'Migrants don't exist': Morocco struggles with migration issues despite reforms

OUJDA, Morocco – A failed attempt to reach Spanish territory from this border town left Mamadou Sidy Diallo in the clutches of traffickers who tortured him and left him for dead on a trash pile.

"Four days of sexual, physical, mental violence. They tortured us to the point of death," said Diallo. "It's a miracle that I'm still breathing."

The 25-year-old Guinean hadn’t planned to be one of the thousands of migrants from sub-Saharan Africa desperate to reach European soil.

After studying in Morocco, he was preparing to head home to Guinea and launch a business. But at the last minute, he decided to join a friend trying to reach the Spanish territory of Melilla, which is situated behind six-metre-high fences on North Africa's Mediterranean coast.

Four days of sexual, physical, mental violence. They tortured us to the point of death. It's a miracle that I’m still breathing

- Mamadou Sidy Diallo, 25, from Guinea

Instead, they were seized by smugglers, who demanded thousands of euros to cross, their plight echoing thousands of other migrants caught up in dangerous situations in Morocco despite recent reforms.

The reforms, launched in 2014 and largely funded by the EU, were intended to encourage migrants to stay in Morocco rather than attempt the perilous journey to Europe.

In 2015, more than 16,000 migrants were allowed to stay in Morocco with year-long renewable residency permits.

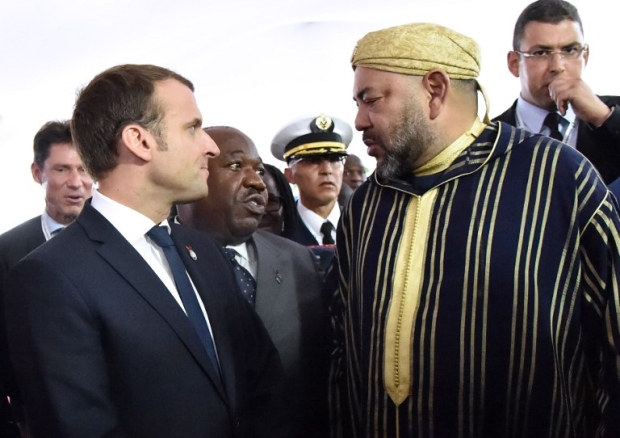

By 2016, King Mohammed VI said the country had "an authentic solidarity policy to welcome sub-Saharan migrants ... which protects their rights and preserves their dignity". The country's efforts have been praised by EU officials.

But the new policies, say aid workers, doctors and advocates, have also created a host of fresh problems for migrants and left them susceptible to dangerous conditions that may only inspire them to try even harder for Europe.

While the European Union praises Morocco for its efforts, migrant advocates say the government is only projecting its image of having solved the migration challenge and hiding serious problems that persist.

Azarias Lumbela, a former student from Mozambique who now coordinates the International Mutual Aid Committee in Oujda, said it appeared that the whole point of reforms was to make it seem as though the migration problem had simply gone away.

Meanwhile, migrants like Diallo - one of 22,900 migrants who tried to enter Spain from North Africa last year - just keep coming.

Keeping up appearances

In an effort to improve relations with both the European Union and with other African countries, Morocco launched a package of reforms in 2014 aimed at reducing the flow of migrants from sub-Saharan countries into Europe.

Morocco's relatively stable politics and economy provide an opportunity to build its prestige and become a leading nation on the African continent. The kingdom also needs good relations with Europe because so many Moroccans live there, and because it depends heavily on European tourism and trade – particularly agricultural products.

Morocco regards Western Sahara as historically part of its own territory and controls about two-thirds of it. However, the United Nations and the African Union support the right to self-determination. The issue has not been resolved, but last year Morocco was able to rejoin the Africa Union after a 33-year absence.

At issue is how many of those migrants who are apprehended in Europe may end up in Morocco permanently, and how many Morocco might be forced to send back to other African countries

The country also agreed in 2013 on a Mobility Partnership with the EU that would not only regulate the legal movement of Moroccans to Europe but also establish policies regarding those who use Morocco as a transit point for reaching Europe. The EU pledged hundreds of millions of euros in assistance.

However, Morocco and the EU have yet to reach an agreement on those who transited Morocco. The EU is pressing for them to be returned to the country from which they arrived; Morocco objects to readmitting people who only transited its territory.

