Religious tensions simmer in Egypt's Minya

“Room 407? I am sorry, we called four different drivers, but no one wants to take you to Delga”. On the phone, the woman from the hotel reception desk sounds worried. Just a couple of hours before, she had assured me that the area outside Minya was safe. “But in Delga there are still problems, everyone is too scared to go there. We are Christians".

Delga is a remote town of 120,000 people on the southern outskirts of the Minya governorate, in Upper Egypt. It has had its relatively quiet way of life disrupted in recent years as revolutionary currents have swept through Egypt.

The violence reached one of its crescendos on 3 July last year as field marshal Abdel Fattah Sisi, who now looks all but certain to become Egypt’s next president, stepped in on the back of protests to remove former Muslim Brotherhood president Mohamed Morsi from power.

As the new military-backed authority was taking over the reins in Cairo, angry Muslim locals in Delga who claimed Christians were partially behind the coup d'etat began to attack churches and police stations.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Armed with machetes and guns, they took control of the town and drove police out, with some reports also suggesting that they imposed a historic protection tax levied on non-Muslims known the jizyah.

“Many Christian families were forced to flee” said the Coptic Catholic Bishop of Minya, Father Boutros.

Post-crackdown violence

A little more than a month after the events in Delga, religious tensions also spread to other parts of Egypt.

On 14 August 2013, while security forces dismantled the Rabaa sit-in in Cairo, killing some 600 Morsi supporters, assailants alleged to be enraged Islamists attacked churches and police stations across the country.

Security services and many Christians pointed the finger at Muslim Brotherhood supporters, but the brotherhood condemned the attacks and stressed that the perpetrators were not following any directions from its leadership.

Many Brotherhood supporters instead blamed what they call "baltagiya" or government thugs, who they said had been paid by the army to sow further mistrust of the movement.

Other parts of Minya suffered aside from Delga following the crackdown on the brotherhood.

“That day I went to church in the early morning to pray”, says Samira Aziz, a member of the al-Anba Mousa Coptic church in Minya. “At 7am the priest ran to tell us that there were clashes in Cairo and we had to leave.

“I went home with a friend, we shut the windows and waited there. We did not dare to look outside,” she adds, her voice cracking with emotion.

Several hours later, Aziz recalls, going downstairs and finding “many Christians from the Anglican Church crying, screaming, desperate as their church had been attacked”.

When we saw this "we ran to call our priest, only to find out that our church had been torched”, Samira recalls.

Normalcy returns

The security situation has improved over recent months, and security forces regained control of Delga last September. However, Boutros says a sense of stability has been slow to return to the area.

“The situation has improved and some families have returned to their houses, but it is not safe and our [Delga] priest lives here in Minya," says Boutros. “He only goes there on Sundays to celebrate mass”.

Sporadic attacks against police checkpoints and other targets continue, allegedly carried out by radical Islamist groups.

The turbulence is seen as pushing Egypt’s Coptic community closer to the army - while they once feared the military, they now turn to them for protection.

After the attacks, “people understand the real meaning of freedom” says Father Temesious, of the Coptic Orthodox bishopric. “They feel that the government is helping, more than before, to protect them”.

Many of Minya's Christians agree.

“I was one of the people who used to think that we need a civil president. But, well, at the moment Sisi represents strength and a vision,” says Michael Henari, a local Catholic man.

George, a friend of Henari who did not want to give his last name, nodded in approval.

“Sisi is a strong man”, he exclaims. "[Presidential candidate Hamdeen] Sabbahi is surely a revolutionary, and he’s not the right man for this period”.

In the Christian majority village of Bersha, home of one of the country’s oldest Coptic communities, it is clear who enjoys the most support. Sisi posters, which adorned swaths of Egypt in the lead-up to this week’s elections, are even more prominent here.

However, a taxi driver whose car is loaded with crosses and rosary beads still jokes about the one-sidedness of the campaign.

“What did you expect? Who’s the other candidate again?” he says.

2011 revolution

The state’s relationship with the Coptic community, which makes up around 10 percent of Egypt’s total population of some 80 million, has not always been clear cut. Copts often complain of institutional discrimination and socio-economic exclusion, although they are considered a relatively powerful minority and have a well-connected and large diaspora.

Before the 2011 overthrow of former strongman Hosni Mubarak, the Coptic community was seen as broadly allied with the regime despite some diverging points of view.

When the January 2011 revolution swept through Egypt, many saw it as a window of opportunity for Christians to rise up.

