'Radical Love Book' hailed as key to Turkish opposition election success

Turkey's beleaguered opposition won a rare victory in last week's local elections, taking many of the country’s largest cities, which represent a big chunk of the country's GDP and hold huge symbolic value.

The secularist Republican People's Party (CHP), Turkey's oldest party and the largest opposition party, ended a quarter-century of religious conservative rule in the capital Ankara and megalopolis Istanbul, the latter of which is still being contested by the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP).

Faced with President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's polarising invectives labelling them as terrorists, the CHP tried a new strategy: being nice.

"Whatever wounds were opened before, in order to heal them, we will meet individually with every segment of society, every ethnic identity, every religious group," said the CHP candidate for Istanbul, Ekrem Imamoglu, shortly after the elections.

When did the world become this loveless?

- Radical Love Book

Imamoglu said he would be "a mayor of all citizens regardless of background, ethnicity or religion," encouraging his supporters to do the same and pledging to provide his

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The basis for the new strategy is a publication produced by Ates Ilyas Bassoy, the head of campaigning for the CHP, called the Radical Love Book.

"[Imamoglu] always speaks politely and courteously. When he talks like that, the [AKP] doesn't know what to do," said Bassoy, speaking to Middle East Eye.

Bassoy's communications strategy is to avoid being reactionary and rising to the AKP's bait.

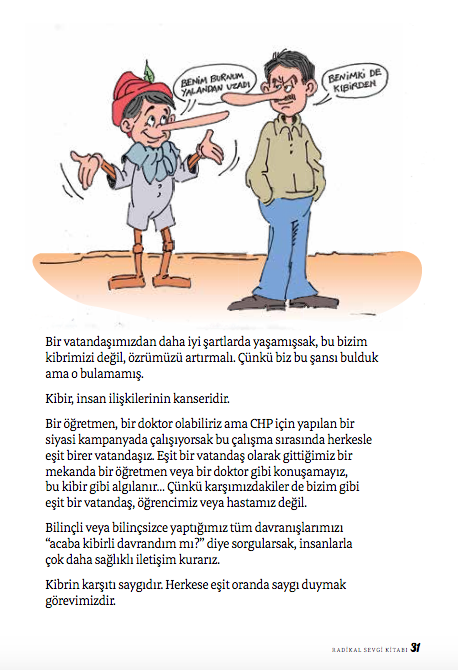

Instead of attacking their opponents, he instructed CHP's politicians to let go of "the language of rage," eschew cynicism and vanity, and speak the "language of love".

"I worked with all the mayors who were elected. I told them they need to update their language," he said.

He wrote the Radical Love Book after a four-month tour of Turkey and distributed it within the party shortly before the elections.

The book, illustrated with colourful flowers and funny cartoons, is written in an almost hippy tone, insisting that it’s not a campaign strategy but a philosophy.

It opens: "In the endless emptiness of space, there's life on a tiny little planet. But there's always fighting on this planet.

"When did the world become this loveless?”

It goes on to urge canvassing politicians to spend more time listening than speaking.

When they do speak, they should use language that's concrete, inclusionary, down-to-earth and calm, and should often employ humour.

"I think the CHP has been doing politics wrong for ages, and that always worked in the AKP's favour," Bassoy said.

"Turkey has been making the same mistake for years, belittling and swearing at Erdogan, telling him how ignorant he is, but this only bolsters his support, much like Donald Trump in the United States."

Putting the strategy into practice, the CHP's winner in Izmir, Tunc Soyer, paid his first visit to the district where the fewest people voted for him.

After the CHP's candidate Mansur Yavas won in Ankara, he said: "We don't have any grudges or discrimination against those who didn't vote for us."

Angry rhetoric

These words may sound saccharine, but in today's Turkey, riven by culture wars and Game of Thrones-style political discourse, they are practically revolutionary.

President Erdogan and his allies have long made it their strategy to stir up tensions between groups in Turkey’s highly polarised society and regularly refer to their political opponents as terrorists, criminals, atheists and traitors.

The run-up to this election was no different, as Erdogan associated several CHP politicians with terrorism and crime, and called the election "a matter of survival against those who want to divide this country and tear it to pieces".