A law was passed in 2015 allowing some migrants who fit specific criteria to register for year-long renewable residency permits. Applicants had to prove they had been in Morocco at least five years, or present a minimum two-year work contract. More than 16,000 qualified, slightly less than half the estimated number of migrants in the country at the time.

While residency might seem like a dream outcome for migrants fleeing their countries, the reality of the entire package of reforms has played out much differently on the ground, especially for those who land in Oujda.

Transit hub

Located on the Algerian border, the city is a major transit hub for migrants from countries such as Cameroon, Nigeria, Guinea, Mali and the Central African Republic.

Hassane Ammari, a volunteer for the Moroccan Association for Human Rights (AMDH), said a steady stream of migrants trickles into the city every day. Most want to go to Europe, even if it takes years’ worth of saving money and multiple attempted crossings.

While Morocco's Western Mediterranean sea route saw triple the number of illegal border crossings in 2017 compared with the previous year, there also has been a drastic increase in the number of crossings on land into the Spanish territories of Melilla and Ceuta. Local news reports said a passenger ship found the bodies of 20 migrants on 3 February near Melilla. They apparently drowned while trying to reach Spain.

Before the reforms, migrants lived in tent camps on the outskirts of the city. They were subject to police violence and exposure-related maladies like pneumonia and open-wound infections, according to Doctors Without Borders (MSF) reports.Dr Tarik Oufkir, a former MSF team member who now heads local healthcare consulting organisation Maroc Solidarite Medico-Sociale (MS.2), said MSF used to treat migrants on the spot.

But these days, MS.2 provides only consultations and prescription co-pays for migrants. Part of the reason is that the tent camps are no longer there.

Shortly after the 2014 reform process started, the Interior Ministry ordered the local police to dismantle them.

"Now you don't see migrants anymore," said Lumbela, the aid organisation coordinator in Oujda. "Everyone knew where they were, and it wasn't good for Morocco's image."

Migrants were free to come and go from the camps, but few have any option now but to take shelter in houses and apartment complexes controlled by the traffickers.

Now you don't see migrants anymore. Everyone knew where they were, and it wasn’t good for Morocco’s image

- Azaria Lumbela, coordinator for the International Mutual Aid Committee

New arrivals are forced to pay 50 euros ($61) for entry and then compounded rent, about $123 a night to start, for a spot to sleep on the floor of a room packed with 15-20 other migrants, said Hassane Ammari, a volunteer for the Moroccan Association for Human Rights (AMDH).

With costs so steep, many migrants find themselves asking relatives from back home to send money, or are forced to find small jobs on the black market. If they can’t afford it, they are then compelled to work for traffickers, including women who are at risk of being forced into prostitution.

And traffickers often use violence to make migrants pay for their services, according to the World Bank. Traffickers use physical and verbal abuse, and threats to the migrant’s family to make sure the migrants are compliant.

Living in crowded and unsanitary living conditions, migrants are at increased risk of respiratory and gastrointestinal infections, and migrant women are treated for sexually transmitted diseases at higher rates than the local population.

But when migrants seek medical care, they face the same problems that confront Moroccans – overcrowded and unhygienic public institutions.

'My civic duty'

On the night traffickers tortured Diallo, the 25-year-old Guinean who tried to reach Melilla, they tied his legs so tightly that they cut off his circulation. The smugglers then left him and his friend in a ditch.

Diallo was found by other migrants, but it was too late to save his friend who died.

When Diallo arrived, he was given a plastic mattress with no bedding and left to fend for himself. For three weeks he wasn't given the chance to bathe.

As local organisations scrambled to find him a safe home, Diallo used his time in the hospital to write down his experiences, not only to process what happened to him but to let the world know of the dangers facing migrants in Morocco.

He particularly wanted to warn other Guineans who wanted to migrate to Europe about the dangers that could await them.

"It's time I do my civic duty," he said.

Three months later, he returned home to his family, but whether those determined to leave will heed his advice it's hard to say.

The EU and the Moroccan government did not respond to requests for comment.

Gillian Coyne spent several months in Morocco on an SIT study abroad program and produced this story in association with Round Earth Media (www.roundearthmedia.org)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.