to the Universal Declaration, the European Convention and we do have the Arms Export Control Committee in Parliament but we are actually very selective about this and we’ve done precious little about Saudi Arabia for a very long time. I am one of the few MPs who has regularly raised the issue of Saudi Arabia and its human rights in Parliament along with Indonesia and a number of other countries.

And so I want to say that first of all we are serious about human rights, we are serious about having a human rights advisor. In British embassies around the world this government has taken them out and replaced them with trade investment advisors.

Secondly, that we push for the enforcement where there are human rights clauses in European trade agreements with different countries and there is always a human rights clause in an EU trade agreement. Now post-EU-Brexit it may well be that we’re into different trade agreements with countries around the world. There has to be, as far as I’m concerned, a very tough human rights clause within that.

So that sets the narrative and sets the benchmark. The next one is on arms exports. Because if we export arms and they are then used in Bahrain to kill people on the streets of Bahrain well who’s guilty? Who is responsible? Are we not responsible? We knowingly sold those arms knowing they were going to be used in Bahrain. So is it possible to change those things? Yes. But is it going to take a long time, is it not going to be easy. It’s not going to be easy. It is going to be very hard to do it but I do think we have to move in that direction.

If we want to live in a world of peace, live in a world of justice towards human rights then there has to be a foreign policy that reflects that. That is where I’m at.

PO: I’m a student of history and I’ve studied your candidacy for the Labour Party and your leadership of the party. There’s a wonderful book by one of my intellectual heroes AJP Taylor called The Trouble Makers.

JC: I have it, yes,

PO: You have it? Well you’ll know what I’m talking about – the radical tradition in English or British foreign policy. And it goes back to Tom Paine, William Cobbett, John Bright, Samuel Morley, Ramsay MacDonald during the outbreak of World War One…

JC: MacDonald up until the end of the first Labour government.

PO: Do you see yourself as a figure in that tradition?

JC: Well, you don’t want to put yourself into history too quickly. But I do draw inspiration from those people that stood up in very difficult circumstances. I think Tom Paine is a fascinating person. Where did he get his ideas from? He grew up in a very traditional rural community. He was a religious person, as indeed anyone getting on intellectually in those days would have had to have had a relationship with the Church. He developed an incredibly radical book which was then immediately condemned by Mary Wollstonecraft because it didn’t deal with the question of women. It then inspired her to write her Treatise on the Rights of Women.

So I absolutely admire those people. The other one that you didn’t mention is William Godwin, who was a contemporary in many ways of them and he faced charges of treason for supporting the French Revolution. So it is only 200 years ago at the early part of the 19th century that Britain was prosecuting people for treason for supporting a process – doing nothing more than politically supporting a process happening in France.

I think it is amazing the way they stood up on it and it’s those ideas which stand the test of time. We had a very interesting discussion with [Nigerian poet and novelist] Ben Okri two weeks ago at the Royal Festival Hall on the influence of literature on politics and politics on literature and the way in which in reality the long-term political changes often come from quite profound and very brave individuals. Like Paine, like Shelley, like Godwin and many, many others like [Richard] Cobden, Bright in a different political direction.

PO: Actually Taylor says…

JC: Taylor would have all those…

PO: He says in the introduction of his book that the radicals, and I am lumping you with them, are always out of power at the time and proved right and indeed become official policy about 25 years later on…

JC: We’re just speeding up the process here.

'Listen, there will be no peace in the Middle East until you get justice and therefore I do support the recognition of Palestine'

PO: That said, here you are – a figure with unblemished integrity and a track record of remarkable intellectual and moral consistency on these issues. You’ve become Labour leader. I’ve been a bit disappointed you haven’t been radical enough for me in many ways, rather than the other way around. Do you share that?

JC: I look back on the past 10 months – and it is only 10 months – it has been very highly pressurised period. There is an awful lot of things to do day to day. Appointing people and all those kinds and dealing with the day-to-day in Parliament.

I have to ensure that I, me, my team actually have the space to think on the wider perspective and the longer perspective. Have we been as effective with that as we would want to be? Maybe we’ve got to work harder on that and I’m working hard on the direction of foreign policy, direction of environment policy, the direction of social policy.

Remember we were starting from absolute scratch 10 months ago and I want to see that grown. I do take inspiration from a lot of people. I, obviously from a lifetime of political activity, have met a lot of very interesting, very well informed, very principled people. It is very important that if you are a political party leader you are not just a manager of that party. Management is one part of it but it’s not the whole story. The whole story is about reaching out with that perspective and so I want to develop the foreign policy perspective a great deal more. You know of my interest and knowledge on these issues and that’s why I just gave you an idea of that surrounding human rights.

DH: Do you think you’ve got the time to do all of this? Theresa May could be tempted to call an election in the spring.

JC: Well she might, the new prime minister. She’s got a constitutional issue to get round the statute of limitation on Parliament. You know, the Fixed-term Parliaments act. She could get round that by either encouraging Parliament to vote for a dissolution, which I suppose they might. Or a repeal of that act.

But if an election comes we’re ready for it and we will take it on. Politics is a fast-moving thing. People out there that want somewhere to live, that want their kids to get a school that they can rely on and all of these issues – housing issues, job issues, job security issues - are all needing an election. So we are ready for it.

DH: And on Palestine. You were, are, a massive champion on Palestine. In opposition you’ve been silent on Palestine.

JC: Listen, there will be no peace in the Middle East until you get justice and therefore I do support the recognition of Palestine, which I’ve done. I do want to see that happen. I do want to see an end to the siege of Gaza. I’ve made my position very, very clear on settlements and Israeli expansion.

PO: Is there any more you can do as leader of the opposition though? I haven’t heard you very loudly on the subject. I haven’t heard you challenge British government policy on the subject.

JC: I will be developing this foreign policy. We have a change now in our foreign affairs team as you’ve probably noticed and I think you’ll see more on this from me.

PO: Have you been restricted in what you’ve been able to do in foreign affairs up until the appointment of Emily Thornberry?

JC: Well I disagree with her on Syria. That was very obvious. And the Syria vote was quite a seminal turning point in Parliament in that eventually the majority of the parliamentary party and the shadow cabinet came with me in opposing the bombing. But it was in the midst of the most public possible internal party argument and debate. We’ve now moved on from that.

I will continue to assert my position on that and I will be developing foreign policy a great deal and my views and determination to promote a peace settlement in the Middle East, which obviously has to involve recognition of Palestine as something that is very important to me.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.