Red Sea cables: How UK and US spy agencies listen to the Middle East

The growth of Middle Eastern fibre optic cable networks has given Western signals intelligence agencies unprecedented access to the region’s data and communications traffic.

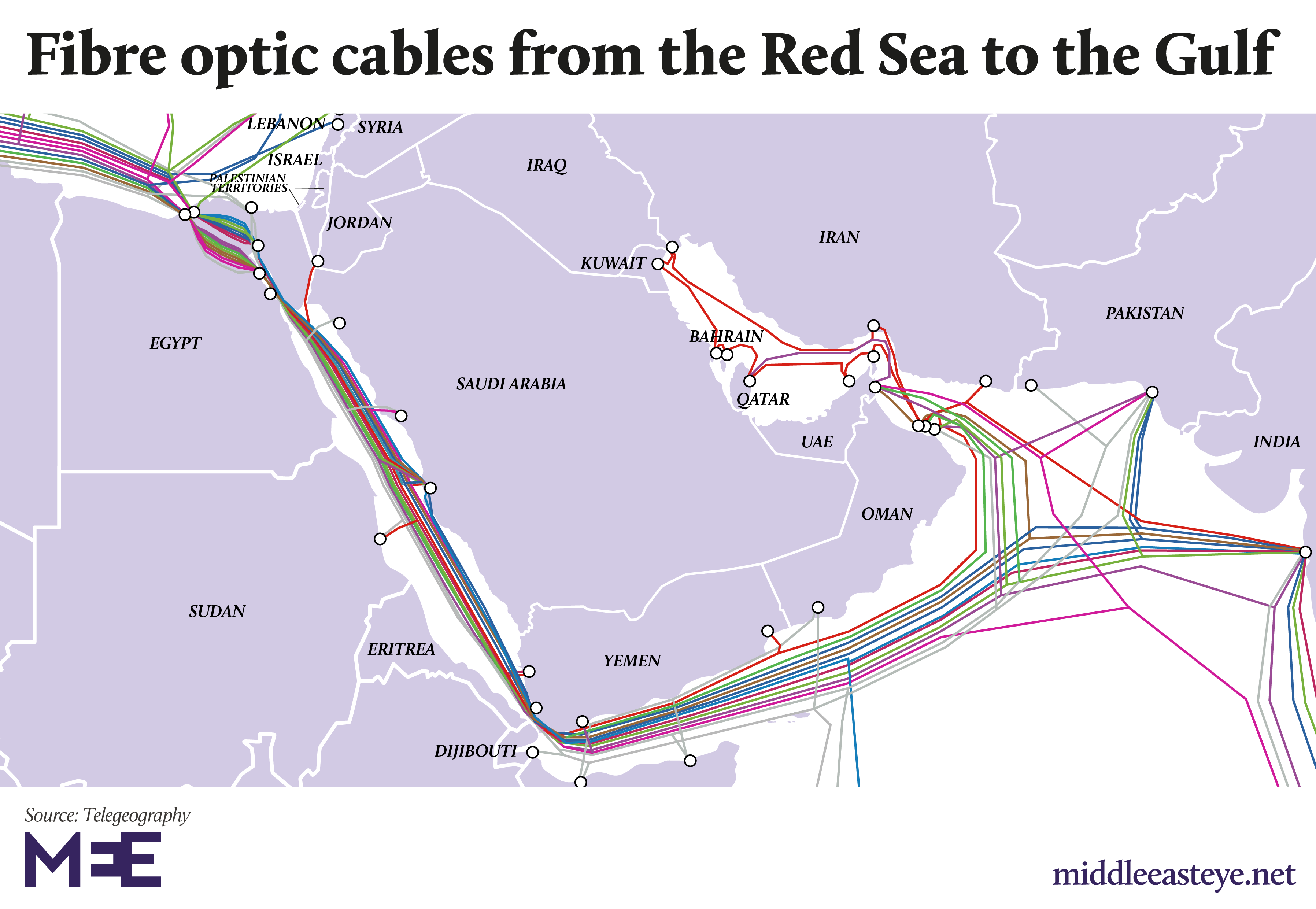

“There is no question that, in the broadest sense, from Port Said [in Egypt] to Oman is one of the greatest areas for telecommunications traffic and therefore surveillance. Everything about the Middle East goes through that region except for the odd link through Turkey,” said Duncan Campbell, an investigative journalist specialising in surveillance since 1975.

