'It’s still a nightmare': Iraqi refugees in US refuse to lose sight of home

Twenty years ago, the US invaded Iraq, changing the lives of millions forever and killing hundreds of thousands of civilians in the war and its aftermath.

According to Brown University's Costs of War, 9.2 million Iraqis are internally displaced or refugees abroad - the 2003 US invasion displaced approximately one in 25 Iraqis from their homes.

One Iraqi woman would take her family and leave for the US in 2019, leaving everything she ever knew behind her.

One Iraqi man would arrive in the US with his family just days after the 9/11 attacks, as his father wanted to start a new life after facing political persecution.

Another woman, who is Iraqi American and was once ashamed to be of Iraqi heritage, would go back to her father’s homeland for four months to see the devastation the war has left behind.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Two of them left Iraq as refugees, and one of them went back to find her roots. All three of them would find themselves in the US, yearning for a better future.

Here are their stories.

Leaving Iraq for a different home

Before the US invaded Iraq, Shaymaa Khalil lived a simple life. Born in Babil Governorate in 1984, her family moved to Baghdad when she was five. As she grew older, she enjoyed walking to school and staying out late without any fear. She enjoyed going to the crowded markets with her family and shopping to her heart’s content. She enjoyed not having to worry.

But in March 2003, all of that changed. She remembers vividly the US Army roaming Baghdad's streets in massive vehicles. People would watch the soldiers loitering on the streets from their windows. Khalil said it felt like a nightmare that she needed to wake up from.

“But I woke up and it’s still a nightmare,” she told Middle East Eye.

On 13 December 2003, Saddam Hussein, who served as Iraq’s president, was captured. His government had controlled the country for 24 years. When he was overthrown, Khalil breathed a sigh of relief.

“There was no more Saddam Hussein regime. We thought better things would come. We thought maybe we will have a better life and see improvement and see Iraq live. We expected a beautiful life, something different from Saddam’s regime. But that did not happen,” Khalil said.

“The US didn’t come to serve people or improve my country or for justice. They came for their own benefits.”

Her hope turned to fear, as he would often hear about killings on the street. She explained how every Saturday and Sunday, the markets would be bustling with people, but those very markets became prime bombing targets.

On 5 March 2007, a car bomb detonated on Al-Mutanabbi Street in Baghdad, ripping through the heart of the centuries-old literary and intellectual community centre. More than 30 people were killed and over 100 were wounded.

Khalil knew of a shop vendor from a very old cafe that sold traditional Iraqi tea and coffee. The owner of that cafe had opened his business over 30 years ago. She remembers how he had four sons - and on that day, all four of them died.

On 3 July 2016, a suicide bomber detonated an explosives-rigged vehicle in Baghdad's Karrada district during the holy month of Ramadan. Fires ravaged shops and there was chaos. Nearly 300 people were killed and 200 were injured. Khalil remembers feeling terrified when she saw it on the news.

She says one of the hardest parts of living in Iraq during the war was keeping her children safe. Her top priority was her two kids and she would do anything to protect them, such as on 19 August 2009, when she witnessed a bomb in front of her eyes.

'There’s no reason that gave the US the right to invade my country'

- Shaimaa Khalil, refugee

Khalil was taking her son to kindergarten and all of a sudden there was a big explosion outside the foreign ministry's offices. She remembers covering her son to protect him and seeing glass shattering into tiny pieces.

She ended up with minor injuries and they both made it out alive, but not everyone was as lucky. Nearly 58 people were killed in that explosion.

In March 2019, Khalill and her family made the journey to the US as refugees. They live in Minnesota, and while their lives have changed drastically, Khalil can’t forget the home she left behind.

She can’t forget her big house in Baghdad that was surrounded by palm trees or how she’d sit in the garden looking at those trees under the sky, which she emphasised was always “pure and blue”. She can’t forget masgouf, a dish consisting of grilled carp fish, considered the national dish of Iraq.

In Minnesota, no matter how many times she has tried to make it or eat it at a restaurant, it just doesn’t taste the same.

Khalil believes the war was unjustified and blames the US government for not maintaining peace.

“There is no good war and bad war. War is bad in all aspects. And it's affecting generations. There are bad consequences of war. There is no good thing that will come from war. I don't believe when some people say war can sometimes solve issues. I don't believe in this,” she said.

“There’s no reason that gave the US the right to invade my country,” she said.

Khalil spent the first eight months in the US trying to figure out who she would be in her new country. No one knew her, she said. How would she find work? How will she find a community? How will she establish a good life for her kids? How will she maintain good mental health? How will she preserve her culture?

“My brain was full of so many questions and no answers. Those eight months were a heavy burden on my shoulders. Every day was a challenge," she said.

She began working for the Iraqi and American Reconciliation Project (IARP), a nonprofit in Minneapolis that aims to build bridges of communication and understanding between Iraqis and Americans.

