Even in death, Algerian war veteran and Hirak activist defies authorities

Condolences have been pouring in for a prominent Algerian war veteran after news of his death broke on Wednesday evening.

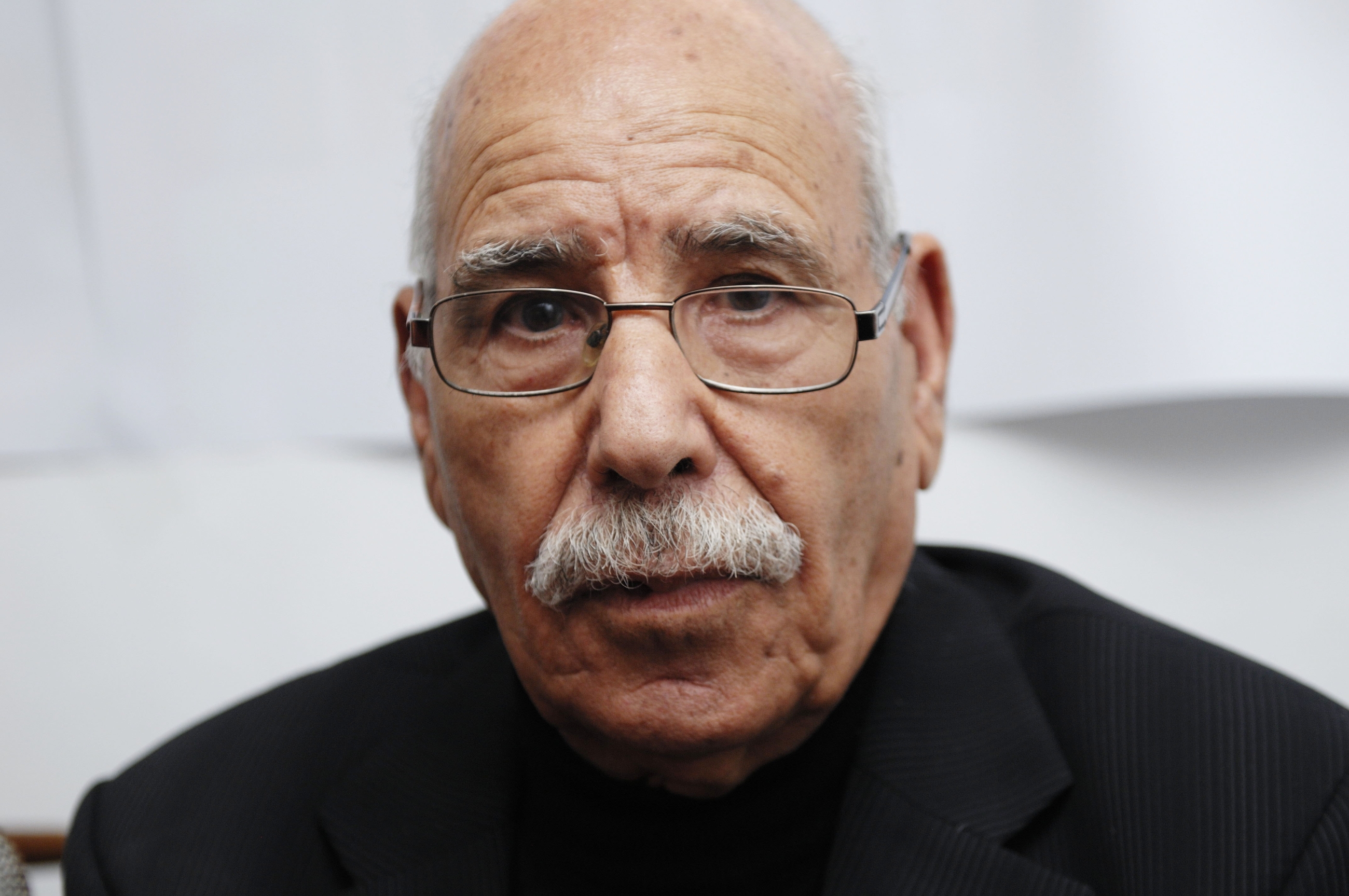

Lakhdar Bouregaa, a revered veteran of the war of independence against France and a figure in Algeria's popular Hirak, died at the age of 87 after he was hospitalised in Algiers on 21 October after testing positive for Covid-19.