The Five Eyes, a signals intelligence (SIGINT) alliance of the US, the UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, has been snooping on the Middle East since the network was formed during the Second World War.

The key players are the US’s National Security Agency (NSA), and the UK’s Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), utilising both known and secret facilities in the region to collect data.

The Middle East is a hotbed of surveillance for obvious reasons: its strategic political-economic importance, the Arab-Israeli conflict, and political divisions between the allies of the Five Eyes and their adversaries, from militant groups to countries such as Iran and Syria.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

While all conventional forms of surveillance are carried out, from airspace surveillance to tapping phone lines, the region is a strategic asset for mass surveillance due to the current routes of fibre optic cables.

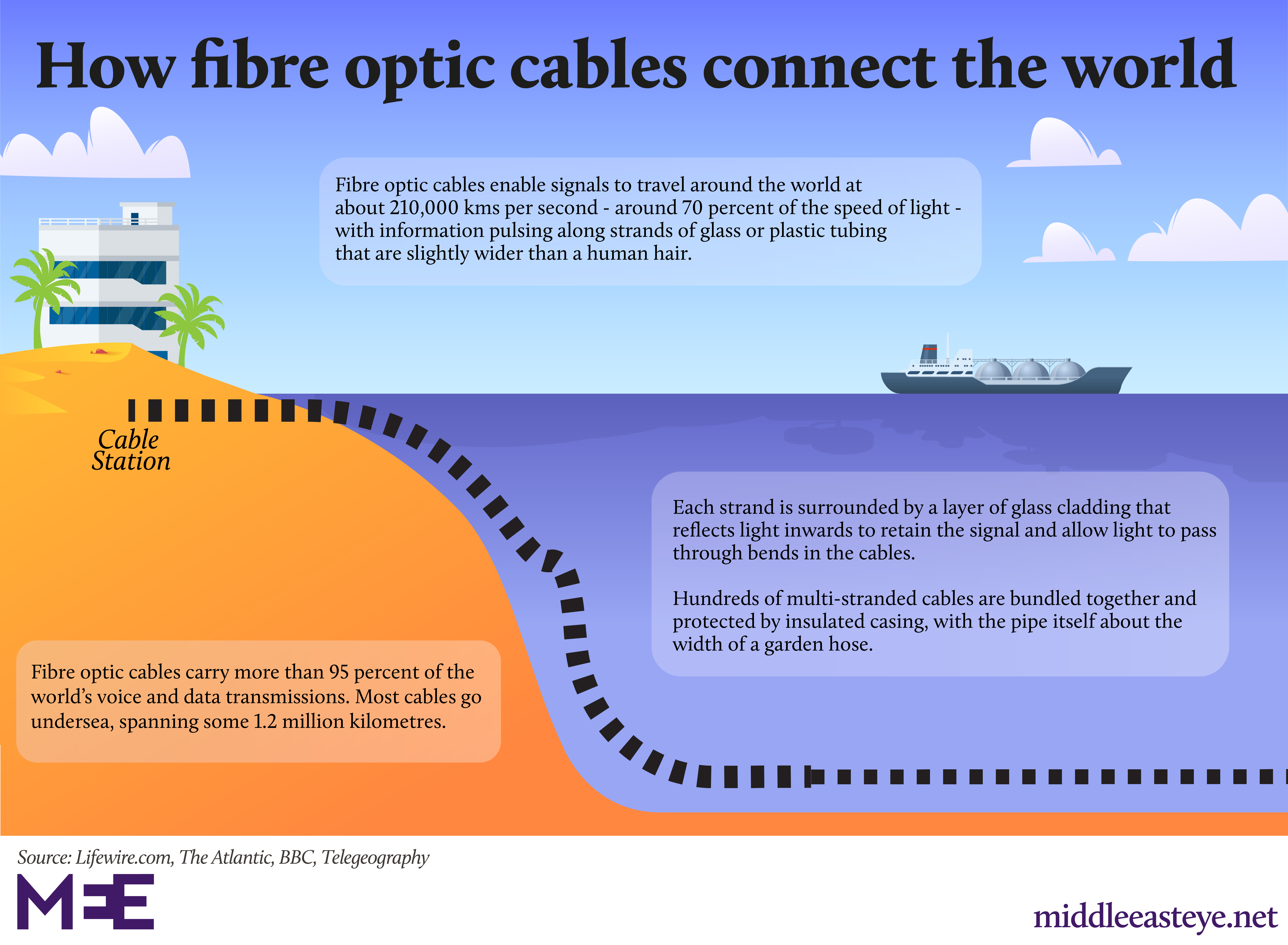

“The importance of cables is still largely unknown by the average person. They think smartphones are wireless and it goes through the air but they don’t realise it is through cables,” said Alan Mauldin, research director at telecommunications research firm TeleGeography in Washington.

Spy agencies have tapped into fibre optic cables to intercept vast volumes of data, from phone calls to the content of emails, to web browsing history and metadata. Financial, military and government data also passes through cables.

Such intercepted data is sifted by analysts, while filters extract material based on the NSA and GCHQ’s 40,000 search terms – subjects, phone numbers and email addresses - for closer inspection.

“This physical system of fibre optic cables joins the major countries of the world and carries over 95 percent of international voice and data traffic. Given the importance of undersea cables, they are poorly protected by international law," said Athina Karatzogianni, an academic researching the importance and regulation of undersea cables.

"They represent perhaps the most extreme example of states privatising critical infrastructure but failing to extend protection."

