'I'm coming to kill you': Life as a hostage of Sudan's Rapid Support Forces

It was Eid al-Fitr, around 3pm, when he heard someone say: “The assassination team has arrived.”

Yaslam Altayeb, a 49-year-old Sudanese businessman with Dutch and British citizenship, was being held by Sudan's paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in a Khartoum military base.

Alongside him was someone he knew only as "the doctor", a reserved man who had told him he had a PhD in finance and worked for a prominent bank, but nothing else. Whenever Altayeb tried to speak to him, he told him to shut up.

Hearing the sound of the door being unlocked, Altayeb steeled himself for the worst. "It's done," he recalls thinking.

Four men came inside. "They were really scary people. They were wearing turbans, and they carried AK47s. There were pistols on their hips, and two knives."

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

One of them turned to the doctor. "Hatem, come. Your time has arrived."

It was the last time Altayeb was to see his cellmate.

As Hatem was led away, the man turned to Altayeb and said: "Look over there, there is a Quran. Start reading. When we're finished with this guy, we will come for you."

But they never did. Instead, Altayeb overheard heated words in the courtyard outside his room.

"They said to Hatem: 'You should have talked yesterday, you should have given us the information.' There was a little bit of silence and then the sound of shooting. And then they brought another person. Again, I hear arguing, and again I hear shooting."

Altayeb kept perfectly still. He'd been accused of being a spy. If they saw him moving, trying to see what was happening, they could use it as proof.

Once the sound of the muezzin rang out, he took his chance to see what had happened.

Moving to the bathroom to wash for prayer, he saw someone lying under a sheet, dead. Close by was a pool of dark red blood.

'Take him out'

Just over two months later, Yaslam Altayeb is now in London, far from his captors.

But the memories of the 15 days he spent in RSF captivity tumble out, propelled by anxious energy and a desire to reveal the horrors he and his country have been subjected to.

The war in Sudan erupted in the early hours of 15 April. Tensions had been building for weeks between the regular military, led by General Abdel-Fattah al-Burhan, and the RSF, a powerful paramilitary force led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, better known as Hemeti.

No one knows for sure who fired the first bullet, but RSF fighters had flooded into Khartoum and appeared to have a clear plan to strike the army headquarters, where Burhan was staying.

Khartoum has since become a battleground, as the RSF and Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) fight street to street. To the west, in Darfur, the fighting has reignited ethnic conflict. And to the south, rebel groups have joined the fray, complicating the situation even further.

Hundreds of people have been killed since mid-April, and 2.5 million Sudanese displaced.

It is far removed from the Sudan of 2019, when longtime autocrat Omar al-Bashir was removed from power by a popular revolution - a hopeful era when Altayeb was doing business in his country again after many years away.

Altayeb was woken that Saturday morning not by gunfire and blasts outside, but by a phone call from his brother, asking him what was going on.

"My house has excellent insulation, I didn't hear a thing," Altayeb tells Middle East Eye. "I opened my curtains, and saw smoke rising from the army headquarters."

