Sudan's attempts to boost Hemeti's reputation aren't going to plan

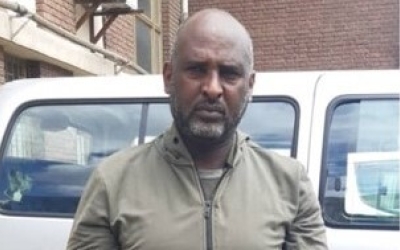

When Mohamed Hamdan Daglo, the paramilitary leader better known as Hemeti, was named Sudan's human rights defender of the year last month, eyebrows were raised.

Hemeti is the second-most powerful man in Sudan and head of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a paramilitary born from the notorious Janjaweed militia accused of atrocities in Darfur, South Kurdofan and Blue Nile State. Under his leadership, the RSF has also played a key role in the 2021 military coup and repeated (sometimes deadly) crackdowns on pro-democracy protesters.

The irony was hard to miss. But to his critics, the award was just the latest example of Hemeti's attempt to improve his reputation this year. And he's spending big.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Not all his attempt to win hearts and minds, both at home and abroad, are going exactly as planned, however.

During the World Cup, Hemeti opened clubs across the country allowing Sudanese in deprived neighbourhoods to watch the games for free.

But the venues remained largely quiet, with the pro-democracy Resistance Committee activist groups calling on Sudanese to boycott the attempt to curry favour and warning the government against interfering in sports.

Other initiatives have similarly fallen flat. If 2022 was supposed to be the year Hemeti won legitimacy, there's still some way to go in 2023.

Darfur implications

In the camps for people displaced by the conflict in Darfur, which Hemeti is accused of playing a leading role in, the paramilitary leader's award was met with disbelief.

Adam Rigal, a spokesperson for the Darfur displacement camps, condemned the National Human Rights Commission's decision.

"This is clear fraud and cheating. How can the abuser become the defender? This award is very painful for us as victims of war, people still stranded in the camps or seeking refuge worldwide," Rigal told Middle East Eye.

"RSF violations are still ongoing. Four million people are still in the camps, the militias are attacking civilians every day in the region, the situation is getting worse every day. What the commission did is treason."

'How can the abuser become the defender? This award is very painful for us as victims of war'

- Adam Rigal, Darfur camps spokesperson

Similarly, Mossad Mohamed Ali, a prominent human rights defender and director of the African Centre for Justice and Peace Studies (ACJPS), noted that under international law human rights defenders "are individuals or groups who act to promote, protect or strive for the protection and realisation of human rights and fundamental freedoms through peaceful means".

"Based on this definition, Hemeti cannot be considered a human rights defender simply because he is the head of the state that violates the rights of its people on a daily basis.

"As head of state and as a leader of the armed forces and RSF, he is involved in widespread and systematic crimes against international human rights law, such as extrajudicial killings, torture and the arbitrary arrest of human rights defenders and political activists," Ali told Middle East Eye.

He noted that the National Human Rights Commission is not independent and up to international standards. "In one word: this commission lacks credibility," he added.

World Cup watching

Another attempt to rally support that appears to have misfired was the "Daglo initiative for free viewing of the World Cup".

In impoverished neighbourhoods in Khartoum and elsewhere, the RSF opened 200 clubhouses with TV screens and other services for people to enjoy the World Cup for free. It was supported by local governments, youth groups close to the RSF and the Sudanese Football Union.

Yet in places like Burri, a neighbourhood that has been a centre of the revolutionary pro-democracy movement, resistance committee activist groups have urged a boycott, Mohamed Ahmed from Burri Football Club told MEE.

The RSF offered to give Burri Football Club televisions to screen the games ahead of the World Cup kickoff in November.

"We rejected to receive these screens because the population of Burri rejected it. We have martyrs, our sons from Burri been killed, so we couldn't accept this offer at all," Ahmed said.

Sports analyst Hassan Faroug told MEE that many saw Hemeti's campaign as a governmental intervention in footballing activities - something that could attract sanctions from Fifa, football's international governing body.

"We see Hemeti trying to target the youth and turn them to his side through these cheap things. But that won't work and I believe that this may lead to sanctions from Fifa because it violates the independence of football in Sudan," he warned.

Football was just the latest venture the RSF has been splashing out on. The paramilitary has also opened schools and clinics in remote areas, backed initiatives to deliver clean water, delivered medics and medical supplies to communities hit with dengue fever and HIV, secured Covid-19 vaccines from the UAE and elsewhere, and sponsored tribal reconciliation talks.

And while those causes have brought relief to the needy, journalists and tribal leaders told MEE that they had been offered large amounts of money to promote the RSF and its flagship causes. They said they refused the offers.

International recognition

One way Hemeti's RSF has sought international recognition is by helping combat migration to Europe. It set up a large base, known as Chervrolit, in the desert between Sudan and Libya to crack down on those seeking to travel to Europe for economic or political refuge.

Hemeti has repeatedly urged the EU to recognise his efforts in blocking migration routes to Europe. And though the Khartoum Process between European countries and African countries provides Sudan with funds for capacity building to tackle informal migration, it is notable that the EU has been forced to deny that those funds have ended up in RSF hands.

Hemeti's attempt to find favour abroad began in 2019, when the Canadian firm Dickens & Madsen, owned by Israeli ex-spy Ari Ben-Menache, was paid $6m to lobby on behalf of the paramilitary leader.

Three sources close to Hemeti told MEE that he is also being given support from senior Emirati intelligence officers, and has recruited several top Sudanese political advisers.

Meanwhile, Russia-based Facebook accounts pushing content targeting Hemeti's civilian political rivals have also been identified and shut down.

Facebook's parent company Meta did not disclose which Russian networks were behind the accounts, but organisations linked to the Wagner Group private military contractor, which has ties to the RSF, have previously been accused of similar tactics.

As reported owner of the al-Junaid gold-mining company, which operates in River Nile, Darfur, South Kordofan and other states, Hemeti likely has cash to burn.

Wagner-linked Russian mining companies, which are close to the Kremlin and supportive of the Sudanese military establishment, are also known to pay Sudan's military large sums for access to the country's gold reserves.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.