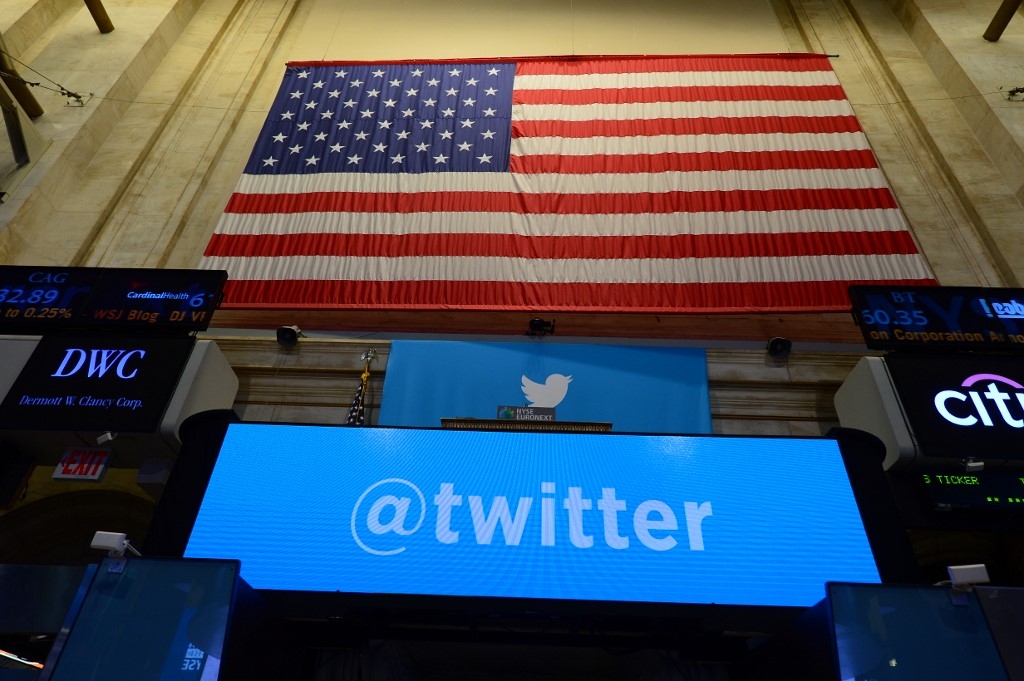

Saudi Twitter spies: How easy is it for government agents to spy on you online?

The recent case of three men accused of using staff positions at Twitter to spy on critics of the Saudi government has raised concerns among experts that the United States has inadequate cybercrime laws.

Emerson T Brooking, co-author of LikeWar: The Weaponization of Social Media, told Middle East Eye that US legislation has yet to catch up with the fast-growing threat of cyber espionage.

"There is not a law that can accurately describe what these individuals [allegedly] have done, because when the laws were written, no US corporation wielded such clear political influence," Brooking said.

On Wednesday, the US Justice Department announced that three Saudi citizens, including two former Twitter employees, obtained private, identifying information about Twitter users who were critical of the Saudi government.

Ali Alzabarah, Ahmad Abouammo and Ahmed Almutairi were charged with acting as illegal agents of a foreign government, which carries a maximum sentence of 10 years in prison.

Abouammo, who was arrested in Seattle on Tuesday, was also charged with destroying, altering, or falsifying records in a federal investigation, which carries a maximum sentence of 20 years.

Later on Friday, Magistrate Judge Paula McCandlis of the US District Court in Seattle granted Abouammo bond with travel restrictions while he awaited trial. But the ruling was stayed after prosecutors lodged an appeal, a spokeswoman for the US attorney's office for the Western District of Washington said in an email to Reuters..

Abouammo's lawyer, Chris Black, earlier said that an appeal would mean his client would remain in detention until a District Court judge made a ruling on McCandlis's decision.

Still, none of those charges are specific to the crimes, Brooking said, because the US has yet to create laws that fit their offences.

