The murders of Syrian truffle hunters are not all they seem

Omar and his friends leave at dawn, when the air is at its freshest. Some see eastern Syria as oil country. These men are looking for another kind of underground prize: desert truffles.

"When I find them, I feel like I'm digging up a treasure from the ground," the truffle hunter told Middle East Eye, speaking from the eastern city of Deir Ezzor.

"It is really hard to describe the flavour of truffle. It is so delicious, and it has so many health benefits."

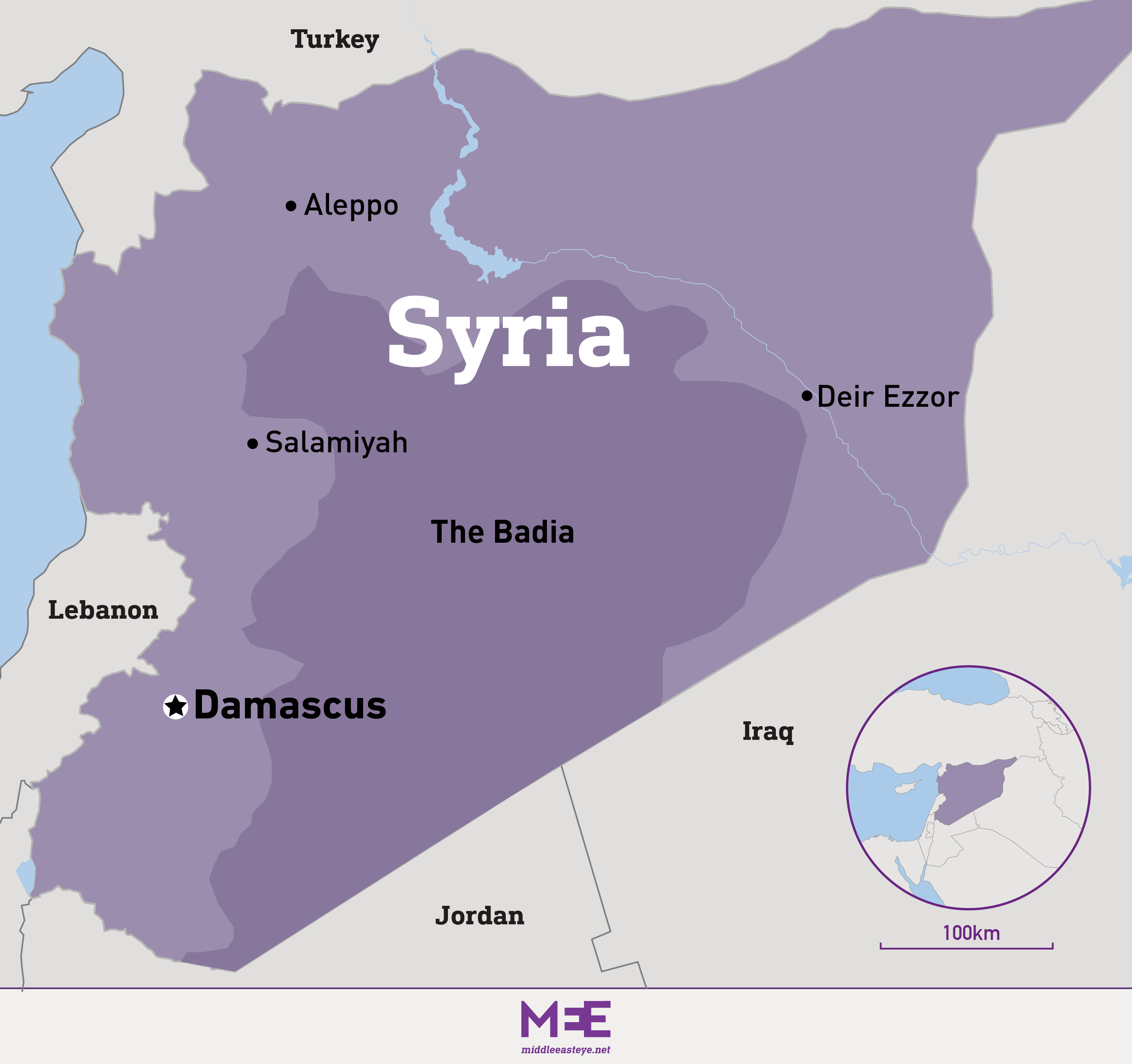

For centuries, hunting for these delicacies has been an enjoyable - and lucrative - pastime. Truffles, known in Arabic as kemmah, can be found in the deserts of Egypt, Iraq and the Arabian Peninsula. But ask anyone around Deir Ezzor, and there's no question the very finest can be found only in the Syrian Badia desert.

