Why Ukrainian grain is not going to countries with a food crisis

It has been nearly two weeks since the first ship sailed from Odesa, carrying 26 tonnes of Ukrainian corn under the Russia-Ukraine deal brokered by Turkey and the United Nations.

The move was saluted as one that could alleviate the global food crisis and end hunger in poverty-stricken countries. Ukraine has some 20m tonnes of grain left over from last year's crop, while this year's wheat harvest is also estimated at 20m tonnes.

But rather than heading for the global south, the ships transporting corn and sunflower seed oil have been sailing to countries like Turkey, the UK, Ireland and China. Why is that?

'We don't decide where the cargo goes. It is a free market'

- Ukrainian official

A Ukrainian official with knowledge of the situation said that most of the ships carrying the cargo had been sitting in Odesa, Chornomorsk and Yuzhny since the start of the war in late February, adding that this was why they were carrying corn rather than wheat.

"The destination for the cargo has been negotiated between the supplier and the buyers, and they are totally commercial activities," the official said. "We don't decide where it goes. It is a free market."

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The official said the UN's World Food Programme would directly procure Ukrainian grain to be exported to global south and famine stricken countries.

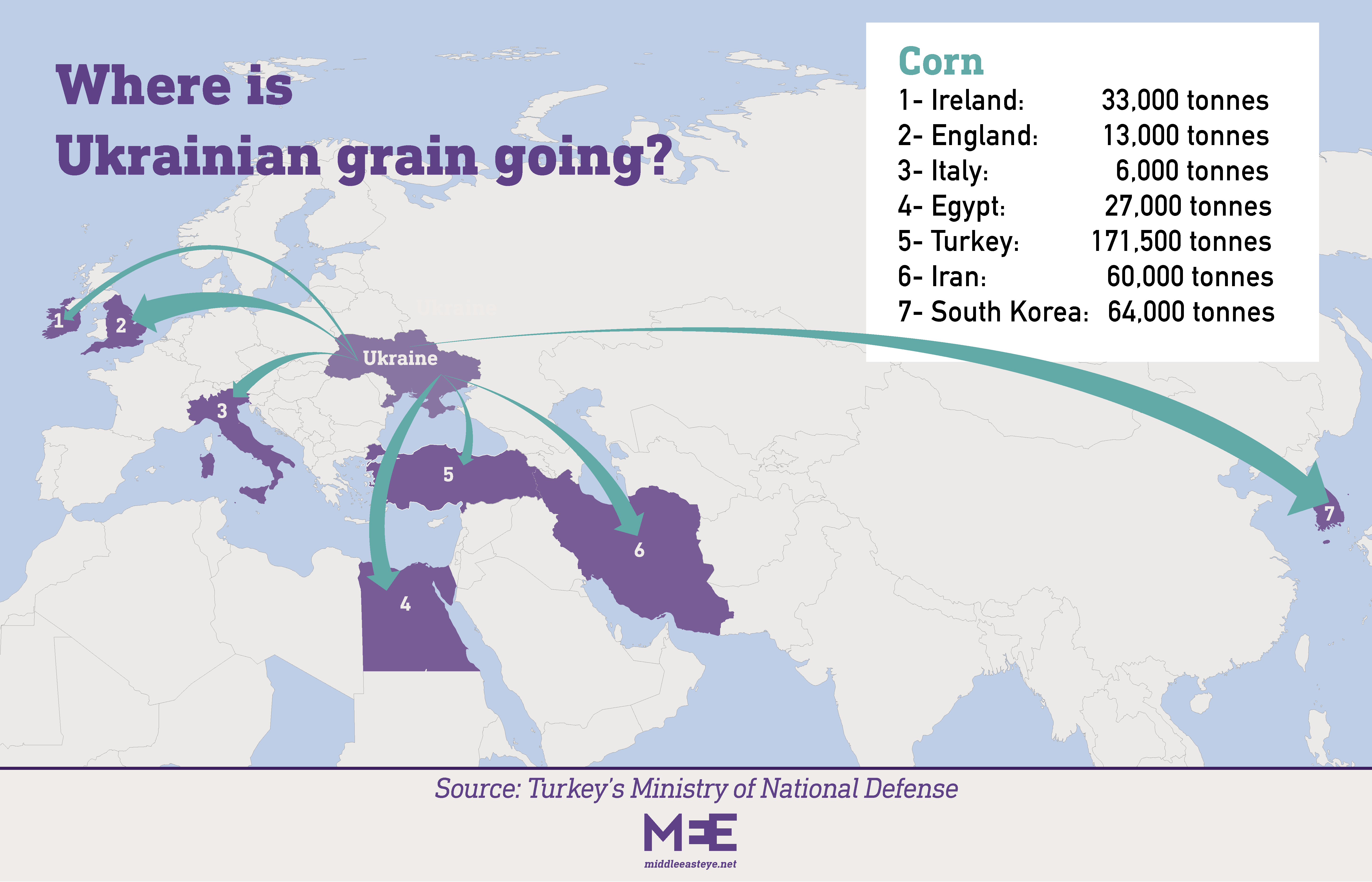

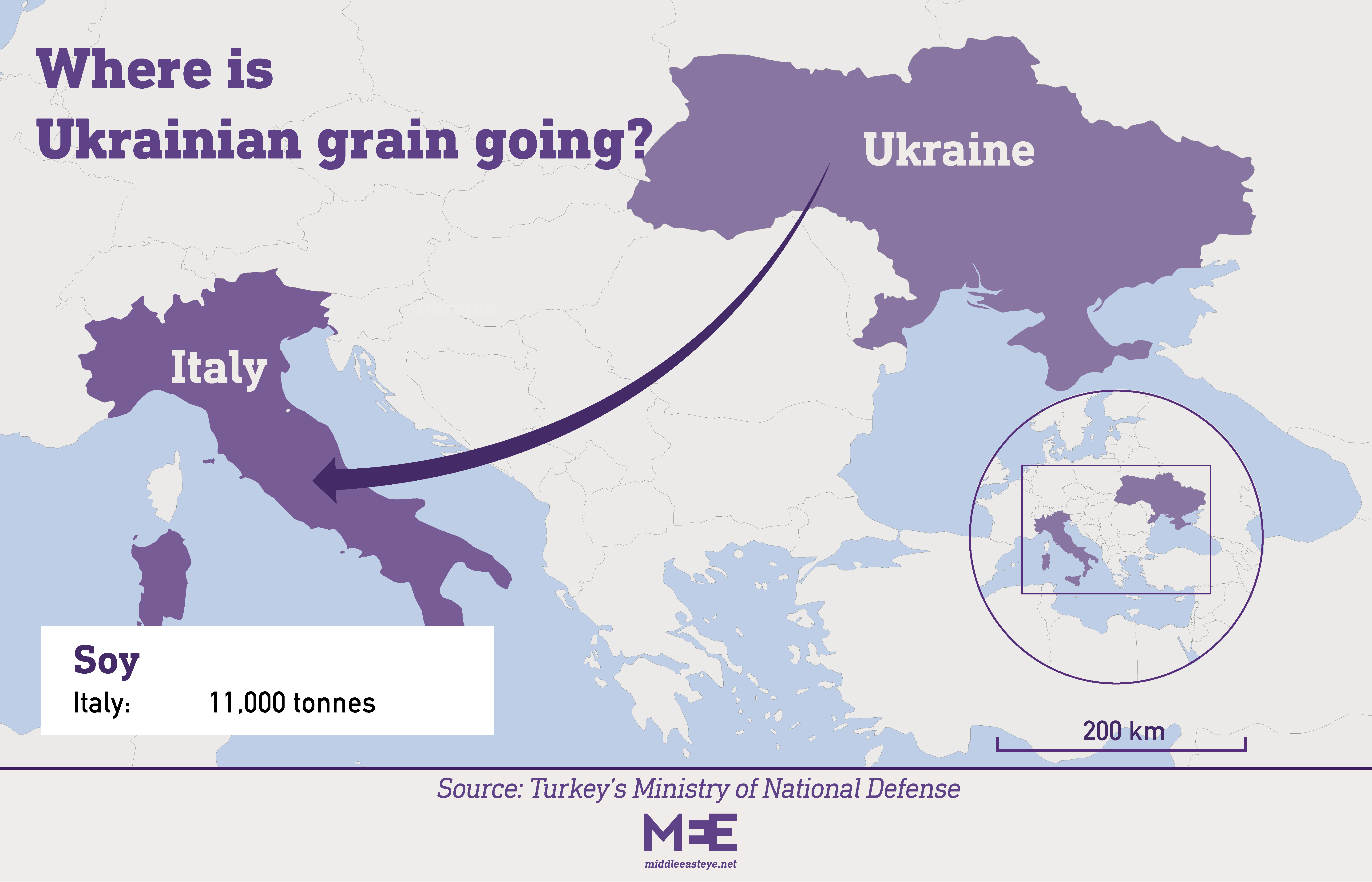

Twelve out of 18 ships that have been sitting in Ukrainian docks as well as four ships outside of Ukraine have so far carried 379,000 tonnes of corn, 6,000 tonnes of sunflower seed oil, 3,000 tonnes sunflower seed, 11,000 tonnes of soy and 50,300 tonnes of sunflower pulp, which is mostly used as animal food or fuel.

