'Propaganda? So what?': Armenian genocide dispute goes to Hollywood

ISTANBUL, Turkey – They are tales told by A-list stars, of all-American heroes and heroines caught in love triangles and conflict against a backdrop of awe-inspiring, exotic Turkish scenery.

The Ottoman Lieutenant and The Promise, two films set in the First World War, are Hollywood to their cores: romantic dramas with western protagonists very much front and centre.

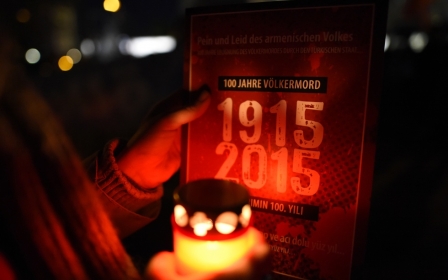

But behind the romance and glamour lies another story: Turkey versus Armenia, and their conflicting views on the horrific events of 1915 in Anatolia that left up to 1.5 million Armenians dead.

Both countries are now backing a rival Hollywood blockbuster to promote their version of the tragedy: Armenians have The Promise, while Turkey has part-funded The Ottoman Lieutenant.

At the centre of both is the dispute over what happened in 1915, on which both countries continue to expend almost inexaustible energy to make the world and its governments accept their version of events.

Armenians say the result of the Ottoman Empire’s rounding up and expelling of Armenian nationals was genocide. Turkey rejects the term, calling it a tragic result of confusion and paranoia in the dying days of an empire at war.

And it is now that this 100-year international row has made it to the silver screen: The Promise, starring Christian Bale, Charlotte Le Bon, Oscar Isaac and Jean Reno, puts the "genocide" firmly in focus. The Ottoman Lieutenant, starring Ben Kingsley, Hera Hilmar, Josh Hartnet and Michiel Huisman, is set a short time before and makes only passing mention of the tragedy.

Both communities have accused each other of producing "propaganda," with claims and counter claims that poor reviews are the result of manipulation and internet campaigns to torpedo each other's film.

The Ottoman Lieutenant, supported as part of the Turkish government’s cultural incentives, is a melodramatic love story that plays out in eastern Anatolia and involves a love triangle between an American nurse, a Turkish lieutenant in the Ottoman army and a devoted young American doctor in the area.

The movie hints at the wariness with which leaders in the then imperial capital Istanbul view the loyalties of their Armenian subjects in the east - but that is as far as it goes.

The Promise is also pure melodrama, focusing on a love triangle between an Armenian medical student, an American journalist, and the Armenian woman who steals their hearts. All three find themselves grappling with the Ottoman decision to begin rounding up and persecuting Armenians.

The Promise was produced by Survival Pictures, established by legendary diaspora Armenian Kirk Kirkorian before his death in 2015. Kirkorian also owned major Hollywood studios MGM and United Artists at various times in his life.

Plenty of eyebrows have been raised over making such a large-scale tragedy the background in films about love affairs, spectacular imagery and American heroes in an era and region where their involvement was minimal.

Yet both the Armenian and Turkish communities appear resigned to the fact that it is the only way to capture the attention of and tell their stories to American audiences.

Ali Murat Guven, a respected film critic from Turkey’s Islamist conservative circle, told Middle East Eye that dropping American heroes into events they had no part of is often the only way to get one’s message across.

"To portray such a tragic event in such a light is not ideal, but Americans are massive egoists and they won’t bother to watch anything that doesn’t portray them as the main heroes," said Guven.

"Plus it is preferable to trying to create a grim picture which is equally untrue - like the Armenians did in the past."

The movie from the past that Guven refers to is Atom Egoyan’s Ararat.

Love stories show the better side of mankind and provides a sharp contrast to how people behaved in 1915

- Garbis Sarafian, Armenian diaspora

In Guven’s opinion, the film’s inclusion of blatantly untrue and gruesome scenes - such as the rape of an Armenian corpse by a Turkish officer - was why the movie was slammed by both Turks and Armenians.

Garbis Sarafian, an Armenian from Turkey who has lived in Los Angeles for the last 35 years, prefers that such a tragic incident remain in the backdrop of films.