Geostrategic cables

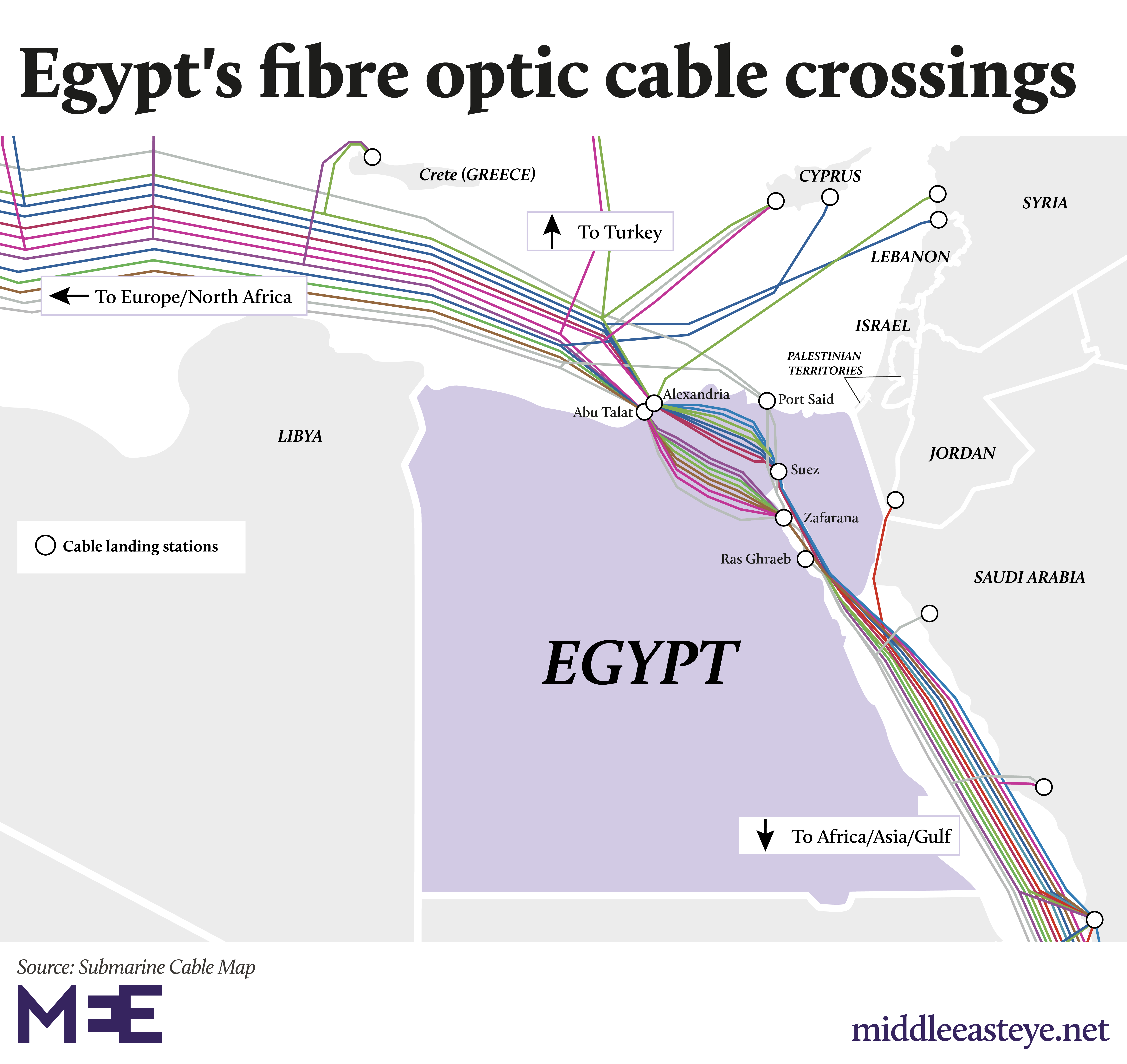

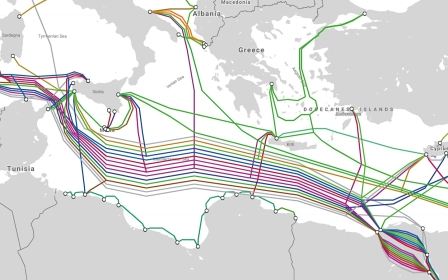

Between the Red Sea and Iran there are no terrestrial fibre optic cables crossing the Arabian peninsula. All internet traffic going from Europe to Asia either passes through the Caucuses and Iran, using the Europe Persia Express Gateway (EPEG), or via the far more congested Egyptian and Red Sea routes.

Egypt is a major chokepoint, handling traffic from Europe to the Middle East, Asia and Africa, and vice versa. The 15 cables that cross Egypt between the Mediterranean and Red seas handle between 17 percent to 30 percent of the world population’s internet traffic, or the data of 1.3 billion to 2.3 billion people.

Geography and politics has led to this particular set-up. “You cannot build a link through Syria or Iran due to the conflict and the political situation, and the war in Yemen takes out another terrestrial option, so [cables] take another path,” said Guy Zibi, founder of South African market research firm Xalam Analytics.

“There are only a few areas globally that are so highly strategic; the Red Sea is one of them, and in the African context, Djibouti.”

Most cables run under the sea, making the land crossing of Egypt more of an exception than the rule. Subsea cables are preferred as they are considered more secure, with greater vulnerability when cables hit land and then run terrestrially. “It is difficult to go under the sea and harm cables,” said Zibi.

The cables that run across Egypt and via the Suez Canal have logistical risks, such as breakages by anchors in the Suez’s shallow waters or from human interference.

