Palestinian village Farasin defiant despite threats of being wiped off the map

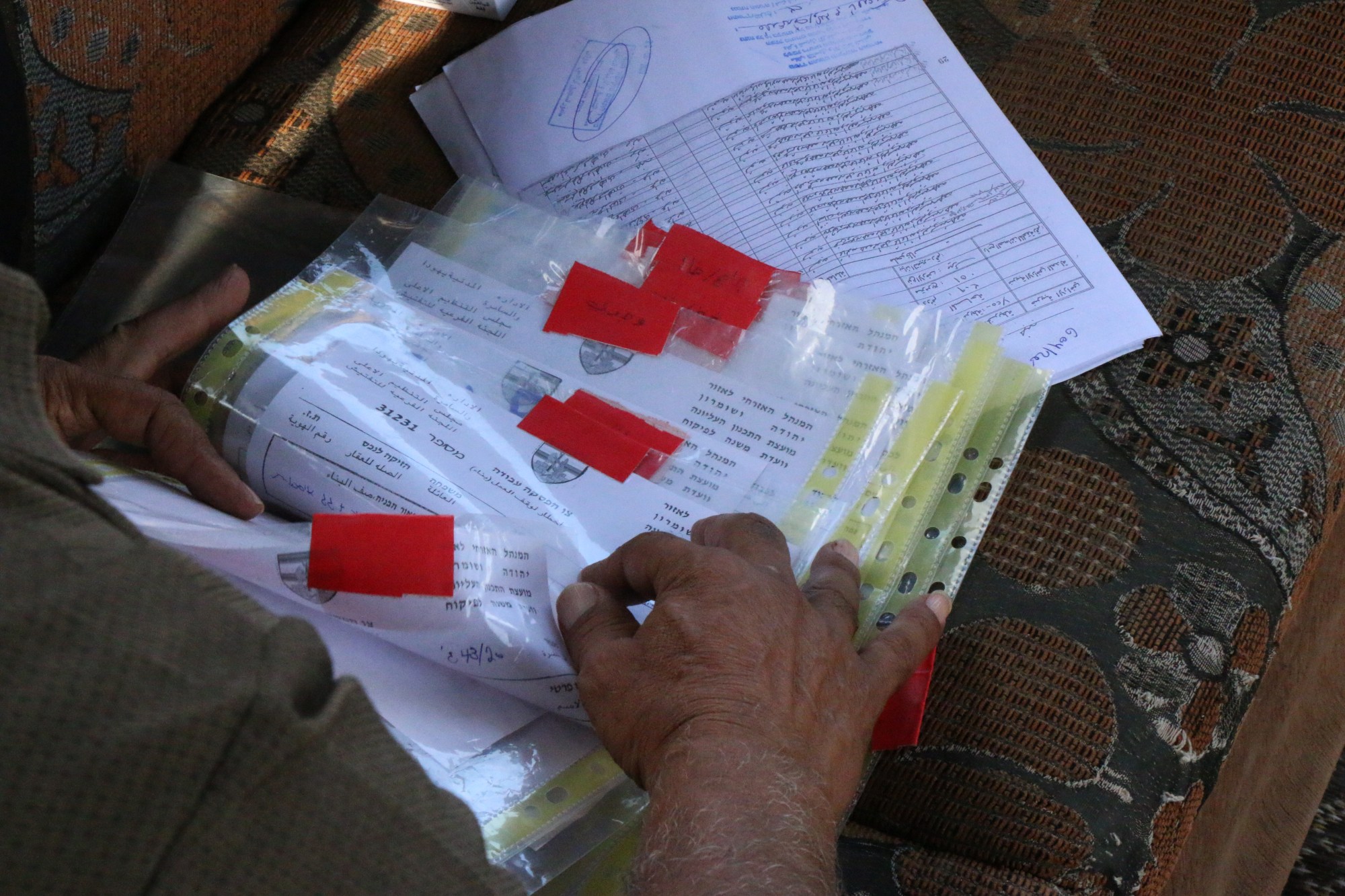

Sitting on the porch of his neighbour’s home, Mahmoud Amarneh, 56, shuffles through his briefcase, filled to the brim with papers and red-tabbed folders.

As the summer breeze passes through the tiny village of Farasin, the papers, printed in Hebrew and stamped with the insignia of the Israeli Civil Administration, go flying across the outdoor seating area.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Amarneh is the head of the village council in Farasin, a tiny hamlet in the northern occupied West Bank district of Jenin, just a few kilometres east of the Green Line.

Up until last week, Amarneh’s job was mostly symbolic, keeping the peace between the 200 residents of Farasin, who are mostly descendents of the same two families, settling any land disputes, and welcoming any visitors that may come to the village.