“Suddenly we could participate in demonstrations, raising our demands as citizens and not only as Christians”, explains Shenouda, a young Copt from Minya. (Ironically Shenouda is named after the late Orthodox Patriarch who for 30 years kept believers isolated from political activities, and who was accused by some of appeasing Mubarak.)

The next year or so, saw a mushrooming of political movements, groups and parties, as well as community marches through the streets in support of the revolutionary movement.

On 8 October 2011, Christian and Muslim demonstrators marched to the Maspero Television Building to protest the demolition of a church in Upper Egypt.

The army and security forces attacked them, opening fire at will. According to eye-testimonies and videos, army vehicles ran over the panicking demonstrators, crushing them to death. Before the night was over, 28 people had been killed. Among them Mina Daniel, the country’s most prominent Christian activist.

On the first anniversary of the killings, a large funeral procession gathered with Coptic girls and boys dressed as ancient Egyptians carrying candles and a big funerary boat. On the large sail, there were pictures of the 28 martyrs. Mina Daniel's portrait was right in the middle, and his bearded face and cliché-but-revolutionary long hair could be seen, clearly printed on hundreds of posters, masks, t-shirts. This time, however, the crowd marched in silence, without political slogans.

In front of them though, albeit at distance, Mina Daniel’s sister lead another march in tears. The first line of this parade was holding a long banner with the portraits of high-ranking military members to be held accountable. Chief among them was Sisi, with some protesters even holding dummies dressed in army robes with ropes tied around their necks.

Once they approached Maspero, a number of priests, including the future Pope Tawadros, gave funeral orations, although these never once mentioned the army.

On 8 October 2013, a few months after the army removed Morsi from power, no demonstrations were held for the Maspero massacre anniversary.

Trusting the army once again

The Coptic Church claims that it does not officially endorse one Egyptian political camp over another, but hints of strengthening ties are clear to see.

Back in 2012, Coptic authorities denied rumours that they were behind text messages backing Ahmed Shafiq, Mubarak’s last prime minister and Morsi's main challenger, but father Temesious admits that the church did choose to stand behind one man.

“There was a broad list of candidates, many of whom we did not like,” he says.

Coptic Orthodox Patriarch Tawadros II stood on Sisi’s side when Morsi’s removal was announced, and his portrait now appears with that of the Gran Muftì of al-Azhar, the highest religious authority for Egyptian Muslims, in some of Sisi’s electoral banners.

In March, Tawadros called Sisi “a hero” and his candidacy a “patriotic action”.

Temesious predicts that while the majority of Christians will vote for Sisi, “some young people will vote for Sabbahi as they did last time because they like the revolution”.

But “there are only two [candidates] and [they are] not very different. It would not be a tragedy for us if one or the other wins”, he says.

The revolution was an opportunity, but also a time of instability and insecurity, explains Temesious, “we started having a voice outside the church, and it will continue,” he says. “But we need to work with the government to do so”.

When asked if he trusts the army after Maspero, Temesious mumbles that “there were many things that seemed obvious, but now we don’t know if they are obvious. We don’t know what happened, we are not sure it was the army” who gave the order to crush and kill protesters, despite all evidence.

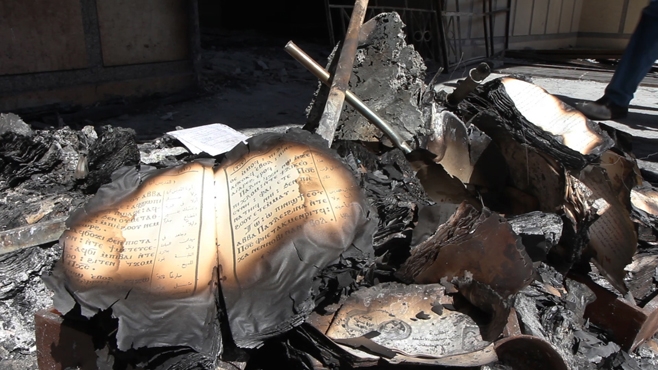

Temesious kindly escorts us to the door and to visit the church of Saint George, his parish which was torched on 14 August. “We are rebuilding it and we started holding celebrations here in February” he says happily.

To end our tour one of his followers, Bishoy, takes us to see the apse. Even though he regularly attends church activities, his eyes fill with pride and joy looking at the progress made. “We have to thank Sisi” Bishoy says, “because as minister of defense he immediately ordered the reconstruction of the church”. It is the army, he explains, that is paying for it. “They subcontracted it to a military construction company, that is why work is going so fast”.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.