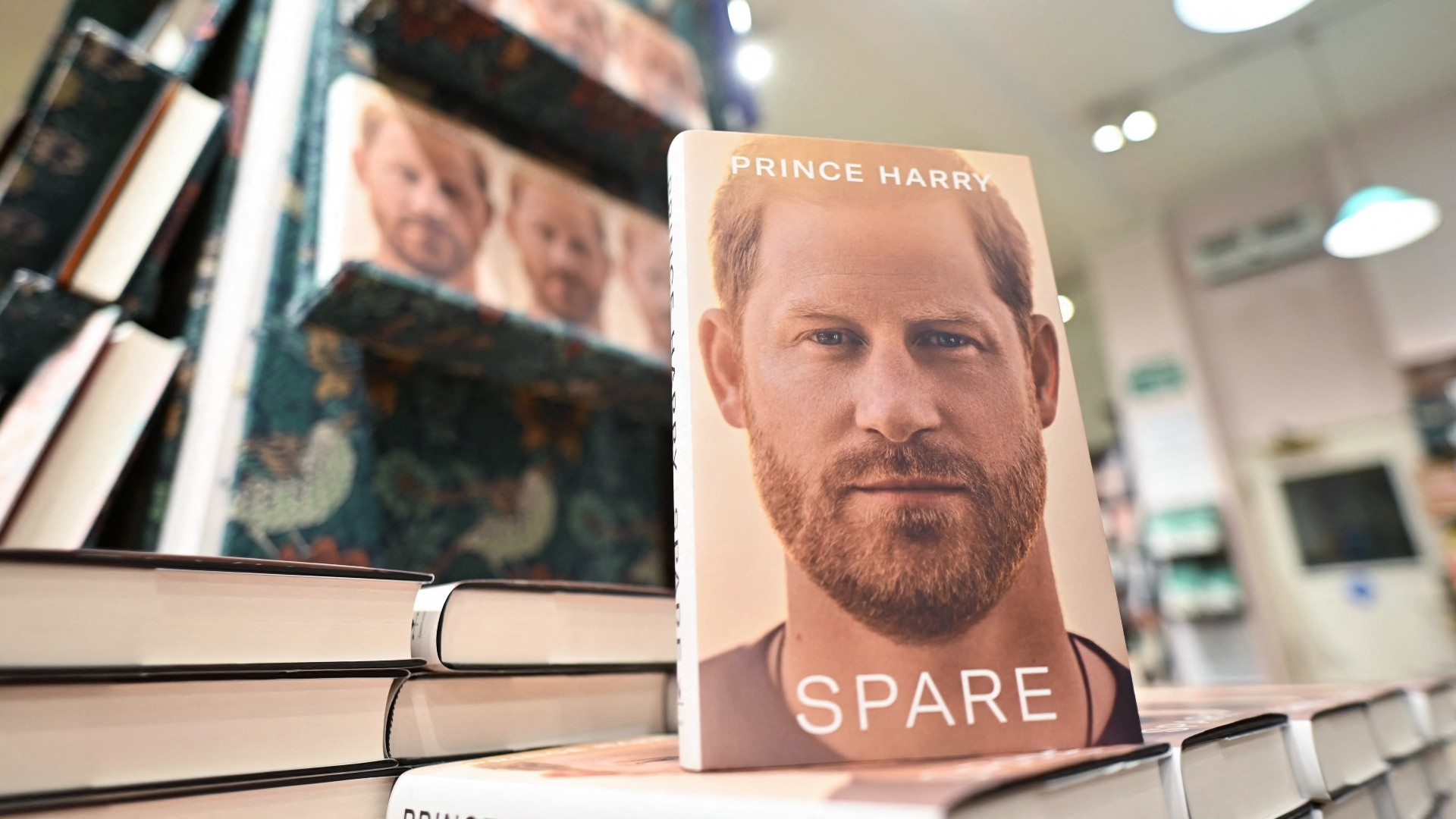

Prince Harry's Spare: Fighting for a 'Christian army', Muslim baby taunts and other takeaways

Prince Harry's revelation that he killed 25 people in Afghanistan drew headlines and condemnation ahead of the publication of his memoir Spare on Tuesday, with the newly released book offering more problematic insights into his time in the military.

The disaffected royal details how he was fed the narrative of fighting for a "Christian army" during his training for deployment in Iraq, and many of his anecdotes and language are uncomfortable and jarring, particularly from a self-described anti-racist.

Harry describes being emotionally volatile, bored and looking for a purpose in his life, with the army seemingly giving him a sense of direction. He draws a comparison between the paparazzi that plagued him and Iraqis in the chaotic period following the US-led invasion.

'Your mother was pregnant when she died, eh? With your sibling? A Muslim baby!'

- Prince Harry

The paparazzi had always been "grotesque people", and as he grew older, they had grown "more emboldened, more radicalized, just as young men in Iraq had been radicalized," Harry writes. "Their mullahs were editors."

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The chance to escape to the military and the discipline it offered was a pull factor that maybe could help him "snap me out of it", he recounts.