"Unfortunately, these laws do not distinguish between acts of theft or corporate sabotage and acts of a more clearly political nature," Brooking said.

Brooking said the US needs to reexamine laws regarding foreign agents so it can "formulate punishments equal to this sort of crime".

He also said that the Federal Trade Commission and other US regulatory agencies should pressure social media companies to strengthen their users' privacy.

"These individuals violated the privacy of hundreds of Twitter users; they have endangered the lives of dozens of human rights activists," Brooking said.

His warning is not hyperbole, as one can see in the case of the murder and dismemberment of journalist and Saudi government critic Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi embassy in Turkey last year.

A month after her his death, the CIA concluded that Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) had ordered the assassination.

In May, the Norwegian authorities placed pro-democracy activist Iyad Baghdadi in protective custody after the CIA warned of imminent Saudi government threats against him because of his criticism of MBS.

Those are just two of several documented cases in which rights activists have been targeted by the upper echelon of the Saudi government.

In 2017, Saud al-Qahtani, a former top adviser to the Saudi crown prince, who also served as the kingdom's director of cybersecurity, started circulating the "the_black_list" hashtag to target critics of the country.

"Does a pseudonym protect you from #the_black_list? No," al-Qahtani wrote on Twitter at the time.

Al-Qahtani's comments "give you an idea of how high [up] the chain cyber spying can get", said Ahmed Benchemsi, advocacy and communications director for Human Rights Watch's (HRW) Middle East and North Africa division.

'If the Saudis are able to call someone that gets inside information, you can kind of bet that every other government can too'

- Haroon Meer, founder of Thinkst

Benchemsi told MEE that HRW was "not surprised" by the recent cyber espionage charges.

In a 62-page report released on Thursday, HRW detailed scores of cases in which the Saudi government has used extreme methods of repression to silence critics, including those on social media.

"Saudi Arabia's targeting of critics has been a growing problem," the report said.

In addition to tracking social media profiles, HRW also documented cases in which Saudi Arabia hacked the phones of critics around the world, accessing cameras, microphones and personal emails.

"All of this tells you that Saudi dissidents are in big trouble, because their phones could be basically owned by Saudi security services," Benchemsi said.

'It's too big a problem'

Haroon Meer, the founder of Thinkst, an applied research company focused on information security, told MEE that "on the list of countries who you need to worry about, Saudi Arabia is not exactly high up in terms of technical sophistication".

"The fact that Saudi [Arabia] is doing it now is a good indication that the big players have been doing it forever," Meer told MEE.

The companies themselves can do more to protect users, if they choose to, including by implementing internal controls that make sure staff access to personal information is tracked and limited, Meer said.

The problem is whether companies are likely to put those protections up without a government mandate, since there are currently no federal laws in the US to protect the data users who agree to share with social media platforms.

Companies may be hesitant to establish stop-locks themselves, Meer said, because they take time and resources that could potentially slow other systems for Twitter and similar companies.

Even then, users' privacy isn't guaranteed.

"When you're tweeting, you've got to expect that the stuff you're tweeting is going to be seen," even if you are using a pseudonym, Meer said.

Even if social media companies were able to guarantee that their employees were not able to spy on users, there are plenty of other ways for governments to figure out who is behind any given Twitter handle, Meer said.

In the recent case of cyber espionage, working for the company allowed the alleged Saudi spies to go straight to the source, since, as Twitter employees, they had direct access to user information.

Without that sort of access, governments could still identify a user by monitoring traffic at the exact times the tweets in question are being sent out, and using those time sets to narrow down where a user's internet signal is originating from.

"What you'll start getting is smaller and smaller sets that overlap," Meer said.

"So maybe the first time you do it, there were 100,000 people online at the time the tweet went out. But how many of those 100,000 were also online at the exact time that the second tweet went out," and so on, until the set is narrowed down to one signal, he explained.

In the end, "you can't fully rely on Twitter to protect your privacy, because it's too big a problem", Meer said.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.