“In 2013, three divers with hand tools cut the main cable connecting Egypt with Europe, reducing Egypt’s internet bandwidth by 60 percent,” said Karatzogianni.

The cables running through Egypt do not give the Egyptian state free rein to intercept data on behalf of the Five Eyes, however, despite the importance that President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, a former director of military intelligence, and his son, Mahmoud, the deputy head of the General Intelligence Directorate (GID), place on mass surveillance of Egyptian citizens.

“The Egyptians are superbly placed to have access [to data on the cables], but are not considered a trustworthy or stable partner. It is not where you want to put slick high-end [surveillance] equipment,” said Campbell.

Despite its strategic importance, Egypt is not part of any wider SIGINT networks. The Five Eyes alliance has information-sharing arrangements in place with some European countries and Japan and South Korea, for example, to intercept data from Russia and China. The NSA also has a relationship with Sweden, because it is a landing point for all cable traffic from Russia’s Baltic region.

By contrast, the US has less formal information-sharing relationships with a number of countries in the Middle East region including Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and the UAE.

“The Egyptians have an intelligence-sharing agreement [with the US], but they are probably quite supine in the relationship, being after the money [from the cable operators] and some intelligence sharing, which is largely [from the US side], ‘here’s what you get’,” said Hugh Miles, founder of Arab Digest, in Cairo.

Secret tapping

The Five Eyes could be tapping cables in Egypt or its territorial waters, however. Documents leaked by Edward Snowden in 2013 refer to a clandestine NSA base in the Middle East called DancingOasis, also referred to as DGO.

“It is extremely secret. Significantly it was built without [the host] government knowing, which is an immense risk to the Americans,” said Campbell. “Where it is located is pure guesswork. Candidate one is Jordan, then Saudi Arabia, and three, Egypt. Geographically the only other place would be Oman, from where Britain covers the Gulf.”

The cables connecting Europe, Africa and Asia run across Egypt and then down the Red Sea to the Bab el Mandeb strait between Yemen and Djibouti. The cables heading east veer off towards Oman. To the west of the capital Muscat is a GCHQ surveillance site in Seeb, with the code name Circuit.

“It is very close to where the submarine cables come in. Virtually all cables take a landfall between Seeb and Muscat. How convenient is that?” said Campbell.

For internet traffic to be tapped going from Oman to Europe, “the best option would be ultra-secret taps in the sea,” he added.

The Snowden leaks revealed that subsea taps are carried out by a specially converted submarine, the USS Jimmy Carter.

“There is a high degree of suspicion that American or other countries’ submarines use subsea platforms to intercept cables,” said Campbell.

A new cable for the region?

Israel is another country with the technical capability to tap subsea cables in the region, according to Campbell, though it currently has no connections to Middle Eastern networks.

There are no cables that go beyond the two coastal landing points of Tel Aviv and Haifa, which are connected to continental Europe and Cyprus.

