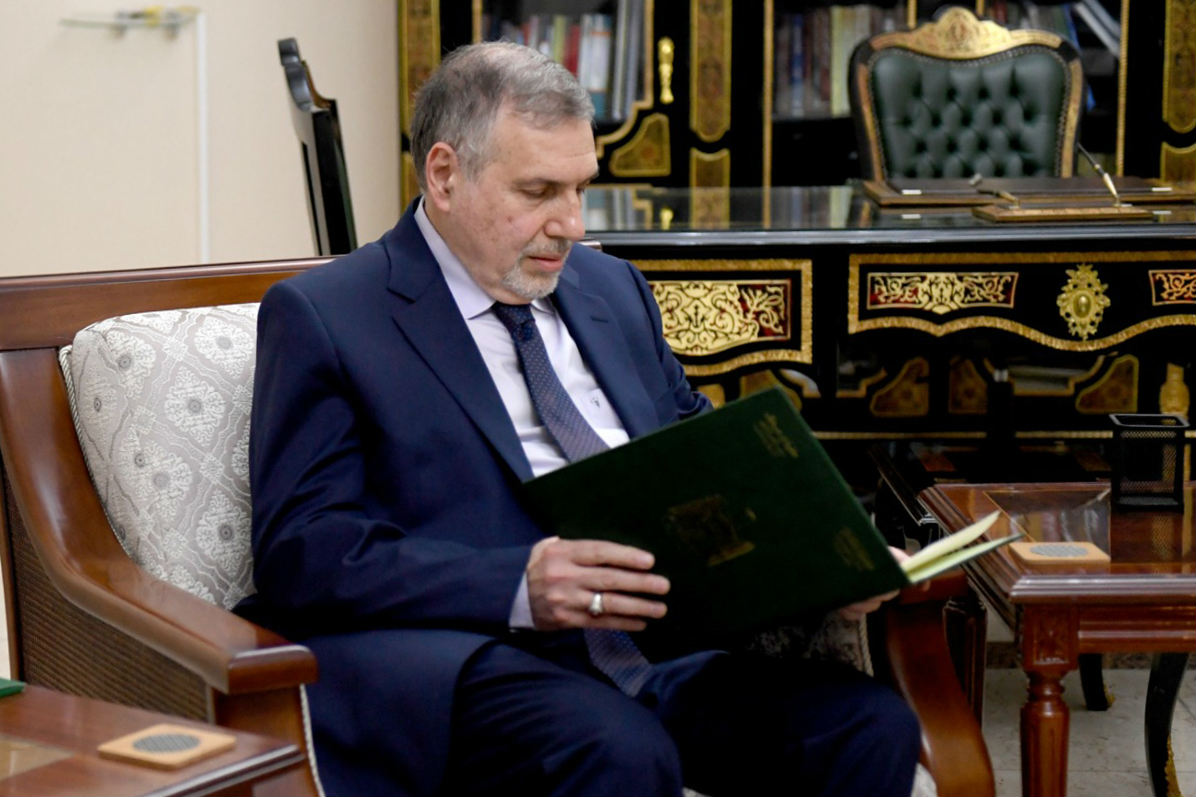

Organised chaos: How Allawi's bid to become Iraqi prime minister fell apart

For weeks Mohammed Tawfiq Allawi, the man charged with becoming Iraq’s next prime minister, believed the support of Muqtada al-Sadr was his greatest asset.

He never imagined the influential cleric would instead end his political career.

Allawi, a veteran politician who has operated in Iraq since 2003, was last month handed a task of extreme importance: form a new government and lead Iraq out of the tumult it is suffering through.

For five months, protests against corruption, lack of services and unemployment have sprung up in Baghdad and nine southern provinces, bringing down the previous administration and sparking a ferocious crackdown that has killed over 600.

