Snipers and speed cameras: The perilous road from Damascus

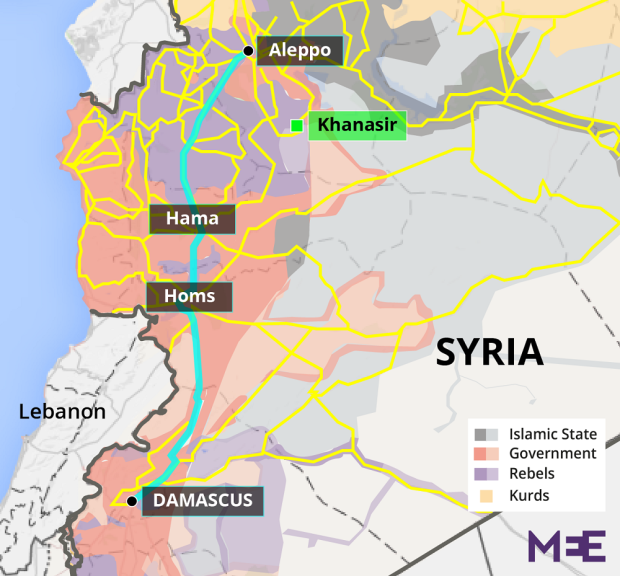

ALEPPO, Syria - What used to be a four-hour drive from Damascus to Aleppo is now an eight-hour slog that runs for more than 160 km through opposition-held territory, with the Islamic State (IS) controlling one side of the road and the Nusra Front, Syria’s al-Qaeda affiliate, the other.

The road - a lifeline for food and medical supplies to the government-held part of war-torn Aleppo - is kept open by the Syrian Arab Army (SAA), who man checkpoints overseen by portraits of President Bashar al-Assad and the national flag that line much of the road.

After the bombed-out shell of the central city of Homs, half of which lies in ruins after years of fighting between the government and more moderate rebel groups, the main road is closed. After this point, the road runs through opposition-held territory, and a four-hour diversion snakes through countryside under Syrian government control.

As the terrain becomes more barren, any slight hill or rocky outcrop on the flat landscape has been turned into a military outpost, where machine guns poke out over the low turrets of sandbanks.

“There is no ceasefire here as the terrorist groups Daesh [IS] and Nusra are not included,” the SAA commander of the al-Salamiya area told MEE, speaking on condition of anonymity.

A landmark truce was agreed in late February, which brought a much-needed reprieve to large parts of Syria, although in recent days that too seems to be faltering, especially in the north and near Aleppo that has seen a serious uptick in violence.

From a converted farm in the heart of enemy territory, Salamiya heads military operations to beat back attacks from opposition forces - a constant threat to drivers and SAA personnel - and keep the road open.

“Daesh are always trying to close this road because it is the only route to Aleppo - a lifeline to the city - so if they manage to close it, they cut Aleppo off from all government supplies,” he said.

Although IS and Nusra have clashed on other battlefronts in Syria, along these stretches of roadside territory, the commander said they were “like brothers” who regularly co-ordinated attacks, launched simultaneously from either side of the road.

“The situation is very tense and we have to be constantly alert. They may attack at any time,” he said, while looking at a map on the wall and outlining enemy positions that rest terrifyingly close to his small base.

The last major battle - which sealed off the road for a week - was at the end of February, when Nusra and IS launched an assault on the town of Khanaser, some 50 kilometres from Aleppo that raged even as the US and Russia were brokering Syria’s ceasefire, which excludes internationally designated terrorist organisations, including IS and Nusra. The SAA eventually forced the militants to retreat but there were reportedly extensive losses on both sides.

The commander claimed his units had killed about 170 IS militants and a further 20 of their leaders.

“Daesh are weaker than before, a lot weaker, and their morale is dropping,” he said confidently.

'Abu Ali Putin'

While Moscow announced in March that it would seriously de-escalate Russia's almost six-month aerial campaign in Syria in support of Assad, operations on this contested stretch of road continue to be boosted by ongoing Russian aerial bombardment.

The support seems to be backed up by British MP David Davis who recently visited Syria as part of a fact-finding mission and said that Assad told him that Russian President Vladimir Putin had pledged to “not let you [Assad] lose” even after he agreed to pull out some of his troops.