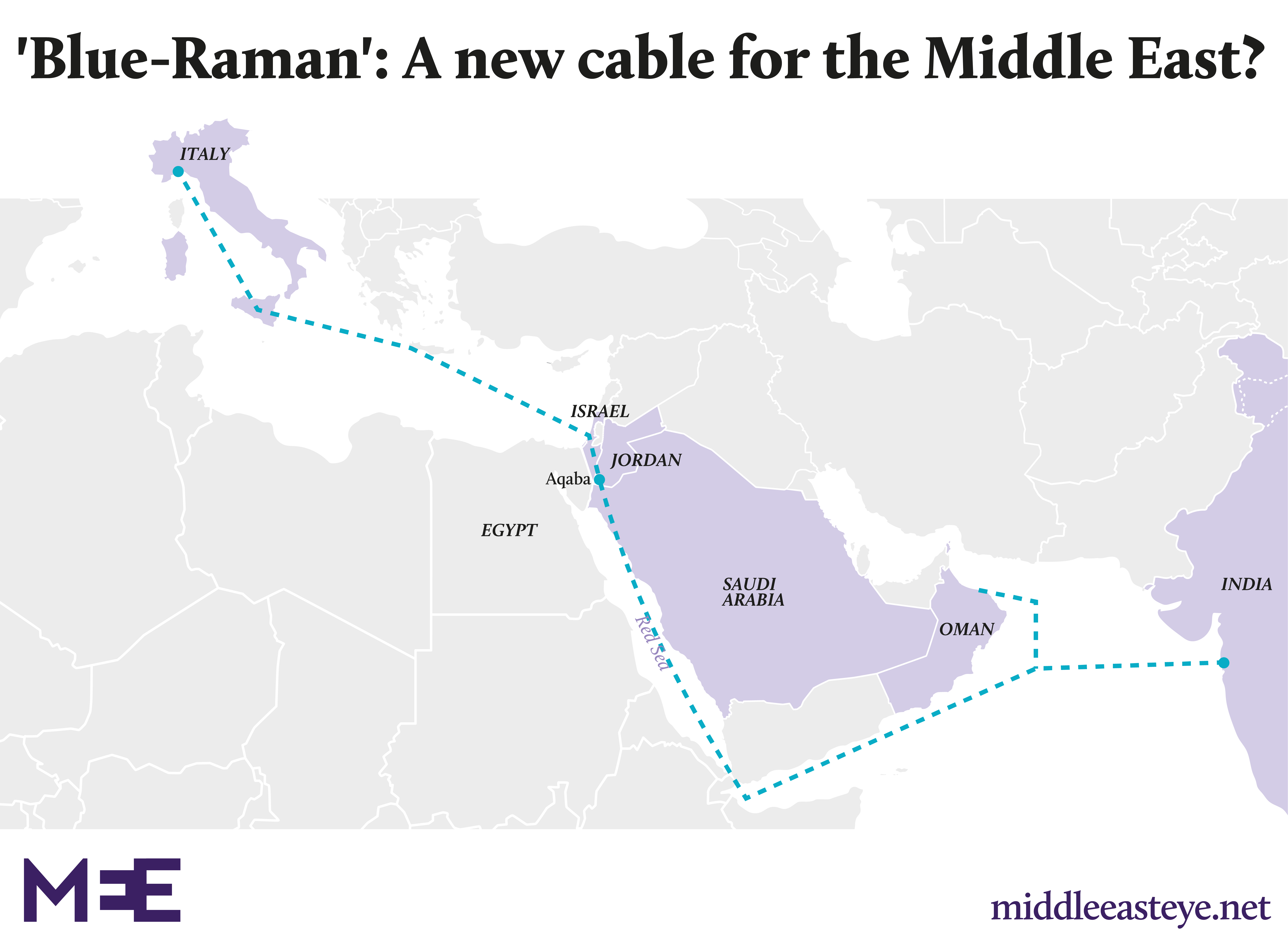

This could change if Google’s reported plans for its new “Blue-Raman” cable running from Europe to India through Israel, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and Oman come to fruition.

The cable is split in two, with the Blue part of the cable running from Italy to Aqaba on Jordan's Red Sea coast. The Raman cable runs from the Jordanian port south to Mumbai.

“As it is a Google cable, they know how to secure everything end-to-end. They will have built into their business plan the landfall at or near Tel Aviv, and will factor in that the Israelis will copy all data at the landing point, and encrypt against them. That doesn’t mean they [Israel] won’t take the traffic and see what they can get,” said Campbell.

It is not clear if the Blue-Raman cable will go ahead, seemingly dependent on a normalisation agreement between Saudi Arabia and Israel.

Google did not respond to Middle East Eye's queries about the reported project.

“If Saudi Arabia signs up to the deal with the Israelis, it will be a significant moment in geopolitics, where tech infrastructure - the fibre optic cable - becomes a facilitator for strategic collaboration between regional historical enemies,” said Karatzogianni.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.