'We had to teach him a lesson so he learns his real size'

- Shia leader on Sadr

Meanwhile, the US killing of top Iranian general Qassem Soleimani and Iraqi paramilitary leader Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis in Baghdad in January destabilised things only further, with Tehran and Washington at times appearing on the brink of war inside Iraqi territory.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Supporting Allawi was part of an agreement between Iranian-backed Shia armed factions represented by Hadi al-Amiri, leader of the parliamentary Fatah bloc, and Sadr to create a “resistance front” against the United States in the wake of the Baghdad drone strike.

His choice was the culmination of eight weeks of marathon negotiations in the Iranian city of Qom aimed at reconciling and uniting Iraq’s armed factions.

Getting enough votes in parliament to endorse the prime minister-designates’ government was the first real test of the strength and seriousness of the alliance between Sadr and the Shia groups.

That test was failed on 2 March, when Allawi failed to get the required votes in parliament to form his government. Violations by both parties of the terms of the agreement may yet lead to its total collapse.

Part of the establishment

The protesters never accepted Allawi.

Despite operating as an independent, the former communications minister under Nouri al-Maliki was denounced as part of the establishment.

Demonstrators wanted instead someone they deemed truly independent, who could lead a transitional government tasked with preparing for early parliamentary elections.

Sadr, who controls a powerful armed faction, took it upon himself to quash the disquiet of the protest movement, pursuing rejectionists and silencing them through force.

Many demonstrators were killed and wounded in direct armed attacks led by the “Blue Hats”, one of the groups affiliated with Sadr, in Baghdad and Najaf over the weeks Allawi was trying to form his government, security sources and eyewitnesses told Middle East Eye.

Politically, meanwhile, Sadr extended his support of Allawi by sending several threatening messages to the Sunni and Kurdish political forces that were sceptical of the prime minister-designate.

Effectively, that positioned Sadr as Allawi’s most prominent supporter in political and popular circles.

By 23 February, a week before the deadline agreed by partners to vote on Allawi’s government, the ground was paved for Allawi to go to parliament to approve his proposed cabinet. At that point, it appeared he didn’t even need the blessing of prominent Kurdish leader Massoud Barzani, Speaker of Parliament Mohammed al-Halbousi and Maliki, the former prime minister.

However, things abruptly changed, and Allawi’s most prominent Shia, Sunni and Kurdish supporters, other than Sadr, suddenly turned against him, people involved in government-forming negotiations told MEE.

Fireworks on television

That volte-face can be traced to one event: an hour-long interview with Sadr on Iraq’s Al-Sharqiya TV channel.

In the first five minutes of the interview, Sadr introduced himself as the “sponsor” of the political process and the “sergeant” keeping the demonstrators and Shia, Sunni and Kurdish political forces in line. He has a right to “punish” them whenever it is needed, the cleric said.

Later, Sadr said he would throw any politician who refused to vote for Allawi’s government "into the trash", adding that the Kurds and Sunnis – who have so far stayed off the streets - should also demonstrate against their politicians because corruption is not only limited to Shia politicians.

"Many non-Shia politicians are corrupt and they also need to be punished," he said.

Before midnight, most of Sadr's new partners had decided to "teach him a lesson until he knew his real size", a prominent Shia leader told MEE.

Desperately trying to contain the damage of Sadr’s interview, his allies tried to bring forward the session in parliament to vote Allawi’s cabinet in, despite the fact that Allawi hadn’t definitively decided his candidates for six ministries, including the interior and defence.

With Halbousi refusing to hold the session before he and Barzani reached a final agreement with Allawi, Hassan al-Kaabi, a Sadrist and first deputy speaker of parliament, set a date of 27 February for the session.

'What Muqtada al-Sadr said during that interview eliminated any opportunity for Allawi to obtain sufficient votes to endorse his government'

- al-Nassar bloc leader

A lack of quorum scuppered that session however, with voting put back two days under the pretext of providing more time for Allawi to persuade his Sunni and Kurdish opponents to participate in his government.

But the problem that the prime minister-designate was facing was much greater.

"The situation had become more complicated. What Muqtada al-Sadr said during that interview eliminated any opportunity for Allawi to obtain sufficient votes to endorse his government," a prominent leader of al-Nassar bloc, headed by former Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi, told MEE.

