One year after January massacre, where is Charlie?

PARIS – An elderly woman with brown hair and a red coat stands back from the building with tears in her eyes. We are in Nicolas-Appert Street in front of the former offices of the satirical magazine, Charlie Hebdo.

A year ago, Chérif and Said Kouachi killed 11 people here, including most of the editorial staff, including cartoonist and editor-in-chief, Stephane Charbonnier, known as Charb, and the policeman in charge of security.

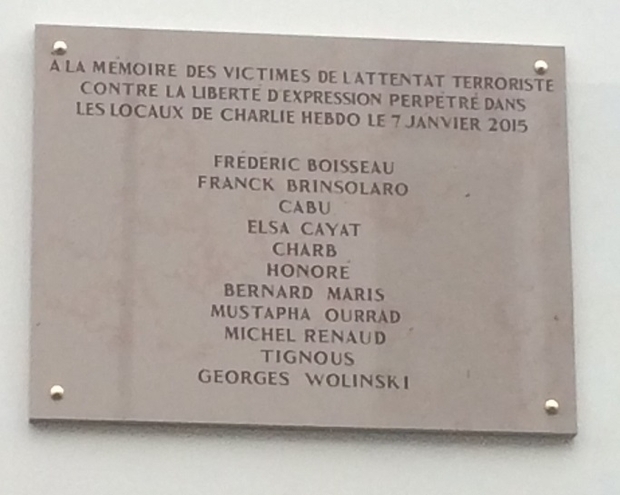

Today, a few people and journalists stand in front of a commemorative plaque, paying tribute to the victims of the “terrorist attack against freedom of expression”, as the marble sign reads. Only a couple of flowers lie underneath.

The famous plaque had to be replaced quickly this week after a typo in the name of Georges Wolinksi, better known simply as Wolinski, the cartoonist, was discovered.

A young woman drove by on her scooter and looked on. “Simply continuing to live,” she said, and drove on.

‘They were friends’

A bit further away, close to the Bataclan concert hall, a retired lady calls for her dog, Lola, who is having fun in one of the parks of the Boulevard Richard-Lenoir. She said she feels these tributes to Charlie Hebdo have arrived too late.

“This typo in Wolinski’s name is pathetic. Really!” said the woman in her sixties. “And all of this during the state of emergency, it is dishonest.”

Despite the arrival of heads of state to Paris for the march last January, even then, she said, she and her friends questioned whether they should go. This year, most people who actually gathered in January didn’t come to commemoration events, held this past Sunday, at the Place de la République.

Despite her criticism of the state of emergency and the botched plaque, the woman, who used to work in the media, said that she was personally “deeply moved” and considered the magazine staff as friends.

A two-minute walk away, at the doors of the Bataclan, there is no trace of the tributes for the 89 victims killed here on 13 November by three armed men which was claimed by Islamic State.

They are, instead, across the street at the Boulevard Richard Lenoir, next to the Paris Town Hall, where dozens of men and women read notes, light candles and take photos.

“That is the least we can do,” Marc, a doctor, told MEE, referring to the tributes for the anniversary of the massacres at Charlie Hebdo and the kosher market in Porte de Vincennes two days later when five people, including the shooter, Amedy Coulibaly, were killed.

“We speak way too much about the killers, but not enough about the victims,” he said.

To him, it is no wonder that, one year after the Kouachi brothers and Coulibaly’s disastrous expeditions, a certain unease remains for these commemorations. “There is no more unity,” he said. “The mood is too bad for that.”

Lost meaning?

A lack of unity felt among the French is visible at the Place de la République. Usually the go-to place for popular Parisian demonstrations, it has been a centre of rallying and commemoration, especially since last January and also after the attacks in November.

But now, the anonymous tributes remaining there leave a bitter taste, said some onlookers, especially since they are side by side with around 50 tents meant to express solidarity with refugees whose cause remains unsolved. After so many events and causes this year, there is a sense of uselessness.

“Honestly, I do not know,” said Carine, a teacher, when asked what she thinks about this week’s tributes. “We can try to send political messages on the anniversary date, but there is no point.

“They won’t come back. It only rubs salt in the wounds of the families and the victims,” she said. “I am not Charlie, but what happened is horrible. At the beginning, I liked their cartoons, but I did not like when they started drawing the Prophet, and picking on Muslims.”

She stares at the flowers and the anonymous notes.

“I can’t understand young people who go there [fighting in Syria with the Islamic State]. But that some celebrities like Johnny Hallyday [a French singer] say that they would go to fight [the IS] if they could, it is truly rubbish,” she said bitterly.

The 58-year-old, who comes from Pau in southern France, is also wary of politics and the government: “With the state of emergency, they were already restraining our liberties. There were police blunders and now, they want to give full power to the police.”

Since January, there was November

“These commemorations take place in such a context that people are not interested in them,” said Philippe Marlière, a political scientist at the University College of London.

“Since January 2015, there has been November 2015,” he said.

While the Charlie Hebdo attacks had specific targets, the randomness of the November attack left people feeling more vulnerable, he explained.

“An attack even more bloody and that affected absolutely everyone,” he said. “The fight for Charlie Hebdo is no longer a priority in people’s minds.”

Attempting to bring to life events that happened spontaneously last year, including a national demonstration of thousands in the street of Paris to prove national unity after the bloody attacks, the commemorations ring hollow to Marlière.

“It was then a quite positive message of hope and there was a will not to name a scapegoat and to resist terrorism,” he said. “Unfortunately, scapegoats have been quickly blamed.”

Freedom of expression, vivre-ensemble – a term which French President Francois Hollande used repeatedly after the attacks, which means co-existence - and free criticism of everything – are the public battles that united people after the Charlie attacks. But where is that unity now?

“There is no unity around Charlie because people are divided on different levels,” Marlière said. “Everyone is against this act of barbarism, but not everyone agrees with the messages conveyed by Charlie.”

There have always been divisions around Charlie Hebdo, and there will always be. However, these commemorations illustrate a real malaise in French society, at a time when the vivre-ensemble is threatened.

“There is a very authoritarian trend that stirs up fear of attacks, but also fear of others,” said Marlière. “There were not many reactions to the events in Ajaccio [a mosque that was set on fire in Corsica last month]. Politicians allow themselves [to make] racist comments, the French president should not allow that. Yes, we must speak about dangers, but we also must mitigate them.”

“The plan to strip off people with double nationalities of their French nationality only happened because it seemed to be approved by the public opinion. But people are realising that there is something wrong,” he explained.

“This will be useless. They are now speaking of rendering people stateless. The government seems to say, ‘We see a racist public so we will do racist policies.' It is very dangerous and can only feed the Front National.”

To Philippe Marlière, “the true commemoration would be to restore people’s confidence. The civil power, politicians and media must promote social harmony."

Translation from French (original) by Valentine Maury.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.