It was there that she found her community. It was there that she found the young, Leila Hussein.

Finding roots in Iraq

Hussein was five years old on 11 September 2001 and seven when the US invaded Iraq. As a young girl born in the US to a Muslim-Iraqi father and a Swedish-Norwegian mother who is Christian, Hussein felt ashamed of her identity.

It got to the point that she wanted to legally change her name. But it was her mother who wouldn’t let her. And today, she is glad her mother was firm. It took her a long time to take pride in her name, Leila, which means night in Arabic, and Hussein, who was the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad.

It wasn’t until she went to college that she learned about “what was actually happening in the war”. She met people from the Middle East, studied Arabic and began working with refugees. Soon she realised that she wanted to reconnect with her roots. The only connection she had to Iraq was her father and grandparents.

Hussein’s grandparents still live in Baghdad. She remembers asking them about their experiences, but they would always shut down. She believes it’s because they had a deep fear that she’d never be able to truly understand what they suffered. That, and they were paranoid even mentioning Saddam’s name. They felt that someone was always listening and you could trust no one.

“That’s what Saddam Hussein’s regime did to them. It really instilled a lot of fear in them. My grandpa was always a very political man and he has strong opinions,” Hussein said. “But he would never share them because he was scared of the consequences of being an outspoken person - of speaking against the war and against the regime.”

In 2019, as part of a programme for teaching English, Hussein travelled to Najaf, a city about 160 km south of Baghdad and one of the holiest cities for Shias. It was those four months she spent there that transformed her life.

Hussein landed in the war-torn country expecting hostility as an American. But what she experienced what the complete opposite.

'Iraqis didn’t associate me with the atrocities of my government. They saw me as a human'

- Leila Hussein, Iraqi American

During her first week there, one of her neighbours invited Hussein to her home and hosted a dinner. The woman had lost one of her legs during the war when her home was bombed.

When Hussein asked her more about the war, she didn’t want to talk about it. Instead, she wanted to get to know Hussein.

“She had every right to hold that resentment over Americans, over me. But Iraqis see the difference between the government and the people. They didn’t associate me with the atrocities of my government. They saw me as a human,” she said.

“They didn’t see me as a half-mixed person. They saw me as an Iraqi.”

Hussein recalled how they’d often tell her “welcome home” and tell her “You are Iraqi and this is your home.” Coming from divorced parents, Hussein wasn’t connected to her cultural identity, but that changed once she heard those words and experienced her father’s country.

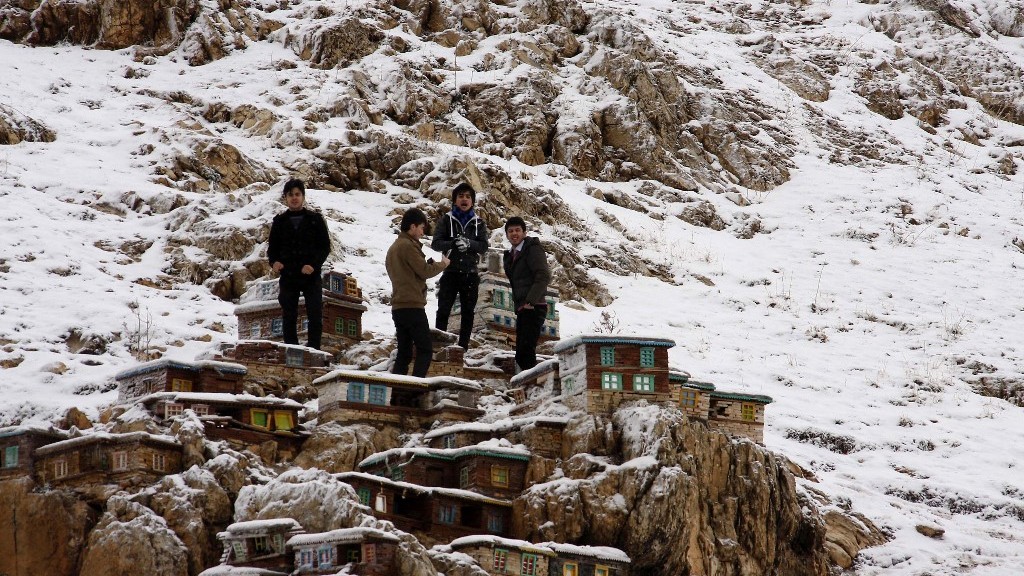

Every Friday, she’d go on a field trip with her high school students. They’d often visit a historical landmark. Every time she saw those sites, Hussein would get a little sad. She would think about why she never heard of these places before, and how much people were missing not knowing about them. She believes it’s something the media should show.