Now, he’s in charge of fighting what he says is a concentrated effort on the part of Israeli authorities to expel the people of Farasin from their land.

Over the past year and a half, Amarneh says Israeli authorities have ordered the demolition, evacuation, or construction freeze on every single of the 36 structures in Farasin.

“They have not left a single structure untouched,” he told Middle East Eye.

“Every home, every livestock pen, our local cistern, even these fences, they have some kind of order on them,” Amarneh said, pointing to a fence erected by locals to protect their livestock from wild boars in the area.

While the stop-work and demolition orders in Farasin have been distributed across the village for over a year, the vast majority of them were handed down to the villagers last week.

'It’s just one settler living there, but within months the Israeli government paved a road for him, hooked him up to the electricity network, and connected water lines to his outpost'

- Mahmoud Amarneh, council leader

“On 29 July, just before the Eid holiday, Israeli soldiers and Civil Administration authorities came into the village and delivered 18 orders at once,” Amarneh said. Just a few days before that, he said, four more stop-work and demolition orders had been given.

The 18 orders delivered on 29 July “finished off the village,” Amarneh said.

Of the 18 orders handed down last week, 15 were stop-work orders, while the remaining three gave 96 hours for residents to “remove” the structures in question, which included a well, a home, and an ancient cave still inhabited by residents of Farasin.

“We didn’t get to celebrate Eid this year,” Amarneh told MEE. “Usually, during Eid we exchange gifts, and give some money to the children. But this year, Israel’s Eid gift to us was 18 orders to ruin our village.”

First came settlers, then the demolitions

Like hundreds of other Palestinian towns and villages in the West Bank, all of Farasin’s land was designated as Area C under the Oslo Accords, putting it under the full Israeli military control.

The small hamlet consists mostly of tents and tiny homes made out of cement and tin sheets, scattered across a vast area of more than 6,800 dunams (1,690 acres) of land. It’s home to around 200 people, mostly shepherds and farmers, a quarter of whom are children under the age of 18.

Farasin was officially established in the 1920s, but Mahmoud Amarneh says Palestinians have inhabited the village’s natural caves for hundreds of years.

Over the years, as families grew, locals began to adapt their way of life, and started building permanent structures to live in.

Since Farasin is in Area C, any form of construction must be approved by the Israeli army’s Civil Administration - a nearly impossible task to achieve for Palestinians due to exorbitant fees and very low approval rates. But over the years, locals had faced little push back over the minor construction and home improvement projects that they undertook without permits.

All of that changed, however, when an Israeli settler moved onto Farasin’s land and established an illegal outpost there in 2019.

“You can see his caravans there, beyond those trees,” Mahmoud Amarneh said, pointing towards the 60-hectare forest on the edge of Farasin.

“It’s just one settler living there, but within months the Israeli government paved a road for him, hooked him up to the electricity network, and connected water lines to his outpost.”

Under international law, civilian settlements on occupied lands are illegal. While outposts are also technically illegal under Israeli law, in practice they are often dealt with leniently, if not outright supported by authorities.

Shortly after the settler moved in, Farasin’s problems began.

“At the same time that the Israeli government was setting up everything that the settler needed, they were coming and delivering demolition notices and stop work orders on our homes,” Mahmoud Amarneh said.

Any time residents would be working on construction of their homes or other structures, they would find surveillance drones, which they suspect were being controlled by the settler, flying above their homes.

“The settler will fly his drone overhead, and soon afterwards, the Civil Administration will come and conduct more surveillance in person,” he said, adding that when Israeli forces came to demolish two livestock pens in Farasin during Ramadan earlier this year, the bulldozers came from the direction of the settlement outpost.

Amarneh emphasised that while not all of the homes have explicit demolition orders against them, the villagers believe it is only a matter of time before the “stop-work” orders will turn into demolition notices.

If that happens, he warned, it will not only displace the 200 residents of the village, but completely erase Farasin from the map.

“It is ironic that this is our land, but we are being treated as if we are living here illegally,” Amarneh said. “Meanwhile, the settler who is actually here illegally is being treated like the owner of this land.”

“Our village has been here forever,” he continued. “And not just before the Oslo Accords were signed and this became Area C, but before the state of Israel was even created.”

Destruction in the name of preservation

On the highest point of Farasin, crumbling stone structures reportedly dating back 500 years overlook the village and the surrounding area.

Local merchants erected the buildings in the 1800s, using them as a resting and trading point for travellers and merchants coming from countries like Lebanon and Syria, through what is now Farasin, and into Palestine.

