The roots of Sisi’s support

Outside the government subsidised bakery that Mohamed Yousef manages in Sayeda Zeinab, a working-class Cairo district, a photoshopped family portrait of him with his child and presidential hopeful Abdel Fattah al-Sisi hangs on the wall.

In the photo, Yousef sits in the top left corner, with a solemn and contrived pose, without smiling. In the background, a red curtain drape blurs into a vertical Egyptian flag with the golden eagle symbol of the Republic. Pink ornamental flowers fill the empty space. On the two bottom corners, his son is shown in a glossy suit and bow-tie, first sitting with his legs crossed, then posing without the jacket, his hand on his hip. In the centre, bigger than everyone else and with a strained smile, stands Sisi in his military uniform.

“We love him. That is why I made the posters and hang them in the streets,” Yousef says.

Sisi has come to be known as Mushir (the field marshal) since he was placed at the forefront of the Egyptian army-led coup that deposed former president Mohamed Morsi on 3 July 2013. But relatively little is known of the man and even less of the candidate.

Although his campaign has published a manifesto, Sisi hasn’t appeared in a public rally and he has only addressed supporters via Skype from a control room in Cairo. According to Tarek Nour, chief advertising adviser for the campaign, his electoral platform is so “heavy with details [that it] will need a year for it to be explained to citizens.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Despite the lack of substantive details from Sisi’s camps, for many Egyptians, the army remains the most trusted national institution because of its involvement in the removal of both former presidents Hosni Mubarak and Morsi - and the emotional link between that history and their hopes for the future is solid.

“It was the military who always built Egypt and the one who keeps it. In this country the army is the factory of men,” explains Yousef.

“He does not have to announce his programme," he added. “We want someone who is powerful, not someone who just makes promises as Morsi did."

“Perhaps it is not necessary to make any real promises and to release them as a programme that people could put against him if he doesn't fulfil it. He has no real competitor, so it's logical to say as little as possible and to promise as little as possible”, says Michelle Dunne from the Carnegie Endowment, a Washington based thinktank on foreign policy.

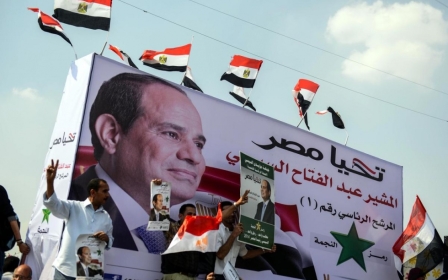

Custom-made support

Throughout Cairo and Egypt’s urban centres, people like Yousef and Hussein Ouba Abd al-Hamid have privately commissioned similar posters. Although these photoshopped pictures might appear slightly cheesy to an outsider, they are not considered tacky, but rather works of art, with graphic designers in working-class areas competing with each other to see who can blur more details together, using special effects and shiny glares.

“Sisi is the only one suitable to become president and bring stability to the country. He is a tough, strong, military man,” says el Hamid.

Posters run around $40 apiece, nearly as much as an average poor Egyptian makes in one month. To print four of them, a doctor working in a public hospital or a school teacher would have to spend his whole salary. Paying and commissioning them is regarded as a sign of wealth, importance and particular devotion.

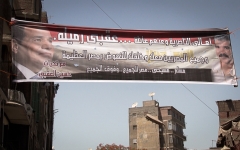

A few blocks down from Youssef’s bakery, Hussein Ouba Abd el Hamid, an employee in the Cairo Governorate, is sitting at a coffee place between two banners hanging over the street. To the left, there is a poster of Sisi in civilian clothes.

To the right, a man in his early 40s with a deep-black moustache is smiling from a second banner. “The Egyptian people, the family Ouba Ramilo, is with you [Sisi] and behind you in the resurrection of the great Egypt. Muslim, Christians: Egypt is for all and above all,” the banner reads.

“It is me” says el Hamid pointing at the posters, although it is quite hard to recognise him now with his greying hair. “It is an old picture of when he was younger” says a man sitting at the cafe with him. “He wanted to look good,” he adds chuckling.

“Sisi is the only one suitable to become president and bring stability to the country. He is a tough, strong, military man,” says el Hamid.

The frontrunner

Sisi is the frontrunner and does not need the support of local leaders like Yousef and Ouba. Still they hang pictures in the hope of being closely associated in the future with the man whom they expect to be the next president and strengthen stability.

“There are people who put their photos beside his because they love him sincerely,” explains Ramy Salah Eddin, a 32-year-old member of the Central Committee of Tamarrod.

“There are some others,” he adds, “who belong to the former regime of Mubarak and they dream of becoming members of the parliament by doing so."

Last year, Tamarrod collected millions of signatures for a petition calling for Morsi to be pushed out of office, and it allegedly has links to the military. The movement is now involved in the management of Sisi’s campaign: at the beginning of May, the Tamarrod office in Sayeda Zeinab became the district’s headquarter for Sisi and Ramy is the administrative responsible for the campaign in Cairo.