After the opposition's victories, Erdogan referred to the election as an "organised crime" and called for the results in Istanbul to be annulled. Meanwhile, an AKP winner in Samsun promised to prioritise the neighbourhoods that voted for him the most.

Mainstream media, almost entirely government-controlled, went even further. A presenter on Akit TV called for the hanging of CHP head Kemal Kilicdaroglu (the channel later apologised) and at least two papers referred to the opposition's electoral win as a "coup".

Aykan Erdemir, a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defence of Democracies and former CHP parliamentarian, said the Radical Love Book was the fruition of the changes that started when Kilicdaroglu became head of the CHP in 2010.

"This booklet is almost like a manifesto of what the CHP has been trying to do over the last nine years," he explained.

Erdemir says the philosophy of "radical love" is aimed to counter kibir – a Turkish word conveying elements of arrogance, vanity and hubris.

"I would argue that this is a perfect antidote to a regime that is built on hate and scapegoating."

Changing strategy

The CHP has long been dismissed as elitist, effete and stodgy, not to mention hostile to observant Muslims and ethnic minorities. In the 1990s and early 2000s, the party was ruled with an iron fist by Deniz Baykal.

Its members often used polarising rhetoric that fed into cultural animosities between secular nationalists, religious conservatives and Kurds.

"The CHP's main obstacle to winning elections in Turkey had to do with the manner in which opposition politicians interacted with the electorate," said Erdemir.

The party still inspires images, whether historically accurate or not, of gendarmerie soldiers preventing students from studying the Quran, mosques being turned into warehouses and people being hanged for not wearing western-style hats, according to Halil Yenigun, a Turkish scholar at Stanford University who comes from a religious conservative background.

The AKP now resembles the CHP of the olden days

- Halil Yenigun, academic

"In the past, the CHP used a very anti-people language [and] despised the [masses] and their lifestyles," Yenigun argued.

After Deniz Baykal resigned as head of the CHP following a sex-tape scandal in 2010, current leader Kemal Kılıcdaroglu became the new head of the party. A slow revolution took place as Kilicdaroglu democratised the party internally and brought in many young social democrats.

The party now seems to have given up its "civilising approach towards the masses in Anatolia," Yenigun said.

"They've come to terms with what Turkey is and how Turkish people are."

As a result, many religious conservatives no longer view the CHP as unfavourably as in the past.

CHP's Istanbul election winner Imamoglu is himself openly religious, and a viral video shows him reciting a verse from the Quran at a mosque after the recent terror attack in Christchurch, New Zealand.

He has made many public appearances with his headscarf-wearing mother and often engages playfully with AKP supporters while on the campaign trail.

"The CHP has been seen by the general public as a party which has little or zero sympathy for people with strong religious beliefs, and Imamoglu is the exact opposite of this understanding," said Fehmi Koru, a prominent conservative columnist.

Imamoglu's wife Dilek also received praise for denouncing social media posts mocking AKP Istanbul candidate Binali Yildirim's headscarf-wearing wife Semiha for appearing less modern than Dilek, who doesn't wear a headscarf.

Dilek told the daily Cumhuriyet: "If they think they're insulting or praising someone, they should know that they're also insulting me. Because when I look at Semiha Yildirim's photo, I see my own mother, I see my big sister."

Yenigun stressed that the CHP still could not be considered genuinely liberal by international standards, and its approach to the country's sizeable Kurdish minority will be the real litmus test.

Berk Esen, a professor at Ankara's Bilkent University, also said it was hard to say how much of a role the CHP's more inclusive political style had in its election victories, and it shouldn't be overstated.

He says the main reason for the opposition's electoral success was the AKP's disastrous mismanagement of Turkey's economy.

Esen said the opposition's victories, buttressed by a smart selection of competent, catch-all candidates from the centre-right and left, are nonetheless impressive, considering the context.

He also argued that Turkey wasn't a true democracy, but a competitive authoritarian regime, where one party controls state institutions and the media, and highly unfair elections still occur.

"By having a very civil discourse, by keeping their calm, by coming up with a moderate agenda, by appealing to religious voters … the CHP candidates managed to overcome these structural disadvantages," he said.

Yenigun says it's now the AKP that appears calcified, ideological and out of touch. The party has created its own elite, similar to the secular elite of the past, which has generated great resentment.

"The AKP now resembles the CHP of the olden days," he said.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.