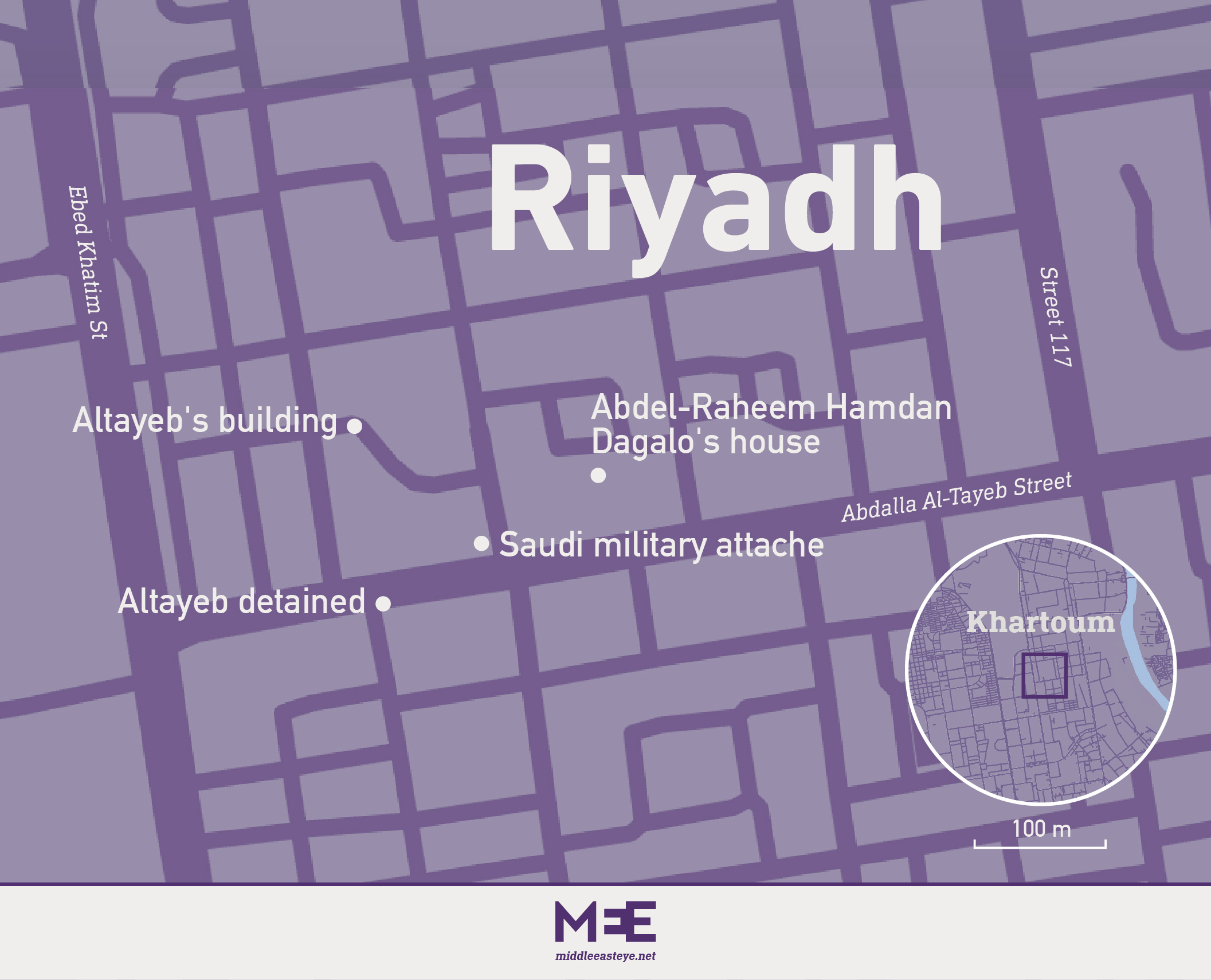

A successful businessman, with companies in everything from construction to wholesale meat, Altayeb’s home was located in Riyadh, a desirable and upmarket district in the capital’s east.

Within view was the office of the Saudi military attache. Just beyond, a residence belonging to Abdel-Raheem Hamdan Dagalo, Hemeti's brother.

Riyadh is known for its peaceful streets, where youth gather to watch flash cars drive past. It has some of the best restaurants in town. "It's the kind of place people take their girlfriends on a date," says Altayeb.

Outside the military attache office is a tree, beneath which a woman sells strong coffee every day. Here, neighbours gathered to chat. Altayeb even got to know members of Abdel-Raheem's staff, including his office manager.

But looking down from his fourth-floor terrace that Saturday morning, all Altayeb could see were RSF fighters, pick-ups with anti-aircraft guns mounted on the back, trucks full of ammunition, and military hardware.

Above, SAF MiG fighter jets swooped low over the buildings, the jet blast from their engines driving him back inside.

Altayeb shared the building, which doubled up as an office, with three Chinese business partners and a cleaner. They decided to stay put.

"The gunfire was 24/7. Anti-aircraft guns were booming as they tried to shoot down drones. They were like bomb shells, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom."

At one point, his building was strafed as fighters shot at a passing MiG, cutting the water supplies. What little food they had ran out quickly. The RSF, too, seemed to have little to eat: Altayeb could see fighters knocking on neighbours' doors, asking for supplies.

Altayeb is diabetic. After two days, he'd run out of food. By the 19th, he began feeling seriously unwell.

"I started feeling my fingers and toes getting numb. That's an indication my blood sugar is getting very low. I thought OK, I'm dying anyway with a bullet or by low sugar or hunger, and we don't have water."

Altayeb left the house. Outside, patrolling RSF fighters confronted him with probing, paranoid questions.

A young fighter, who Altayeb says could not have been much older than 15, told him to empty his pockets. Out came a red passport.