Ramy himself is not indifferent to what seems to be a new fashion across Egypt. The banners with his face and the portrait of the would-be president extensively cover areas of Cairo. “My case is special though, because I am from the Tamarrod movement, so it's normal that there is a connection between us and Sisi,” he says.

Former members of the movement who left in disagreement with the pro-military line or who split to support the other candidate Hamdeen Sabbahi, say that the special relationship between Sisi and Tamarrod could deepen after the elections.

Sisi does not have a party and Tamarrod, they say, could become his main political machine, much like what the National Democratic Party represented under Mubarak. For now, Tamarrod has announced that it will become a political party after the elections and it is using its name, network and structures to actively support Sisi’s official campaign.

“It is an unconventional campaign” Ramy admits, “but Sisi is a very unique man."

Tamarrod has organised campaign events in which it gathers at street corners projecting images of Egypt, the army and Sisi. Strobe lights and green lasers often complete the scenographic effect, while massive soundsystems blast thumping national songs and dance music played by “patriotic DJs”, as Ramy calls the young people who mix the music and run the show.

They also started a door-to-door campaign to hand out 300,000 energy-saving lightbulbs to people, a solution for continuous power cuts and energy crisis that plagued Morsi’s time in office and continue today. They are also, according to the central Electoral Commitee, a violation of the election law when passed out to potential voters.

“It is an unconventional campaign” Ramy admits, “but Sisi is a very unique man”.

He attributes Sisi’s few appearances in public to the candidate’s concern for the Egyptian public. “He is not afraid for himself, but for the Egyptian people because if there is a bomb, many innocents could die,” he said. Sisi has claimed in a televised speech to have survived two assassination attempts so far and a homemade bomb wounded three people at a Sisi supporters’ rally last Sunday.

Rallies and public meetings observed by the Middle East Eye were mostly deserted. At what was supposed to be “a big event” in front of the old presidential palace of Abdeen, in downtown Cairo, less than 200 supporters had showed up. A few streets away, interviewed people on the street said they had no interest in participating in a rally where Sisi’s place on stage was taken by pictures and representatives of Tamarrod.

Sisi’s campaign is “trying to reach out to people and rely on their enthusiasm,” Ramy says. Support for the general is so broad, he adds, that “we wouldn’t even need a real electoral campaign, but we rely on people because we don't have many funds.”

Tarek Nour, Sisi’s campaign manager and CEO of a communication company, however stated that around $1.7million have been spent so far in advertisement and conferences. The only other contender, Hamdeen Sabbahi, told the Middle East Eye that he only had $31,000 for his campaign.

Unofficial campaigns

Long before the general announced his intention to run, many other unofficial campaigns were launched.

Atief Zabalawy runs one in Gamaleya, the neighborhood of Cairo's Islamic City where the presidential hopeful was born and raised until the age of 25. Zabalawy’s cousins used to live in the same building as the Sisi when he was a child.

“But he didn't come to play with us. He was just watching from the window, as he was prohibited from playing in the street. [His family] was strict,” he recalls proudly.

The general never returned to the neighborhood after he left for his military career, but in the whole area, Sisi’s likeness is plastered in cafes, hung from streetlights, and taped inside car windows. Posters and images of Sisi compete with one another for some space on the walls of this dusty intersection of narrow streets.

On 30 June, as soon as Sisi urged Morsi to step down, Zabalawy started collecting signatures to ask the general to run for president. Soon after, he opened an office for his unofficial campaign to collect signatures, distribute pictures and feed the Sisi-mania with gadgets and other memorabilia.

Zabalawy’s support for Sisi resides in his military background and his credentials as a strongman.“It is enough that he got rid of the Muslim Brotherhood,” he says. “He removed a sword from Egypt's neck when he ousted them from power.”

“He will send his armies against slums, terrorism, the bad education and deteriorating health care in the country,” he says. “There are a lot of things in the country which need a strong man.”

When asked what solutions he thought Sisi had for these problems, he focused on the historic figures his and Sisi’s neighbourhood has produced.

“Gamaleya formed important people like Gamal Abdel Nasser, (literature Nobel Prize laureate) Naguib Mahfouz and (writer and intellectual) Taha Hussein,” he said. “Gamaleya is a factory of original, tough and powerful men.”

Michele Dunne of the Carnegie Endowment is not surprised by what seems, at times, to be support for Sisi without much tangible substantiation. “As an army general he has been a very obscure figure, very reluctant to speak in public, and people don't know his position about many things. People start to know him now a little bit but they don't have another real choice in the elections,” she says. “Hamdeen Sabahi is in a way doing a favor to Sisi in giving him the credibility of fair elections”, she adds.

Reham, a passionate volunteer of Sisi’s campaign seems to confirm this suspect. “I like the aura of mystery, that Sisi is a man of the military intelligence who thinks and works in silence,” she says.

Asked about what is Sisi’s vision for the country, she says, “I just know that he saved the country and I think that's enough. Egypt would have become Syria and Egypt is not Syria or Afghanistan.” But, she adds, “It’s true that nobody knows anything about him."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.