Safe houses in Saudi Arabia: Bangladeshi maids find refuge amid abuse, torture

Diplomats from Bangladesh have been forced to set up safe houses inside Saudi Arabia to protect hundreds of women who face sexual and physical abuse from employers in the kingdom, according to embassy cables leaked to Middle East Eye.

"Maids that have come to us have described being ill, overworked, facing verbal abuse and torture after they ran away from their employers and seek shelter at the safehouse," the diplomats said in their report to Dhaka.

In the memo, written in 2015, officials say that an average of three to four women per day sought refuge and requested for more resources at the shelters, including additional beds and CCTV.

The diplomats also appealed for a counsellor and note that the embassy has no female diplomats in the shelters to help the women.

Maids that have come to us have described being ill, overworked, facing verbal abuse, and torture after they ran away from their employers and seek shelter at the safehouse

- Bangladeshi embassy cable

Often the women do not have passports: the majority of Bangladeshi women who come to Saudi Arabia have their documentation taken away by their employers on arrival, meaning they have limited options to leave the kingdom if they chose to flee.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Employers often lodge complaints against their workers in Saudi courts, delaying their repatriation back to Bangladesh still further.

"It takes them 15 days to one month, sometimes three to six months, to prepare their paperwork to send them back home," the memo said. "Until then, they stay in the safe house."

The memo also noted that Bangladeshi diplomats needed to set up more safe houses across the Gulf country to keep up with demand as more women head for the kingdom to work due to an increased demand for domestic workers.

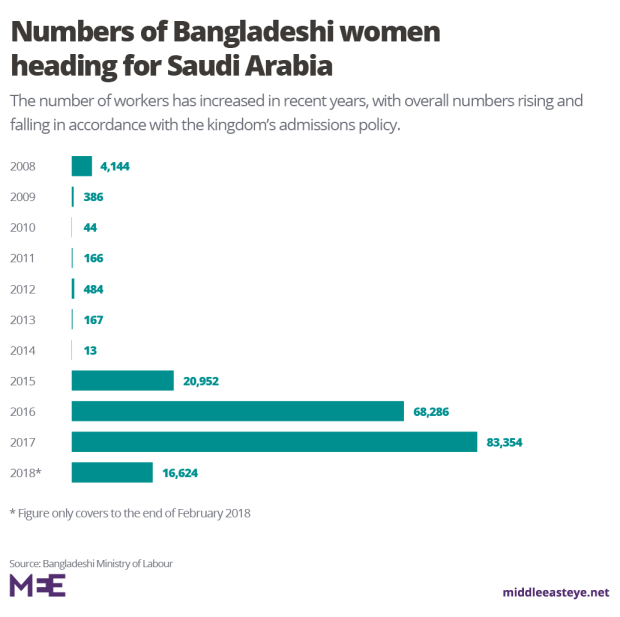

From 1 January until 28 February 2018, 16,624 women entered Saudi to work - just 4,000 less than the total for all of 2015.

The cable does not mention the current number of safe houses. But in 2017 it was reported that at least 250 women were using the facilities in Jeddah and Riyadh while they wait to be repatriated back to Bangladesh.

Middle East Eye asked the Bangladeshi Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Bengali ambassador inside Saudi Arabia for comment. It had yet to respond at time of publication.

'Women feel trapped inside'

Women who fled Saudi and lived in shelters before being repatriated back to Bangladesh have independently confirmed to MEE the existence of the homes.

Zobaida, a former maid who returned to Bangladesh from Saudi Arabia in March, told MEE in Dhaka that she knew of dozens of women who had gone to the shelters.

Like the hundreds of women who continue to be stuck inside the safehouse waiting to be processed, Zobaida stayed for three months before being allowed to leave.

"When I reached the safe house, more than 70 women were living inside the shelters, after escaping their bosses," said the mother of two, who added that she endured physical abuse at the hands of her Saudi employers.

"The Bangladeshi government had treated us well inside the safe houses, but many women feel trapped inside and just wanted to leave." The abuse described in the memo included women who had been beaten by their employers, not been paid for months and faced sexual harassment.

Rothna Begum, Human Rights Watch's woman researcher, who specialises in the rights of domestic worker in the Gulf, said that several countries who send domestic workers to Saudi Arabia had taken similar steps, including the Philippines and India, although several of these shelters are unofficial.

When I reached the safe house, more than 70 women were living inside the shelters, after escaping their bosses

- Zobaida, former domestic worker

"Many embassies of domestic workers have set up shelters usually within embassy grounds," Begum told MEE. "Shelters like this are essential as domestic workers who flee their employers can be arrested for 'absconding' as they have lost their legal status.

"Embassies should provide such workers with shelter, legal and medical assistance. Those that do not provide such shelter leave workers at risk of continued abuse by employers as they have nowhere to turn."

Some countries have banned their nationals from working in the Gulf. The Philippines, for example, stopped workers in January from heading to Kuwait, after Filipino President Rodrigo Duterte said that abuse had driven many maids from his country to suicide. Manila flew thousands of domestic workers home after a maid was found dead in an employer's freezer in Kuwait.

Since the ban, Duterte's administration has been in negotiations with the Kuwaiti authorities in a bid to create more safeguards for Filipino maids. But Begum said that a ban would harm rather than help workers who wish to migrate for work.

"Bangladesh should not ban workers from migrating to the Gulf but instead seek more effective protections for their workers from Gulf governments."

Arrival of more workers

The date of the memo coincides with lobbying efforts by the Bangladeshi government to repeal a prohibition on all male workers being given visas to work in the kingdom.

Riyadh introduced the ban in 2010 after local authorities noted irregularities and anomalies during the recruitment of Bengali expatriate workers.

Bangladesh's foreign affairs ministry said the ban had covered all workers except for female domestic workers.

The number of Bengali women working in the oil-rich kingdom rose from 13 in 2014 to 20,952 in 2015.

The number then tripled to 68,286, according to official Bangladeshi figures, after a request by the Saudi authorities that more be sent.

The memo noted that an "increase in female workers would pressure and encourage the Saudi authorities to allow Bengali men back into Saudi Arabia".

Bangladesh, which is one of the world's poorest countries, has an interest in its people working abroad: remittances sent home by expatriates are the second biggest source of income for its economy after the garment industry.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.