Now, the buildings are home to 42-year-old Yusuf Amarneh, his wife, and five children. Over the past few years, after living in tents and makeshift houses, Yusuf has dedicated his time to restoring the ancient buildings, whose ownership was passed down in his family for generations.

“Over time, the structures have started to crumble, but I’ve managed to restore much of the main house, using mostly the original stones,” Yusuf says proudly, emphasising the fact that while making a home for his family, he’s prioritised preserving the integrity of the original structure.

'These are ancient caves that people have lived in for hundreds of years - how do they intend on ‘removing’ these caves? They are part of the land'

- Mahmoud Armaneh, , Farasin village council head

So when Israeli authorities arrived at his doorstep last week and ordered him to stop work under the pretext that he was “destroying a cultural artifact”, Yusuf was shocked.

“They told me that if I did not stop working on the house, that they would fine me and destroy it,” he said. “How does that make sense? They say that I am destroying cultural artifacts by rehabilitating this structure, but at the same time they want to demolish it?”

In addition to the order on his home, Yusuf Amarneh was also ordered to remove the water tanks he had set up on his property to make life easier for himself and his family.

According to Mahmoud Amarneh, similar stop-work and “removal” orders were given to families living in ancient caves in the village, also under the pretext of “destroying cultural artifacts”.

“These are ancient caves that people have lived in for hundreds of years,” he said, asking, “how do they intend on ‘removing’ these caves? They are part of the land.”

“This is our way of life, so how can the Israeli occupation say that we are destroying culture, when this is our culture and our land to begin with?”

Dreams shattered

Yusuf Amarneh’s story is one shared by all the residents of Farasin. Every single family, including that of village council leader Mahmoud, is under threat.

‘How can the Israeli occupation say that we are destroying culture, when this is our culture and our land to begin with?’

- Mahmoud Amarneh, Farasin village council head

Wajdi Amarneh, 37, is a husband and father of four young children. Like most other residents of the village, he is a subsistence farmer, and spends his time growing and harvesting crops and raising livestock to feed his family.

“We have a simple life here,” he told MEE. “We live off the land, and farm mostly for sustenance, rather than as a business.”

For years, Wajdi and his family had been living in a tent. But as his family grew, he wanted to provide his children with more safety and security, so he decided to build a tiny one-room home on his land.

Wajdi began selling whatever crops or livestock not used by his family, and over the years saved up enough money to build his home, which he finished last year. With the help of the village council, he applied to have his house registered and permitted by the Israeli Civil Administration.

“I was shocked when they came last week and told me I had 96 hours to demolish my home,” Wajdi said. “I have an open file with the Civil Administration, so it shouldn’t be allowed to demolish my home while the case is still open.

“How is my little home affecting Israel in any way? I am on my land, just trying to live in peace with my wife and children. This shouldn’t be illegal,” he said.

The 96-hour deadline to demolish his own home passed on Monday, and Wajdi says that while the stress is definitely affecting his family, they aren’t going anywhere.

“Now, any time my kids see any Israeli army or Civil Administration vehicles passing by, they start crying and screaming, saying ‘they are coming to destroy our house’,” Wajdi said. “It’s a terrible feeling.

“Even if they do come, and God forbid, destroy my house, I will not leave. Maybe I will have to live in a tent again, but I would rather live in a tent or even on a mattress on the ground before I leave this place.”

Annexation

As the sun set on Farasin, cloaking the village in pink and orange hues, the residents and their families gathered outside Wajdi’s home for an evening cup of tea.

'I would rather live in a tent or even on a mattress on the ground before I leave this place'

- Wajdi Amarneh, Farasin resident

In the distance, skyscrapers and buildings from the city of Caesarea in Israel peaked through the haze - a reminder that just a few kilometres away, Israelis were living a completely different reality to the one of Farasin’s residents.

While the residents of Farasin attribute much of their problems to the arrival of an Israeli settler last year, there’s no denying that regional politics are playing a role in their struggle.

“Israelis are trying to create facts on the ground,” Mahmoud Amarneh said. “So that way, when annexation comes around, or the Trump plan is put into action, they can say that this land belongs to them, and it should be a part of Israel.”

The council leader was referring both to open plans by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to annex large swathes of the West Bank, and US President Donald Trump’s much contested plan for Israel and Palestine.

What’s happening in Farasin, Mahmoud pointed out, is happening across the West Bank.

“This is a small example of Israel’s settler colonialism,” he said. “They want the land, but not the people that are living on it.

“Even if they come tomorrow and destroy our entire village,” he said, “we will not leave. This is our land, and we are here to stay.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.