The commander says that the Russia support has been critical.

“Even now, the Russians are still helping us, they are our friends,” he said, laughingly adding that the SAA nicknamed the Russian President “Abu Ali Putin”.

But he admitted that ground operations against the militants in the area were now at a standstill, while his units waited for reinforcements.

“There is no imminent solution here and I expect we will be fighting for a long time but we are prepared for that, and we will fight them until the very last man,” he said. “We have been fighting here for five years and, if necessary, we will fight for another five years. There can be no political solution with Nusra and Daesh, only a military solution.”

But stretches of the road are too dangerous even for the army checkpoints and these must be driven at speed and only in daylight. “There are some places where no-one is really in control,” said one motorist who regularly drives the road. “From late in the afternoon, if you have a problem, no-one will stop to help you,” he said. “Nusra are so close in some places, you can see occupied villages from the road, and IS territory is just 10 kilometres to the west. It is extremely dangerous.”

Motorists also remained under constant threat from IEDs, the commander said, explaining that opposition forces took advantage of night-time and bad weather, when SAA forces were unable to monitor the landscape, to plant bombs along the roadside.

Despite the risks, drivers continue to brave the road, grateful for the access it provides. Its closure crippled daily life in Aleppo - already difficult - stopping vital aid reaching the city’s residents, including hundreds of thousands living as internally displaced people, many of whom rely on such assistance to eat.

It also kept friends and relatives apart and two years ago, when the road was sealed off completely, Syrian singer Housaam Junaid penned a now-popular ballad about being unable to reach his lover in the besieged city that has been ravaged by government bombing and rebel shelling for years.

Since 2012, Aleppo has been a divided city, half ruled by the government and its allies, and half by a coalition of opposition forces that range from the Free Syrian Army to groups like Nusra. Getting enough supplies in has long been a challenge for both sides, with pro-government forces coming very close to cutting the last main rebel supply line from the north before the ceasefire was agreed. As the fighting has returned, so too has concern that the access will be cut once and for all.

Lorries loaded with goods heading to Aleppo from Damascus trundle past the rusting debris of the battles that have torn open Syria’s landscape, including the now shelled-out carcass of Khanaser.

Nearby, the road runs alongside the vast al-Jaboul salt lakes, which used to supply the whole of Syria with salt. With the far shores of the lake lying in the province of Raqqa - IS’s Syria stronghold, the lakes are now deserted expanses, where salt has not been gathered for years.

Speed cameras

The drive is post-apocalyptic, with each passing humble roadside village abandoned, and there is nowhere motorists can safely stop. Even deserted and destroyed villages, where the pointed clay domes of traditional homes have been shattered by shelling and clashes, conceal the hidden danger of still being rigged with explosives. A month ago, an elderly couple was killed when they entered one deserted building to relieve themselves and triggered an IED.

Passing motorists and SAA soldiers are not the only ones sandwiched between IS and Nusra. Brave electricians have started work on repairing the power supply along parts of the road, where charred pylons are folded in half and the few cables that have not been stolen are left trailing on the ground.

However unstable the barren central section of the road to Aleppo remains, at either end, life goes on. Cameras around Damascus snap speeding motorists, and the $100 fine - incongruous in a country where conflict rages on multiple front lines and sanctions have ravaged the economy - is very high.

On the outskirts of Homs, local people stand outside war-scarred buildings to watch a funeral cavalcade of hundreds of vehicles, driving two abreast, taking up the whole road. Soldiers crammed into civilian cars fire Kalashnikovs into the air, through passenger windows and from the back of pick-up trucks, to inform local people that the funeral procession of an important military general is on its way.

Killed fighting on the frontline at the ancient city of Palmyra in southern Syria - the day before the SAA declared its hard-won victory and finally drove IS militants from the city - General Shaban al-Oja was highly respected. Oil-smeared mechanics, elderly women with traditional facial tattoos and children standing on walls watch the cavalcade in respectful silence.

At the other end of the road, as it nears Aleppo, villagers plant crops in the spring sunshine and herd modest flocks of sheep and goats. But the entrance to the city, where sandbanks and makeshift walls of rusting oil barrels protect motorists from the sights of snipers, acts as a reminder that behind these veneers of normality, the Syrian conflict stumbles on.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.