“It seemed as if Muqtada had led a conspiracy to bring him down. The Shia forces that initially announced their support for Allawi changed their position. They wanted to break Muqtada’s prestige by preventing the endorsement of the Allawi government.”

On 29 February, the situation worsened still, as the al-Hikma, al-Nasr and Badr blocs, which kept their promise to support Allawi until the last moment, were unable to mobilise more than 100 MPs to hold the session, forcing it to be postponed for several hours.

"It was right to have done this [boycotting the vote] for the benefit of Iraq," said one of the heads of the Shia blocs preventing the MPs from attending the session.

"Sadr spoke with intransigence, telling everyone that he is the guardian of us, that we are part of the herd that follows him, and that we cannot afford to refuse to vote for a government he has chosen. We had to teach him a lesson so he learns his real size.”

Changing the system

In truth, Allawi was making life difficult for himself long before Sadr’s inflammatory interview.

Since 2005, Iraqi political forces have attributed ministries to blocs in proportion to their seats in parliament. The heads of the blocs would each nominate the ministers to occupy the portfolios assigned to them.

When Allawi was tasked with forming a government, however, he announced that he would not choose his ministers according to the quota system and that none of the blocs could nominate his ministers.

The Kurdistan Democratic Party, led by Barzani, and Halbousi’s National Forces Alliance refused to give up these privileges, publically demanding the right to choose their ministers as long as Shia political forces maintain their right to choose the prime minister.

[Allawi's] use of his sons was a mistake, although they are very smart, polite, well-educated and hard workers. But they do not know anything about Iraq and dealt with the situation with a British mentality'

- Thaer al-Faili, Allawi aide

Barzani wanted to keep Fouad Hussein, the current finance minister, and Benkin Rikani, the current minister of construction and housing, as part of the new cabinet, while Halbousi insisted on nominating two ministers as part of the Sunni share.

Allawi refused to countenance the idea until the evening of 25 February, one of Allawi’s team told MEE, so efforts failed to hold a voting session the next day.

Two days later, Ammar al-Hakim, leader of al-Hikma parliamentary bloc, held a lunch banquet that Halbousi, Allawi, Hussein and Faleh al-Fayyad, the head of the National Security Service, called for "in an attempt to break the ice between the three parties and to resolve differences," Fadi al-Shimari, leader of al-Hikma, told MEE.

That Friday meeting reportedly yielded a preliminary agreement with the Kurds to grant them three ministries, in addition to the position of deputy prime minister. Halbousi, it seemed, was not offered similar terms.

"That angered Halbousi, who found out about the matter shortly before Saturday's session,” one of the negotiators told MEE.

Personnel problems

There were also issues in Allawi’s team.

Preparations for the premiership had been ongoing for two months ahead of his nomination, according to several sources, including the formation of a working group that included many businessmen who travel between Baghdad, Beirut and London.

Some of them helped progress Allawi’s negotiations with Sadr through intermediaries, before his name began circulating publicly.

Allawi's team, which also included a number of his old friends, drafted the government’s manifesto and entered into preliminary negotiations with influential Iraqi political figures inside and outside the country, to ensure that they would not put up barriers to his nomination.

The team, however, was shocked to discover that Allawi had decided to dispense with the majority of its members just one day after he was officially asked to form a government, two of Allawi's close associates told MEE.

"In our first meeting with him, one day after the assignment, I found myself sitting with him accompanied by someone I did not know. Not all of [the team] were present, and then I discovered later that only three of us were left with him," one of Allawi’s team members told MEE.

"I don't know if this was a personal decision, or whether it was a response to the request of one of his big backers or what.”

As part of the shake-up, Allawi brought on board his sons Hadi and Haidar, who later played an essential role in managing the affairs of the prime minister-designate during the four weeks allocated to form an administration.

Hadi, Allawi’s eldest son, who works as a lawyer for a major British company based in London, brought with him his friend and former colleague Safwan al-Amin, a British-Iraqi lawyer working in Dubai.

The trio of Hadi, Haider and Safwan quickly took responsibility for everything related to the prime minister-designate.