To the teen soldier, his Dutch passport was highly suspicious. "Are you a diplomat? Are you a spy?" he asked.

In fact, Altayeb told him, he worked for the RSF. Before the war, his company had been contracted to expand several RSF military bases, including Taiba, south of Khartoum. Though he'd previously had issues with payments, relations were good.

But in the weeks leading up to that Saturday, Altayeb had sensed something was stirring. During a site visit to one of the RSF bases, he had seen a huge build-up in forces.

Soon after being denounced by the young soldier, an officer started going through Altayeb's recent phone messages. One showed he'd been sent rumours that Hemeti had been killed in an air strike.

Another, with the Dutch foreign ministry, included his live location, which he had been asked to send for safety purposes. Recent calls showed he had been in contact with a friend who is a former intelligence officer and a very senior commander in the army.

It was enough.

Altayeb was taken to Abdel-Raheem's house, which appeared to have been transformed into an operations centre. Suddenly he was punched in the back of the head.

"You're not Muslim, you're a traitor, you're disgusting," the officer screamed at him. He snatched Altayeb's prayer beads from his pocket and started beating him with them, before telling a fighter to "take him out".

Did that mean take him away - or kill him?

“That minute,” Altayeb says, “I’m 110 percent confident I’m finished.”

Only the chief can decide

It's not known how many people the Rapid Support Forces have swept up since the war broke out. Kholood Khair, director of the Khartoum-based think-tank Confluence Advisory, told Middle East Eye that entrenching itself in residential neighbourhoods and detaining civilian targets has been a key strategy throughout the conflict.

Pro-democracy activists, journalists, doctors, union leaders and members of Sudan's mercantile class have all been targeted, she said.

"I think the RSF is targeting people who represent key pillars of the Sudanese state that they're trying to destroy in order to make way for a new state that would more readily embrace them," she told MEE.

Middle East Eye has asked the Rapid Support Forces for comment, without reply.

Altayeb was now bruised, hungry and weak. The RSF took him to a base near the airport that houses offices previously used by the intelligence services.

There he met Ali Dakharo, a senior officer known for being a leader in the student wing of former president Omar al-Bashir's National Congress Party.

Dakharo asked him why he was not more supportive of the RSF's battles with the army. "When you have a disagreement with your father, do you hit him with a stick?" Altayeb replied.

"Oh, you are a troublemaker like they said," Dakharo said, "a real submarine," using the word sometimes applied in Sudan to spies.

Dakharo told Altayeb his fate was out of his hands. Only "the chief" could decide. "By this he means Hemeti's office," Altayeb says.

He was then taken to a building in the complex. In the middle, he says, was a courtyard covered by a metal roof. On the western side were two rooms, separated by a bathroom. Another two rooms stood on the eastern side, with a storage room between them. On the south side was a container of petrol, which Altayeb feared would be hit during air strikes against the RSF.

Next door was a hanger, used to keep around 200 civilians, the majority seized from the streets of Riyadh. There was also a barracks where members of the Sudanese military were held.

Satellite imagery of the complex shows buildings identical to the ones Altayeb describes.

Altayeb seemed to be somewhere they brought prominent captives, or at least ones they weren't sure what to do with. When he arrived, Hatem was already in his cell, a repurposed office with a bed and a mattress on the floor.

Over the next two weeks, Altayeb watched a rolling cast of detainees brought into his building. Some were kept with him. Others were shot dead in the covered courtyard, visible from Altayeb's open cell door.

Four of these killings Altayeb saw for himself. Others, like Hatem, he heard happen through the walls.

"Hatem was executed. I don't know why. But the way these people look and the way they behave and the way they speak, you know they mean it. I could see it in his face. He meant it when he said to me, 'I'm coming to kill you.'"

'He walked over to the guy, took his AK47 and emptied it on the dead body'

- Yaslam Altayeb

Once, Altayeb says, two fighters brought a man accused of being a thief. They made him sit facing a wall. Occasionally, the detainee tried to turn his head towards his captor and tell him something. The fourth time he tried it, one of the fighters shot him in the head.

"He just raised his pistol. The thief fell down dead. And then they carried on talking as if nothing had happened. I was not shocked by the killing. I was shocked by the response.

"After they had finished talking, he walked over to the guy, took his AK47 and emptied it on the dead body."

Many of the men brought into Altayeb's building were retired army officers, or people in the military who held rank but performed civilian services, such as medics, engineers or architects.

