Forbidden: The West Bank land Israel locks away from Palestinians

At 7am on 2 November, dozens of cars carrying some 35 Palestinian families lined up one after the other at the entrance to the village of Janiya, northwest of Ramallah city, awaiting permission from the Israeli army to access their farming lands.

The families were kept waiting for more than three hours; the children got fussy and the adults were starting to lose their patience, as soldiers slowly took up positions in the area.

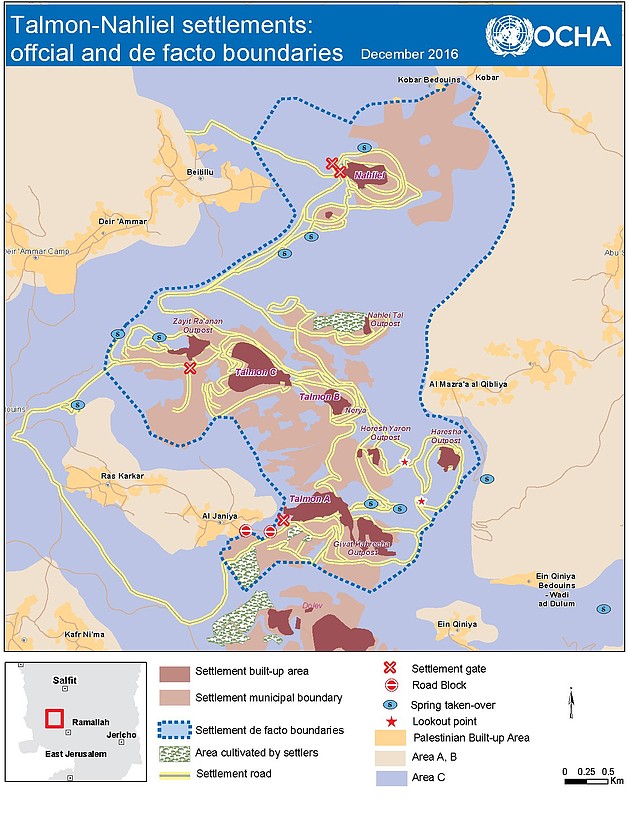

Just after 10am, the soldiers collected everyone’s ID and gave the signal allowing the entrance of the Palestinian convoy, flanked by the army. The cars would have to pass through the settlement of "Talmon A," and would be forced to exit the same way in a few hours.

Janiya village is almost completely encircled by Jewish settlements.

Since the early 1990s, when settlers took over the surrounding areas, the army allows Palestinians access to their farms only twice a year, for a day each time. But in the last two years they were prevented from visiting their land by the army for the sole reason that the harvest season coincided with Jewish holidays.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Being able to visit is a special occasion for the Palestinian families, despite living only a 10-minute drive away in the village.

Nabiha is mother to 10 children, and grandmother to about 80. The 85-year-old came here in a wheelchair with about 30 of her family members, wearing a traditional embroidered Palestinian thobe which she carefully picked out the night before.

With a few words, Nabiha described her memories on the farm: “We used to spend all of the summer season here and stay until the olive harvest season in October. We grew all types of summer vegetables: I remember the tomato plant once produced 16 tomatoes! We would sell our produce in nearby villages, and once winter came, we would return to our homes in Janiya.”

When the family arrived at their plot of land of about 20 dunum (2 hectares), Nabiha sat in front of the water spring near what was once their house. Today, the building was empty, its doors and windows had been broken off, and there was garbage on the floor left by others who came before them.

For a while, Nabiha stared into the field, recited a sad song for her late husband, and refused to talk to anyone. She used this time to relive her precious memories in this place.

It was no longer how she remembered it. Settlers had installed swings and wooden seats in every corner and planted new trees. They had gathered here all-year round near the Umm Siraj water spring that poured into the pool in front of Nabiha’s home.

She refused to describe her land as confiscated, as long as she was able to return to it, even if it’s only once during an entire year.

“This land was a piece of heaven – we used to cultivate it three times a year. The sand was red and had no stones in it. The pool was always clean; we would drink from it and water the plants with it,” Nabiha told Middle East Eye, surrounded by her grandchildren who were engrossed in their grandmother’s stories about this place.

Each time the family returned, they saw fewer and fewer olive trees after the settlers cut them down. This time, they were shocked to find the largest and the oldest tree split in half.

Sadness reigned over the family as though they had lost one of their relatives. “We would spend three days picking olives from this tree,” said Mayza, one of Nabiha’s daughters. “There is no pain equivalent to that of losing this tree. I’ve lost the will for everything.”

Mayza spent the rest of the day in silence.

Race against the clock

The family worked as fast as they could in a race against the clock. At 3pm, the soldiers would arrive and tell them to leave the land, even if they hadn’t finished their work. Nabiha’s daughter, Fatima, and her 19-year-old daughter Mariam, picked the olives like machines, without stopping, in anticipation of the army’s arrival.

Fatima, 50, awoke early and prepared pastries to bring with her for breakfast. She said she couldn’t sleep the night before, brimming with excitement.

Her eyes lit up as she looked around the farm. “My mother would bring us here when we were children, we would spend eight months of the year here. It is basically where we grew up – it’s not just our memories, our souls are here as well,” Fatima told MEE.

“My siblings and I learned how to swim in this pool,” she continued, pointing at the now-empty pond.

She noted that in the springtime, the land would flourish with flowers, which she and her siblings had memorised the names of as children. “I recall that there was a beehive on one of the olive trees. We were too afraid to go near it.”

Israeli restrictions on the Palestinian families’ visits intensify with each passing year, aiming to discourage them from returning. As a result, the land has suffered, as well as its caretakers.

“The land and the trees here are in need of care, they have been neglected. Some of the olive trees have stopped producing, so a number of the families no longer come here,” said Fatima.

“When my father saw what had happened to our land the first time we were allowed back, he had a heart attack. From then on, his health deteriorated, until he died in 2009,” she continued.

Mariam, Fatima’s daughter, cried as she listened to her mother speak. “Picking olives was one of our favourite family activities, even though it is tiring. The experiences of our parents and families here meant that we grew up inheriting attachment and love for this land,” she said.

Three Israeli soldiers stood guard as the family worked on the land.

“The settlers behave as though this land is theirs, and we are the guests coming to visit it. This angers us, and means that we’ll continue confronting this challenge by coming here when we can and not giving it up,” Mariam said.

The family decided to harvest their crops early, fearing that Israeli authorities wouldn’t allow them back in during harvest season next year. “We live in a constant state of fear and anxiety over losing this land to the settlers… it is surrounded and dominated by settlements,” said Fatima.

Tayseer Abu Fkhaida, head of the local village council, described the Umm Siraj water spring area as one of the most fertile in the region, dotted with ancient Roman olive trees and producing high quality olive oil.

Thousands of dunums had already been confiscated from Janiya village lands, he told MEE.

“Some 65 percent of the land was already taken. Today, the village retains only 3,000 dunums out of the original 8,000.”

“We fear that the area will be confiscated. The settlers and the army try to impose a fait accompli situation. We expect that at any moment we’ll be forbidden from accessing our lands completely,” Abu Fkhaida said.

At about 3.30pm, the army decided that time was up and began moving the families out of the area, even though they had not yet finished work.

When it was time to leave, the army held them up for about two hours claiming to check IDs, stretching out the tiresome journey that was once a short walking distance from their homes in the village.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.