'He ignored the demonstrators completely and continued to repel some political forces'

- member of Allawi's team

"Hadi and Safwan were the ones who were interviewing the candidates, and negotiated with the political blocs and the ambassadors," a member of Allawi’s team told MEE.

Everyone spoken to by MEE for this story confirmed this.

Although Iraq's president, Barham Salih, sent one of his employees, Ali al-Kinani, to help Allawi manage his office, Amin was the one “who supervised most of the details”.

As for the position of media advisor, Diaa al-Nasiri from the president’s media office was first earmarked - after consultations between one of Allawi’s representatives, Salih’s office and the Iraqi state-owned media network, according to sources.

But after just a day in the job, MEE was told, Nasiri was discarded in favour of Karim Hammadi, a presenter and former director of state-owned Al Iraqiya satellite channel.

Nasiri told MEE, however, that Allawi's team called him and offered a job as a media consultant, but he rejected the offer. He also denied that Salih’s office and the Iraqi media network had anything to do with his nomination.

Hammadi never got the chance to assume his duties. Allawi instead appointed businessman Akram Zangana, despite his media experience being limited to his ownership of the al-Taghair channel, a member of Allawi’s team told MEE.

Hammadi told MEE he never received an official written invitation to take up the position, although Allawi's team met him twice and he heard informally he had been appointed.

Another controversial appointment was the director of Allawi’s office.

Professor Ali al-Yaqoubi, dean of Imam al-Kazim College, was part of Allawi’s preliminary team with the understanding that he would eventually be appointed director of his office.

“But Allawi refused to appoint him just one day after his official designation,” and instead the position was offered to Aref al-Bahash, a businessman and friend of the premier-designate.

"Here the differences began with the Shia blocs, which felt that Allawi turned against all members of the team that brought him to where he is now, and that there is a plan to dominate his office through the inner circle that surrounds him,” Allawi’s team member told MEE.

Yaqoubi declined to comment on these details.

With the 30 days granted to the prime minister-designate to form his government drawing to an end, pressure increased on Allawi politically and popularly, especially “as he ignored the demonstrators completely and continued to repel some political forces”, the team member said.

"Under his feelings of loneliness" Allawi summoned five other friends, four of whom resided in London, to join his team, including Akram al-Hakim, a veteran Iraqi politician and former minister in the 2006 and 2010 Maliki governments; Saad Qandil, former Iraqi ambassador to Tehran; and surgeon Alaa Amin Habbah, “who he decided to appoint as the director of his office” in case his government was approved.

The postmortem

According to Thaer al-Faili, a member of Allawi’s team present until the end and responsible for the indirect negotiations with Sadr that saw Allawi nominated, the cleric’s interview “was the straw that broke the camel’s back”.

However there were other issues too, the businessman, economist and former undersecretary said.

“Some political forces’ insistence on quotas reduced Allawi's chances of passing his government, especially after his great insistence on the independence of his government,” he told MEE.

According to Faili, no agreement with the Kurds was reached.

'Allawi is sincere, honest and brave, but unfortunately he lost the factors needed for success, intentionally or not'

- Thaer al-Faili, Allawi aide

“Allawi did not agree to give the Kurds what they wanted and I challenge anyone who says otherwise, and he also refused to give the Sunnis what they wanted,” he said.

Instead, Faili said, Allawi offered to grant the blocs permission for long-coveted projects, promising to front 80 percent of the bill through various means as long as the remaining 20 percent was provided by the parties themselves.

“Most of the Kurdish forces refused, as did the Halbousi alliance, while the Shia forces agreed,” Faili said.

Relying on Safwan al-Amin for negotiations and discarding friends with political influence and experience were also missteps by Allawi, he said.

“Also, his use of his sons was a mistake, although they are very smart, polite, well-educated and hard workers. But they do not know anything about Iraq and dealt with the situation with a British mentality,” Faili recalled.

“People understood this as laying the foundation for a family dictatorship, and this is not true. Allawi is sincere, honest and brave, but unfortunately he lost the factors needed for success, intentionally or not.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.