Earlier media reports stated that he would be buried in the El Alia cemetery in the capital, where prominent figures of the war of liberation and former heads of state are interred. However, Bouregaa’s son, Hani, refuted the claims on his Facebook page, confirming that his father will be buried at the Sidi Yahia cemetery in Hydra, honouring his dying wish.

Bouregaa’s decision mirrors that of another revolutionary national figure, Hocine Ait Ahmed, who also refused to be buried in the cemetery.

A 'tireless activist'

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Born on 15 March 1933, Bouregaa was a senior military official in the National Liberation Army (NLA) from 1956, and assumed control of Wilaya IV, covering the north of Algeria, during the nearly eight-year-long bloody conflict to gain independence from France.

Following independence, Bouregaa went on to become a founding member of the Socialist Forces Front (FFS) in 1963, Algeria's oldest opposition party, and as a result he became a political prisoner from 1967 to 1975, under the presidency of Houari Boumediene, after he was charged with conspiracy to murder Boumediene and plan a coup.

"Algeria is losing a man of great stature,” the FFS said in a statement. “Millions of Algerians will retain the image of him as a tireless activist who, despite his old age and illness, chose to continue his struggle for a democratic state."

Mohcine Belabbas, president of the Rally for Culture and Democracy, described Bouregaa as "a landmark for the youth", and a man who "remained faithful to his oath after independence".

"He is one of the symbols of struggle against colonialism... and because of his struggle, he suffered a great injustice," prominent lawyer Mustapha Bouchachi said on Thursday.

Translation: "A great man has just left us. Dedicating his life to Algeria. He never stopped fighting, but he left us to join eternity. Si Lakhdar Bouregaa is no more. History will not forget you. God have mercy on you."

Smear campaign

At 86, Bouregaa, who was a member of the National Organisation of Mujahideen, was imprisoned from 30 June 2019 to 2 January for his role in the Hirak, the movement which began in February 2019 in protest at Abdelaziz Bouteflika seeking a fifth term in office.

Bouregaa was charged with "insulting a state body" and "participating in a company demoralising the army with the aim of harming national defence".

His arrest and subsequent detention sparked outrage in Algeria and provoked a defamation campaign in local media, which questioned his role in the independence war and accused him of being an agent of the French army between 1954 and 1956, in order to legitimise his detention.

Bouregaa, who threatened to go on hunger strike in protest at his detention, rejected the possibility of an earlier release due to the incarceration of dozens of young protesters – he demanded their release as a condition for his own.

During his trial, he refused to answer the judge's questions, stating that he did not recognise “the judge of an illegitimate system”. In November 2019 he underwent surgery for a hernia and was released on 2 January, and was subsequently fined $750 during a trial held on 12 March.

The National Committee for the Liberation of Detainees has called on Algerians to take part in a balcony protest, banging a traditional pot called the mahraz in remembrance of Bouregaa and more than 70 detainees currently imprisoned as part of the government’s crackdown on dissent.

Banging the mahraz from windows and balconies was a tactic used by Algerian families during the colonial period to warn the neighbourhood of the arrival of French soldiers in pursuit of independence fighters. It has been used a number of times since the pandemic halted street mobilisations.

In a memoir, Bouregaa wrote, “for me, as for many generations, the war of liberation was not only the beginning of a new life, of a new era, but a birth certificate, a founding act of who we are, of what we should have been, what we should never have ceased to be: free men. Algerians living freely in a free country.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.