Refugees in Greek legal limbo: 'I want to go back to Syria to die'

LESBOS, Greece - In an aging hotel outside the town of Mytilini, Mohammed wearily waits with his younger brother and their two heavily pregnant wives for updates on their asylum cases.

The group fled the violence in Sukhna, their remote desert hometown in eastern Syria - where family members were brutally killed by the Syrian government - first to Palmyra and then to Raqqa, as they tried to dodge the deadly fight between the Islamic State (IS) and rebel forces battling the army under air strikes.

The couples finally reached Lesbos after a dangerous journey by foot and car to the Turkish coast, making it onto one of the few boats that crossed the Mediterranean last summer.

That was months after the EU-Turkey deal took hold on 18 March, where the Greek government set up an accelerated border procedure so that authorities could send refugees back to Turkey.

Turkey is not a safe country

- Carlos Orjuela, a founder of Lesbos Legal Centre

According to this arrangement, Greece and the EU do not need to evaluate the individual protection needs of those arriving via the Aegean Sea, as Turkey is considered safe enough for the migrants to be relocated there.

That has left 30-year-old Mohammed, his brother and their wives in limbo.

"We escaped because there was no reason to live," he sighed. "The beheadings, the bombings. We sold everything to come here."

Their goal is to reach Malta, where they understand residents from Sukhna now work in construction, and the language is "similar to Arabic".

But their fearful dash has come to a halt. Trauma from the war they left behind has been compounded by the dangerous living conditions at the island's notorious Moria camp, including a deadly blaze that swept their living quarters last September.

Caught up in the asylum process, they finally moved into the ramshackle three-star hotel – taken over by an NGO – but the months of uncertainty has taken its toll. Mohammed, the family breadwinner, now says he wants to return home. "I want to go back to Syria to die. Anything is better than this."

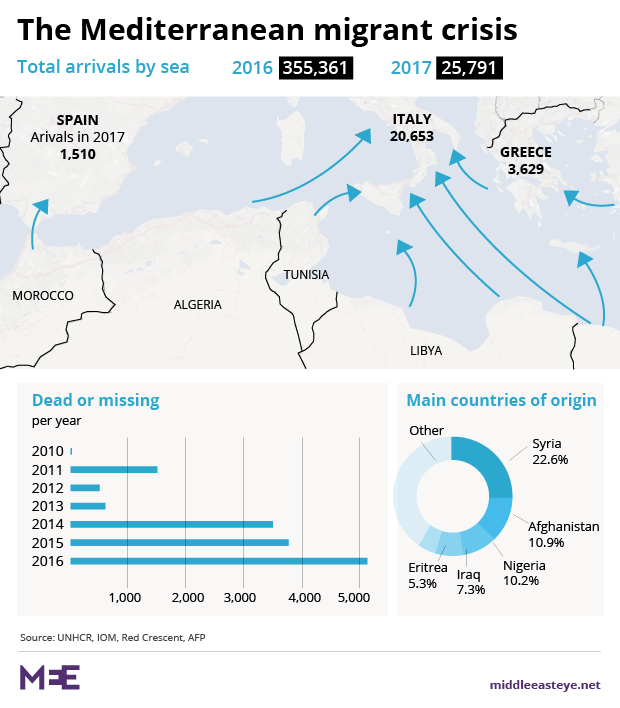

Migrants facing higher risk

According to the International Organisation of Migration (IOM), since the EU-Turkey agreement took hold, arrivals to Greece by sea have dwindled to 2,724 during the first nine weeks of the year, from over 134,000 in the same period last year.

But this has come at a deadly cost. Refugees are forced to take riskier journeys to reach Europe, like that through the Libyan desert and far more hazardous central Mediterranean Sea, and numbers have nearly doubled so far this year.

Others are at risk of deportation back to Turkey – and could potentially be pushed back to their countries of origin despite the threat of persecution - pending a final decision this month by the Greek high court.Greece's highest administrative court is poised to decide whether Turkey can be considered a "safe country" for refugees, after hearing a case relating to two Syrian asylum-seekers in Greece whose case may set a precedent that could potentially undermine the EU-Turkey exchange deal.

They have worked hard to survive and flee extreme environments like Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan - only to be broken by EU policy

- Declan Barry, doctor from MSF

"Everyone is extremely worried," says Carlos Orjuela, a founder of the Lesbos Legal Centre, whose team of volunteer Greek and international lawyers provide pro-bono services to the mostly anxious and confused refugees on the islands.

Orjuela says that asylum cases previously in legal limbo are now being rushed, lending to fears that refugees are on a fast track for being sent back to Turkey.

"Turkey is not a safe country," says Orjuela. "There is little access to information. Those sent back can be detained if they don't register, and won't know how to get a lawyer, or their rights," he said.

Mental health issues

Declan Barry, a doctor with the charity Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) working in mainland Greece and its islands, including Lesbos, believes the uncertainty surrounding the fate of refugees has had a severe impact on their mental health.

"They have worked hard to survive and flee extreme environments like Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan - only to be broken by EU policy," he says.

MSF has its hands full treating those suffering from chronic anxiety, post-traumatic stress syndrome, and even psychosis, he says. While one fifth of the refugee population required follow up treatment before the EU-Turkey deal, he estimates nearly 80 percent need psychological care now.

We need to accept more – Europe is rich

- Christina Chatzidakis, Lesbos community organiser

At the volunteer-run Pikpa refugee camp adjacent to the Lesbos airport and sea shore, with the Turkish coastline in plain view, those lucky enough to stay here are increasingly apprehensive.

Odey, a 34-year old electrician from Baghdad, is exhausted from his protective role guiding his wife and children in a now decades-long journey in exile. He first fled Iraq after the US invasion in 2004, when his father and brother were murdered by militia, and set up a home from scratch in Syria.

Over one decade later Odey is on the run from war again, this time trekking across mountains in Kurdistan – his 10-year old daughter injured running from a border patrol - and braving the sea to land arriving here 10 months ago. He quavers when he describes the protracted ordeal of waiting to hear if his family will be deported or not. "I feel sick," he says, embarrassed by his tears.

Unlike neighbouring island Chios, with its angry presence of the conservative, anti-immigrant group Golden Dawn, Lesbos has a historical tradition of left-wing politics and intellectual visitors.

"Turkey is not a safe place," retorts Christina Chatzidakis, an organiser part of the local community nominated for the Nobel Peace prize, for their dedication to helping the more than 800,000 refugees that have passed through, at a peak of 3,000 arrivals a day in 2015.

Chatzidakis says the island was overwhelmed with refugees then, but that barring those fleeing conflict is inhumane. "We need to accept more – Europe is rich. But there needs to be dignified procedure to bring them to Europe direct, not by boat," she says.

"As for stopping all this? We need to stop the war."

Mohammed's name is assumed to protect his identity.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.