In war-torn Syria, however, the truffles have begun to be given a new name: blood fruit.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Over a 70-day period up to mid-April, around 240 truffle hunters were killed in eastern Syria, according to the UK-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights activist group.

"It's really exciting work despite all the deadly risks," said Omar, using a pseudonym due to security concerns.

Officials and media reports have placed the blame for the deaths on landmines and the Islamic State group (IS), which has sleeper cells in the area.

But over two months, truffle hunters, residents and relatives of the victims told MEE that Iranian-backed militias were also to blame, slaughtering people collecting truffles over disputes around extortion and territory.

The largest single attack was in the desert around western Syria's Homs, when 53 members of the Bani Khaled tribe were shot dead in April while searching for truffles.

'It's really exciting work despite all the deadly risks'

- Omar, truffle hunter

Although the state news agency SANA said IS was responsible for the attack, members of the tribe accused Iranian militias of being behind the massacre.

Medical workers are pressured to place the blame on IS as well.

A nurse working in a hospital in Salamiyah on the Badia's western side spoke to MEE shortly after a landmine killed nine truffle hunters by exploding under their vehicle.

"They just brought the bodies," she said, catching a moment to speak after seeing yet more victims arrive.

"There are many deaths per month as a result of local clashes or mines planted by warring parties, but we document them all as a terrorist attack by IS to avoid problems."

Big business

Desert truffles grow between late winter and early spring, fed by the thundery nights of heavy rain.

They tear through the soil like bubbles rising from water, and sharp eyes can spot their gnarled and filthy corners poking out of the surface between February and April.

If not collected they can return to the earth, sinking about 10cm to be hidden once again.

Although truffles are not mentioned in the Quran as a blessed fruit, like figs and olives, Syrians believe they are referred to in a hadith that speaks of a liquid extracted from something resembling a truffle, which is said to be very effective at treating eye diseases.

Hundreds of tonnes are estimated to have been harvested this year. A kilo can be sold for 70,000 Syrian lira (about $8 at the black market rate) to 100,000 lira locally, and in Damascus that rises to 180,000 lira. That's more than a monthly salary for public employees.

In a rare moment of luck, one hunter found a truffle that weighed about 5kg, worth more than $100.

Clearly, in Syria's shattered economy, truffles are big business.

This year, the Syrian government said it granted some 2,800 export licenses worth $72m. The largest share of these were for truffles, the chairman of the Damascus Chamber of Agriculture told the state-backed al-Thawra newspaper, without specifying exactly how much.

"This year's season was excellent as 75 to 100 tonnes were sent to the Damascus market every day. There were daily exports to the Arab Gulf countries," Muhammad al-Akkad, a member of the Vegetable and Fruit Merchants and Exporters Committee, told local media.

Deadly traps

Landmines scattered in former battlefields and front lines have impeded agricultural work, including truffle hunting, and exacerbated Syria's food security crisis, which the World Food Organisation estimates affects around 13 million people.

The town of Salamiyah and its surrounding villages are blighted by the deadly traps.

For years, the area was contested between IS, Syrian rebel groups and pro-government forces. When the Nusra Front rebel group and IS turned on each other in early 2016, forces supporting President Bashar al-Assad began heavily landmining the strategic Athria-Khanaser road, which divided its enemies and gave Damascus access between Aleppo and Hama.

Government troops and allied militias planted thousands of landmines to protect their positions and checkpoints from attacks along this road, a tactic they would repeat in areas they controlled in Hama, Deir Ezzor, Homs, Raqqa and Idlib.

According to the France-based Syrian Network for Human Rights activist group, pro-government forces are responsible for the majority of landmine casualties. Around 3,400 civilians were killed by landmines between 2011 and April 2023, it said.

Though Syrian authorities and media say mines killing truffle hunters this year have been left by IS, on the ground people are more sceptical.

In February, when nine workers were killed when a landmine exploded under their truck in another attack in the Salamiyah area, a resident told MEE: "This time, the mine was placed after the workers passed and exploded upon their return. IS doesn't have that strength now to break through dozens of security checkpoints and place a mine that easily."

"Most of the mines that we routinely see during our work are Russian made," a truffle hunter said.

The danger of militias

As for shooting attacks, suspicion is placed primarily on Iranian-backed militias, forces that have played a key role in propping up the Assad government over 12 years of war.

"The militias linked to Iran have headquarters and military bases throughout the desert," an activist based in opposition-held areas of Hama province told MEE.