Altayeb says the RSF would force them to dress in military uniform and take their photographs, later publicising their capture as highly valued members of the armed forces.

At one point, Altayeb got talking to someone who worked as a medic in the Sharq al-Nil hospital, one of Khartoum's biggest. They told him the RSF had closed off the upper floors of the hospital and the capital's best surgeons and doctors were taken there for urgent work on a senior leader.

"Later, one of the officers told me, yes, it was Hemeti," Altayeb says.

Killings, torture and humiliation

Altayeb was held for 15 days. After the execution of Hatem, other men were brought to his room.

One was the son of a prominent banker. Two of them, Khaled Zayed and Omar*, were RSF officers on secondment from the intelligence service. They had been arrested by their own men on suspicion of having dual loyalties, and were first held in the Republican Palace on the south side of the Blue Nile as it came under heavy bombardment.

When Omar and Zayed came to Altayeb's building, they were distraught. "Omar was very upset, very emotional. He told me he felt betrayed. He said: 'I am a commander of a unit, and I wasn't told about what was going on.'"

For two weeks, the four of them witnessed killings, torture and humiliations in the courtyard outside their room.

The paramilitaries struggled to provide food for their captives or themselves. For a few days, they lived solely off the meat of sheep taken from shepherds.

Out of sight was a mass grave. RSF fighters would arrive at the base in bloodied pick-ups carrying people killed in battle. Detainees who had been summarily executed were also dumped there, Altayeb says.

"Someone came carrying a plastic bag dripping with blood. 'Where is the grave?' he said. He was there to bury his colleague, or what was left of him."

Altayeb says he tried to remain calm throughout.

"I was watching. Not processing, not feeling anything. Things were just happening in front of me."

Altayeb recalls one of his cellmates "freaking out".

"I told him there's nothing we can do. If you're meant to die, you die. Just let it go. At the end of the day, it's only dying. Either it will be a story we tell, or we die."

Then, one day, Dakharo called Altayeb into his office.

"He grabbed my hand like we were very close friends. And he said to me: 'Haven't we treated you very well.' I said yeah, by taking my freedom. And he started laughing. He says: 'Yeah, because we are foreigners, you look down on us, we are from Chad, from Niger.'"

The backbone of the RSF's forces are ethnic Arab fighters drawn from Darfur militias, and they often have family links that traverse Sudan's borders. Hemeti's own family is spread between Sudan and Chad.

Altayeb was sat down and given clean water to drink.

"Remember I told you your fate is not in my hands?" Dakharo said. "OK, well now we have word from the commander's office. You're going home. But we are not releasing you. We have to hand you over to your embassy."

He was then handed a phone.

The first person he spoke to was Hemeti's legal adviser. "He said: 'We are sorry, it's a misunderstanding. But the Dutch and British got in touch with us, and we're letting you go.'"

Then Hemeti's media adviser, Fares al-Nour, called. He also apologised.

Then Altayeb spoke to a third person, who greeted him in Dutch. It was the Dutch foreign minister. There was a plane waiting to take Altayeb to the Netherlands.

But the RSF wanted to leave Altayeb on a bridge and make his own way to the plane. He believes if he had been released there, he would have been shot by a sniper, and his death blamed on the army.

Instead, Altayeb was dropped off at the US embassy, then taken to Port Sudan before the British took him to Cyprus and finally Birmingham.

"By the time the plane was landing, I just started crying. Tears were running down my face."

'I want to make change'

For the Sudanese businessman, recounting his experiences is a way to put pressure on the Rapid Support Forces to release his cellmates such as Omar and Zayed. People close to the two officers agree.

According to Altayeb, every time army warplanes target the area, Omar and Zayed are tied up and put next to the fuel store.

"They want them killed, but not by them. By an army air strike, artillery or something."

Khair of Confluence Advisory says: "The RSF are leveraging hostages. One, as human shields, but two, against the Sudan armed forces.

"The RSF recognised that unless they took human shields, which is a war crime, that they would be under much more SAF bombardment," she adds.

"I think in many ways they overestimated the SAF's willingness to protect not just its own troops but also protect the state they helped to create."

Despite his experiences, Altayeb is desperate to go back to Sudan. He has set up a charity, Helping Hands (SAWAEID), to help vulnerable Sudanese.

"I want to go now, to be totally honest with you. I want to make change in Sudan. That's why I returned in the first place. But now it has become urgent for me, to make real change, so these kinds of things never happen again."

*Name has been changed for security reasons

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.