Release of Saudi Ritz-Carlton detainees a PR move - but do investors even care?

WASHINGTON, DC - The release of three of the longest-held Saudi detainees rounded up in the Riyadh Ritz-Carlton in late 2017 was a PR push to rehabilitate the kingdom’s reputation among international investors, say analysts.

Critical foreign investment in the kingdom, key for the ambitious Vision 2030 economic reform plan set in motion with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s rise to power, has fallen in recent years.

'I think anyone who knows anything about Saudi Arabia looks at this and says, this was stupid, but it doesn’t tell us anything we didn’t already know'

- Kenneth Pollack, American Enterprise Institute

The high-profile arrests at the Ritz, a blazing diplomatic row between the kingdom and Canada last summer launched over a tweet and, most recently, the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi by a team of Saudi operatives on 2 October did little to help that situation.

But analysts say long-term investors will be far more concerned with the fine details of investment opportunities rather than optics, particularly as the events that have led to Riyadh’s reputational mess, even the killing of Khashoggi, are unlikely to have surprised them.

“I think anyone who knows anything about Saudi Arabia looks at [the Khashoggi affair] and says, this was stupid, but it doesn’t tell us anything we didn’t already know,” Kenneth Pollack, resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute think tank, told Middle East Eye.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Last week, Amr Dabbagh, businessman and former head of the Saudi Arabian General Investment Authority, and Hani Khoja, a former McKinsey consultant, were freed after 14 months.

Some of the last of over 200 royals and businessmen arrested to be let go, their release came just as the World Economic Forum, a strong Saudi delegation in attendance, kicked off in Davos.

A Saudi source told MEE last year that Dabbagh had been tortured, while the Wall Street Journal has reported that Khoja was repeatedly beaten in detention.

Then on Sunday, Mohammed al-Amoudi, a Saudi-Ethiopian tycoon, was released hours before the kingdom launched a bid to attract over $400bn to develop its mining, logistics and manufacturing sectors.

'The release of three businessmen may reassure foreign investors, but a lot needs to be done to alter the image of Saudi Arabia as a large detention centre'

- Madawi al-Rasheed, London School of Economics

The Saudi government contends that the detentions are a crackdown on rampant corruption in the kingdom, while critics have accused Mohammed bin Salman of using the guise of reform to consolidate his power.

Saudi authorities have not said publicly why the men were detained or released, nor have the men, now returned to their families, made public statements. It has been widely understood that many of the hundreds of other Saudis rounded up in the purge were let go once they agreed to hand over significant assets.

But politics also appears to have played a part.

Many of the crown prince's rivals were caught up in the 2017 purge, and a friend of one of the recently freed men, speaking on condition of anonymity, told MEE that they had been told to delete politically critical posts on social media about 10 days before the release.

Previously freed high-profile detainees have reportedly been monitored by bodyguards, forced to wear ankle bracelets and not allowed to talk freely to the media once they were released. And for some observers, the releases should do very little to ease concerns over the kingdom’s recent human rights record.

“Since 2 October, Saudi Arabia has had very bad publicity, starting with the murder of Khashoggi, to the detention of women activists and the news about their torture in prison,” said Madawi al-Rasheed, a Saudi professor and analyst at the London School of Economics.

“To diffuse the bad news, Mohammed bin Salman needs to project a positive image. The release of three businessmen may reassure foreign investors, but a lot needs to be done to alter the image of Saudi Arabia as a large detention centre.”

Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East and North Africa director at Human Rights Watch, accused the World Economic Forum last week of helping the Saudis “normalise a very abnormal, condemnation-worthy state of state affairs”.

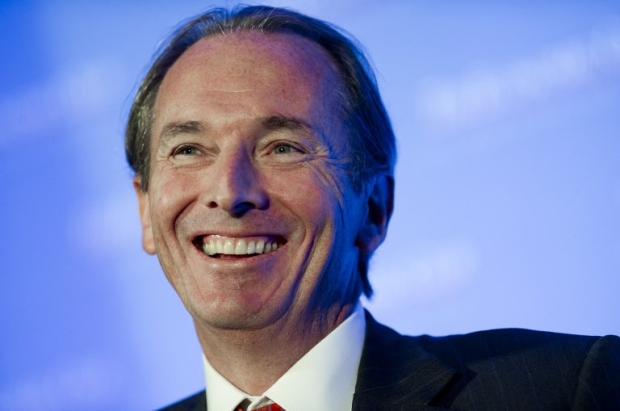

But others, like Morgan Stanley CEO James Gorman, who suggested at Davos that the Ritz detentions were one of the most creative and efficient ways of tackling corruption, don't necessarily see the purge as a problem.

Meanwhile many of those who have had trepidations about investing in the kingdom may well now be ready to continue doing business with Riyadh - if they ever truly lost interest.

Back in October, many high-profile executives made a big show of refusing to attend a major investment conference in Riyadh in the wake of Khashoggi's murder.

And though it certainly looked bad for the Saudi government, the no-shows didn't necessarily signal a loss in confidence in the kingdom's economic potential, said Rachel Ziemba an emerging market analyst and adjunct fellow at the Center for New American Security.

Rather, she said, it may have been that it was easier to bail on the conference than sell portfolio assets or cancel investments.

And beyond PR machinations, she said, it’s unclear whether the Ritz arrests or the Khashoggi affair are specifically to blame for the decline in foreign investment over the past year.

In fact, attracting foreign investment has been a problem for the kingdom long before it unveiled its Vision 2030 economic package, and investors' hesitation to commit to the Saudis may be more of a reflection that investors are – despite splashy tenders and glittery initiatives – still waiting for more details.

“Setting aside the political risks, there have been questions about what these terms will be. So there was some investment, but not a lot,” Ziemba said.

'I’m glad the detainees are coming out, but it’s also what’s the government doing with any assets that they might have seized'

- Rachel Ziemba, Center for New American Security

The question for those advising investors about the detainees, she said, will be less about reputational concerns and more about how the government is actually operating.

“I’m glad the detainees are coming out, but it’s also what the government is doing with any assets that they might have seized or might now be government assets,” Ziemba said.

“What is going to be the management of that? What has been the impact on private or individual wealth in Saudi Arabia? And what are the details and adjustments going forward?”

Pollack said his sense, speaking with Saudis, was not that there had been a wild outflow of corporate money, but rather more that Riyadh had anticipated more investment given legal reforms they have made based on feedback from investors.

Either way, he said, any expectations that this latest move will be the first of a long line of PR concessions from the Saudis should be tempered.

Parts of Washington have expressed severe frustration and disillusionment at some of the Saudis' recent missteps, and according to Pollack much of the attempts for PR rehabilitation have been aimed squarely at the US.

Yet that is likely to change, he said, following President Donald Trump’s tweet in late December declaring he would withdraw US troops from Syria. The tweet, Pollack said, made the Saudis “apoplectic”, who in their minds saw Trump ceding Syria to Iran and betraying a long-understood bond tying the relationship.

Fuelling their discontent was the fact that they had, at Trump's request, kept oil prices down at the OPEC meeting earlier in the month.

“As they understood it, the whole quid pro quo was ‘we’ll keep the price of oil low, but we need your help on Iran’,” Pollack said. “They’ve cooled off a little bit, but [US Secretary of State Mike] Pompeo’s trip really didn’t change their perspective.”

Now, said Pollack, the Saudis increasingly feel that they can’t count on Trump and will likely make moves, like the announcement earlier this month that they will further cut oil production, to signal their discontent.

The release of the detainees, he said, “was a PR stunt, but I think they are feeling that the PR isn’t as necessary as it was before Trump’s Syria tweet”.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.