Every time she’d search for "Iraq" on film-streaming apps, she would be met with documentaries about war, violence and terrorism. But that’s all wrong, she said. There are marshes in the south and mountains in the north. People ski in Iraq - it is not just a barren desert, Hussein explained passionately.

“The media played a huge role in conjuring this image of Iraq as barbaric, uncivilized, and in need of saving. It facilitated the white saviour complex,” she said.

So what gives her hope?

“The youth of Iraq gives me hope,” she said.

Hussein explained that when she was in Iraq, she asked all of her students if they were planning on staying there and where they say their future. To her surprise, most of them said they wanted to stay in their country and be a part of the rebuilding of Iraq. They wanted to repair the infrastructure and bring tourism back.

“Even though Iraq is so broken as a consequence of the war, it really is so incredible that they still see so much hope in Iraq's future,” she said. “And that makes me very hopeful.”

Alongside her work with refugees in Minneapolis, Hussein is also a board member of the Iraqi and American Reconciliation Project. To her, it’s always about staying connected to her roots.

About 1123 km away in Detroit, a young man named Ahmad Alkaabi is staying connected to his.

From Iraq to the US

It was on 27 September 2001, when Alkaabi and his family landed on American soil as refugees. He was six years old and his family was fleeing political persecution in Iraq. His father’s name was on a list of people slated for interrogation for political activities. If they had stayed, he could have been killed. So Alkaabi’s father packed his bag, grabbed his family and they left home.

Arriving just after 9/11 didn’t make it easy for his family. At a young age though, Alkaabi’s mother tried to hide how bad it really was. He recalled one time when they first arrived in Connecticut, they decided to go to the park and check out the beach.

They were soon met by police officers there. At the time, Alkaabi didn’t understand what was happening. But he’d later come to learn that someone nearby called the police because they felt they were witnessing “suspicious activity”.

“Our mere existence was suspicious activity,” Alkaabi said. “There was just a lot of fear and tension around that time.”

So, they left Connecticut and settled in Detroit, Michigan, where there was an established Arab and Muslim community. They wanted to be in a safe place that would feel a bit like home, and it did.

In 2017, Alkaabi, along with others, established the Iraqi American Union at the campus of the University of Michigan-Dearborn. It became a safe space where people could come together and collaborate, organise, and support each other and their rich culture.

The organisation is now on four different campuses. Once Alkaabi graduated from college, he founded the Iraqi American Foundation, of which he is currently the president.

Since his arrival in the US, he has gone back to visit his home three times. Once in 2009, though he doesn’t remember much of that trip, then in 2013, and then again in 2020, right before the Covid pandemic. His family is from Amarah, a city in southern Iraq, located about 50 km from the border with Iran.

He describes his neighbourhood as simple yet beautiful and having colourful gates and walls peppered with grape leaves, with palm trees overshadowing the street and providing much-needed shade in a hot country. When he went back to visit at a young age, he remembers asking, “Man, this is it?”

He said he was young when he fled Iraq, so all that he knew about the country was what everyone had told him, which was mostly about how beautiful it was. But when he visited in 2009, he couldn’t find the beautiful things they spoke about, as the war had changed things and it was a city that didn’t get as many resources as the bigger ones.

'You can't have prolonged invasions and wars to make this happen. That's not how democracy comes about'

- Ahmad Alkaabi, refugee

But still, he enjoyed his time there and it helped that his grandparents - who now reside in Australia - and the rest of his family all coordinated a visit at the same time, which is hard to do as his family is scattered all over the globe.

“Unfortunately though, that's the reality of a lot of Iraqis after the war. The destination didn’t matter, surviving was the ultimate concern,” he said.

Alkaabi explained that most people who left Iraq, left with the intention of coming back, but that never happened.

“The idea for many Iraqis was ‘We're staying here because we're fleeing political persecution and the gruesome realities of war, but once it’s over we'll be back’. But that never happened. And I know a lot of families who thought that way,” he said.

The problem is that these people left their homes in a state of stagnation and limbo, he said.

“Their idea for many wasn’t to come here as immigrants for the business and new lifestyle, like other waves of immigrants,” he said. “They were coming here because they were forced and uprooted because of a war.”

Ultimately, though, does he believe the war was justified? No, he said, but the answer isn’t that simple. Iraqis wanted to get rid of a dictator, he explained. But they did not expect that leading to a prolonged and bloody invasion.

“It was not a justified war. It was never about democracy," he said. "As Americans, we love the words democracy and freedom. But war is not the proper means of achieving it. You can't have prolonged military invasions and proxy wars to make it a reality. That's not how democratic societies are formed. Democracy is fuelled by the people, as Americans, we should be the first to know that.”

Twenty years since the US invaded Iraq, Alkaabi remains passionate as ever in making sure no one forgets the true realities of the war. Hussein is making sure she stays connected to her roots. And Khalil is making sure generations to come know where their home is. For them, it is Iraq. It will always be Iraq.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.