"A lot depends on what vessels - under which flags and with what contracts - we already have in the ports. And the priority is given to them," said Yevgeniya Gaber, a former Ukrainian adviser and a senior fellow at the Centre in Modern Turkish Studies at Carleton University, in Ottawa, Canada.

"Second, it is a technical issue of preparing documents. After five months of staying there, we have to make sure that they are valid, and the vessels are staffed. This affects the whole issue of formation of those convoys as well."

There were 2,000 seafarers from all over the world stranded in Ukrainian ports at the beginning of the war. That number is now believed to be under 450.

Gaber said most of the new ships that are coming out of Ukraine are heading to Turkey because security arrangements mean there is an expectation that Russia will not attack cargo carried to Turkey.

Data released by the Turkish defence ministry indicates that 171,500 tonnes of corn, more than half the amount of corn that has been exported, has been discharged in Turkey.

Vahit Kirisci, Turkey's agriculture minister, told journalists in June that Ankara was seeking a 25 percent discount on Ukrainian grain. A UN spokesperson, Stephane Dujarric, rejected the claim on Thursday during a press conference.

"We did much research, as much research as possible, and I can tell you that there was no discount built into the Black Sea Grain Initiative agreement that was signed in Istanbul," she said, referring to the Russia-Ukraine deal struck at the beginning of the month. "Furthermore, we are not aware of any other agreement that would guarantee such a discount."

However, Turkish sources maintain the view that a direct sale between the Ukrainian suppliers and buyers in Turkey may provide such a discount.

Turkey is grappling with soaring inflation as the conflict in Ukraine exacerbates the country's currency crisis. Food prices jumped by 91.6 percent in May, according to official data.

The Ukrainian official told MEE that Turkey has been given priority due to its role in brokering the grain deal.

"Yes, the cargo is initially full of corn due to the ships that have been sitting in the docks, and they aren't going to third world countries with a food crisis, but they already decreased the food prices, having an important impact," the official said.

Grain bought and then re-exported

Gaber said that most of the global buyers such as the UK, Ireland and Italy re-sell the imported grain cargo, meaning that it might end up in poorer countries.

"In the case of Turkey, for example, most of the grain Turkey buys in Ukraine, it is not for domestic consumption, it is for re-export to the Middle East and North Africa region," Gaber told MEE.

Reuters reported that the three ports involved in the deal have the combined capacity to ship around three million tonnes a month, and some expect this level of exports could potentially be achieved in October.

There is also a political dimension in play since there are suspicions that Russia has put pressure on countries in the region not to buy Ukrainian grain. "We have Russia there - Egypt just cancelled a huge contract with Ukraine after Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov's visit to Africa," Gaber said.

Other shipments are also sometimes renegotiated because they have spent five months in Ukrainian docks. Citing concerns over the quality of the grain due to the five-month delay in its shipment, a Lebanese buyer refused to take possession of the Razoni, which was the first ship to set off from a Ukrainian Black Sea port.

But the suppliers found a new buyer, and the ship will unload 1,500 tonnes of corn in Turkey, before going to Egypt with the rest of its cargo, which totals 27,000 tonnes.

Ahmed al-Fares, from the Ashram Maritime Agency, told MEE earlier this week that the number of ships going in and out of Ukraine was still low.

"The situation is not very good. Every week just two or three vessels are moving. The agreement is still not strong," he said.

Fares said ship owners will likely want to see higher freight rates and more guarantees before sending their ships into the Black Sea.