Sent to train as a helicopter pilot in the US, "I became more fluid with the Apache, more lethal with its missiles. More at home in the dust. I blew up a lot of cacti. I wish I could say it wasn't fun," he says.

'Christian army'

One scenario that Harry recalls having to act out in a training exercise before his planned deployment to Iraq was fighting as part of a "Christian army".

"We'd been given a meta-narrative, which we now recalled: We were a Christian army, fighting a militia sympathetic to Muslims," he writes.

Harry makes no mention of his views on the wars in Iraq or Afghanistan, despite going to great pains to talk about his unconscious bias on issues surrounding race and his concerted effort to work on it.

In describing his military training, he muses that "much of what they did to us was illegal under the rules of the Geneva Conventions, which was the whole point".

Amid sleep deprivation, staged kidnappings, being blindfolded and deprived of food and water, his mother's relationship with Dodi al-Fayed, son of renowned Egyptian businessman Mohamed al-Fayed, is weaponised against him.

Harry recounts how a woman wearing a keffiyeh-type scarf tested his psychological preparedness by speaking about Princess Diana's relationship with al-Fayed. The two died in a car crash in Paris in 1997, with unsubstantiated rumours circulating that she was pregnant with al-Fayed's child.

"Your mother was pregnant when she died, eh? With your sibling? A Muslim baby!" Harry recounts the woman saying. His training required him to remain unfazed, but he writes he "screamed at her with my eyes" as someone else spat in his face.

'Guilt about not being at war'

In 2007, the British army announced that the 23-year-old Harry would be sent to Iraq to fight. "It was official. I was off to war," says Harry.

Shortly after the announcement, however, Harry's deployment was called off. It became clear that Iraqis fighting the British and American occupation would target him in a bid to achieve a major propaganda victory.

"The mission had simply become too dangerous, for me, for anyone who might have the bad luck to be standing next to me. I'd become…a 'bullet magnet'," writes Harry. "I was crushed."

'Children throwing rocks was about all the Taliban had in the way of anti-aircraft capability'

- Prince Harry

Undaunted by the idea of war, Harry again sought to be deployed somewhere else. "Libya was heating up, though. How about that?" he recalls asking his superiors. The request was quickly declined.

With his tour in Iraq prematurely over, Harry turned to the consumption of copious amounts of alcohol, particularly Southern Comfort and sambuca, to deal "with unsorted anger, and guilt about not being at war - not leading my lads".

Harry recalls telling his commander that unless he was sent back to a conflict area, he would "have to quit the army".

"A prince in the ranks was a big public-relations asset, a powerful recruiting tool. He couldn't ignore the fact that, if I bolted, his superiors might blame him, and their superiors too, and up the chain it might go," Harry says. At the time, the British media published several images of Prince Harry in relaxed and heroic military settings.

'PlayStation game'

Harry was finally given a role as forward air controller (FAC) in Afghanistan's southern province of Helmand, guiding fighter jets towards suspected Taliban targets. This time in secret.

As the British army sought to manage the risks of having such a high-value personality amidst its ranks, a bored Harry - deployed safely away from the frontlines - yearned to see more action.

"If there's anything duller than watching paint dry, it's watching desert," Harry thought.

Eventually, Harry was deployed to a frontline outpost at an abandoned school, which had either been an agricultural university or a madrassa. For Harry, it was now a small "part of the British Commonwealth".

In his role as an FAC, Harry recalls wanting to use an almost one-tonne bomb on his first attempted air strike on a suspected Taliban position, which even his American counterparts saw as too much, something he jokingly thought as "very un-American".

During his tour of Afghanistan, Harry also flew Apache helicopters. He recalls that children could easily throw rocks at them while flying at low altitudes.

"Which they did all the time. Children throwing rocks was about all the Taliban had in the way of anti-aircraft capability," he remarks.

In Afghanistan, Harry says he killed 25 people, who he says were Taliban fighters, while flying Apache helicopters. "It wasn't a number that gave me any satisfaction. But neither was it a number that made me feel ashamed," says Harry.

In 2013, Harry compared being an Apache gunner to playing video games, and he does the same in Spare: "The thumbstick I fired was remarkably similar to the thumbstick for the PlayStation game I'd just been playing."

The Taliban, which returned to power in Afghanistan in 2021 after the US-UK pullout, has condemned the prince's remarks.

"The western occupation of Afghanistan is truly an odious moment in human history and comments by Prince Harry is a microcosm of the trauma experienced by Afghans at the hands of occupation forces who murdered innocents without any accountability," Abdul Qahar Balkhi, spokesperson for the Taliban-led Afghan foreign ministry, said.

In Spare, which was ghostwritten by the American author JR Moehringer, the prince describes the 9/11 attacks on New York as one of the reasons for him not feeling guilt over the fighters he killed.

While in combat, Harry didn't view his victims as "people". Instead, they were "chess pieces removed from the board," he said, adding: "I'd been trained to 'other-ize' them, trained well."

When Harry's cover in Afghanistan was also eventually blown, and he had to make his way back to the UK, he contrasts his sadness at leaving the war zone with the glee of other soldiers who are only too happy to go home.

"They were all jubilant. Going home. I stared at the ground," he writes.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.