According to the activist, most bases fly the Syrian government's flag, with militias trying to disguise themselves as regular troops to avoid attacks by Israel, which regularly strikes Iranian-linked targets.

"They target anyone who approaches the bases," said the activist, who requested anonymity for security purposes. He added that the militias are also known for their attacks on shepherds and their flocks, providing video footage of dead sheep in central Syria.

"Of course, everyone says it's IS because that is the easiest. No one bothers to investigate for long, verify the news, or contradict the official narrative," he said.

"Here, each militia controls a specific area or several villages, and employs labourers to collect truffles or do other work. Anyone working without coordinating with them will be a target," he said.

A job advertisement on a Facebook group linked to Iranian militias, seen by MEE but which has since been deleted, sheds some light on the advantages of working for one of these groups.

Recruits are offered meals, a bed and solar panels to charge their phones, and must work 20 days a month for 280,000 lira. The work mostly entails manual labour, such as construction and agricultural work.

According to residents of areas controlled by the militias, employment with them allows recruits to move freely without harassment and avoid conscription into the Syrian army.

Moayad al-Abdullah, a Berlin-based activist from the region, said the Badia is divided by competing militias of different backing.

"Some join the [Russian-backed] National Defence militia that supports the Syrian businessman Hussam al-Qaterji,” he said.

"While others join other Iranian-backed militias, including the forces of the Fourth Division that support the Syrian businessman Muhammad Hamsho.”

Sometimes, they even come to blows, with weapons and in online media.

"Violent clashes erupted late last year between militias backed by Russia and those backed by Iran, to control checkpoints. Eventually each militia had its own checkpoints and areas of influence," Abdullah told MEE, citing local reports.

Abduction

Navigating these competing militias has become a fact of life for Syrian civilians. Truffle hunters often must pay for access to lands they have scoured for generations.

"Simply, you have to be cooperative and able to pay money to enter and collect truffles in the area of influence of one of these militias if you are not one of their members," said a Deir Ezzor-based truffle hunter, who wished to be identified as Khaled.

"Often, one militia attacks truffle workers who are in the area of influence of another militia, claiming that this area belongs to them or that the workers have not paid."

According to Khaled, militiamen often escort truffle hunters. But this "sometimes leads to clashes with attacking groups, and at other times makes workers and their escorts a target for IS or kidnapping".

Many fighters have been killed as they escorted truffle hunters. Nineteen were killed in a massacre in mid-April, when unknown assailants attacked truffle workers and their escorts near Salamiya. Twenty-two truffle hunters also died in the attack.

Kidnapping is also a significant danger.

The relative of a truffle hunter abducted in the Badia described to MEE how "a peaceful group, not associated with anyone" were attacked while they worked in March.

"They went out in the morning like the rest of the people to collect truffles and provide for their families, but they disappeared and did not come back," the relative said.

"A few days later, the kidnappers called us and asked for $20,000 to release only one of the 12 people kidnapped," he added. "We don't have the money."

Five days later, five of the hostages were found dead.

Almost everyone in the area seems to have a different narrative of the incident. Some residents told MEE the hostages were members of the National Defence militia, others that they were linked to an independent faction known as Asoud al-Sharqia. All seem to agree that Iranian-backed militiamen conducted the operation.

Inevitably, the authorities said the Islamic State group was behind it.

Middle East Eye spoke to another relative of a truffle hunter taken hostage in a separate incident. He said it was clear from their conversations with the kidnappers that these were no IS militants.

"One of the kidnappers spoke to us over the phone during negotiations, telling us in a colloquial tone to pay the ransom," the relative said.

Islamic State members are known for using formal Arabic, not the local dialect, and using the Hijri calendar. Yet this man said "youths" instead of the usual term "brothers" when describing his fellow IS members, and referred to the date as March 2023.

Though the spectre of IS may be used as cover for inter-militia conflict, it is a threat nonetheless. In fact, the group's ability to expand is being boosted by the competition between pro-Assad forces in the desert, western governments fear.

A Middle East-based British official told MEE: "The UK has also long made clear our concern about Iran's reckless and destabilising activity in Syria, which puts at risk the security and prosperity of the whole region."

Fadel Abdul Ghany, chairman and founder of Syrian Network for Human Rights, says truffle hunters and other labourers are the victims of a bloody power struggle.

"Iranian militias are primarily responsible for all the attacks because they have the greatest control over the region, and have a great record of violence and abuses," he told MEE.

"We frequently monitor the attempts of these militias to control the region completely, including commercial and agricultural materials. Their goal is for everyone to work under their authority."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.