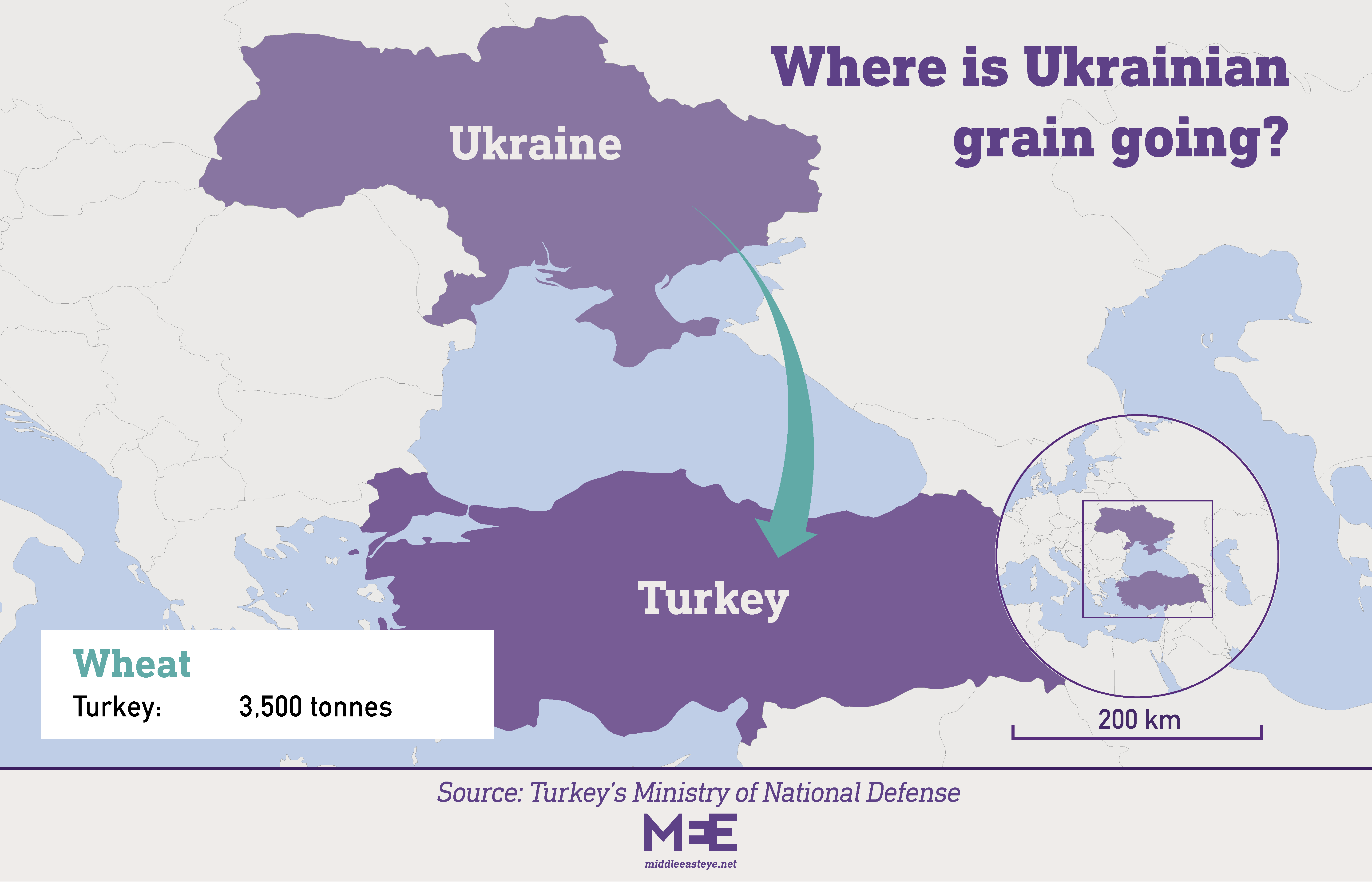

Wheat shipments also began on Friday, according to a statement from the Turkish defence ministry.

The Sormovksiy departed from Chornomorsk with 3,500 tonnes of wheat bound for Tekirdag, making Turkey the first buyer of wheat under the deal.

Reuters reported that insurer Lloyd's of London and broker Marsh launched a facility to provide up to $50m in cover for grain shipments from Ukraine. The cost of overall insurance for ships is likely to remain steep.

A joint coordination centre established by the Russia and Ukraine deal oversees the coordination of the ships that transport the grain. The centre is staffed by Turkey, Russia, Ukraine and the UN and so far it has worked without any major issue.

Turkish officials are hopeful that the deal can ease the global food crisis and also increase Turkey's standing as a mediator.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.