"Personally I find it better when love stories and other positive human relations take precedence in such films," he said.

"It shows the better side of mankind and provides a sharp contrast to how people behaved in 1915."

Other attempts to depict what happened, like in Atom Egoyan’s film, just results in bans and blockages," said Sarafian, who also works with the LA-based Armenian NGO the Organisation of Istanbul Armenians.

"In any case our community has given strong backing to The Promise. It is a truth that needs telling."

The Ottoman Lieutenant, with an estimated production budget of $40m, did poorly at the US box office following its release in March, generating just $240,978 in revenue amid mixed reviews.

According to Guven, there are two reasons for this: poor marketing and the Armenian diaspora.

"The film only managed to get shown on 216 screens, which is minor in the US where major films open on more than 3,000," he said.

"But mostly it is the work of diaspora Armenians. They cannot stand anything Turkish. They started attacking the film even before they had seen it just because it is a joint Turkish production."

Guven also attributed some of the reviews which call the film propagandist to the Armenian diaspora.

As Dennis Harvey wrote in Variety: "Hot on the heels of George Mendeluk’s Bitter Harvest, Joseph Ruben’s The Ottoman Lieutenant offers another theoretically noble if B-grade and somewhat propagandistic attempt to shed light on a murky historical chapter - while falling into a similar puddle of romance-novel cliches from which it can't get up."

Guven said it was "hawkish Armenians" in the diaspora who had rejected Turkish gestures made in the past 15 years to re-establish the bonds of friendship.

"Turkey has evolved. Unlike the Turkey of 40-50 years ago when any mention of 1915 was taboo, we debate it freely now.

"Turkey will never accept the term genocide, but even the president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, in 2014 when he was still prime minister expressed his condolences for the events of 1915, the first Turkish leader to do so.

"But none of Turkey’s gestures have been reciprocated. If the Armenian hawks expect some sort of Nuremberg trial where Turkey will fall to its knees and say it committed genocide, they are dreaming."

Sarafian, by no means one of the diaspora "hawks,"said the way to reconciliation lay in acceptance of reality and facts.

"We have to be able to accept reality. For me the reality that cannot be denied is that my uncle was only one of four people from his village to survive.

"What did all those women and children do? Were they crooks? Did they take part in an insurrection? No.

"Once we can accept what happened and then approach each other without prejudice but with complete knowledge, then the path to reconciliation begins."

The Promise, with its estimated $100m production costs, has also fallen flat with reviewers, and, just like the Turks, the Armenian community as well sees "hidden hands" behinds its 5.4 rating on the Internet Movie Database (IMDB).

So what if it is propaganda? At least it is trying to say we can live alongside each other

- Ali Murat Guven, film critic

The Promise took $4.1m over the weekend after launching on 2,251 screens across the US. The intake was lower than producers' expectations.

"Some people are just going on IMDB and giving the film zero points to lower its ratings without even seeing it," said Sarafian. "This has created unhappiness in our community and increased support for the film. We are now actively promoting it."

Both films were scheduled originally to hit screens in 2015, the centennial of the 1915 events, but various snags resulted in a two-year delay for both movies.

Guven said the Turkish-backed film was outright dismissed by the diaspora Armenians as "cheap Turkish propaganda".

"So what if it is propaganda? At least it is trying to say that despite everything we can still live alongside each other and doesn’t depict any side as evil.

"But to reconcile, Turkish gestures of friendship need to be reciprocated."

One thing both Guven and Sarafian are agreed upon is the need to communicate without prejudice.

"Listen, forget if it was 800,000 or 1.5 million people who lost their lives," said Guven. "I would have deep remorse if even just eight innocents lost their lives.

"I feel deep remorse. But we need to look to the future. Time has moved on and it is not right to push away our extended hand of friendship.

"We lived alongside each other peacefully and in friendship for a thousand years and we should again."

Sarafian adds: "I might have lived in Los Angeles for the last 35 years, but I still have my Turkish traditions.

"That is my culture and how I grew up. We just need to talk to each other without prejudice."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.