'Only the basics': In Syria everyday staples have become luxury expenses

Suha al-Atassi and her family have not bought bread for more than two months. Cooking oil is a luxury and buying petrol risks danger or extortion.

A family of two adult children and their parents, the Atassis live in As-Suwayda, southwestern Syria, one of the worst-hit areas in a country suffering from an economic collapse that has followed a ten-year war.

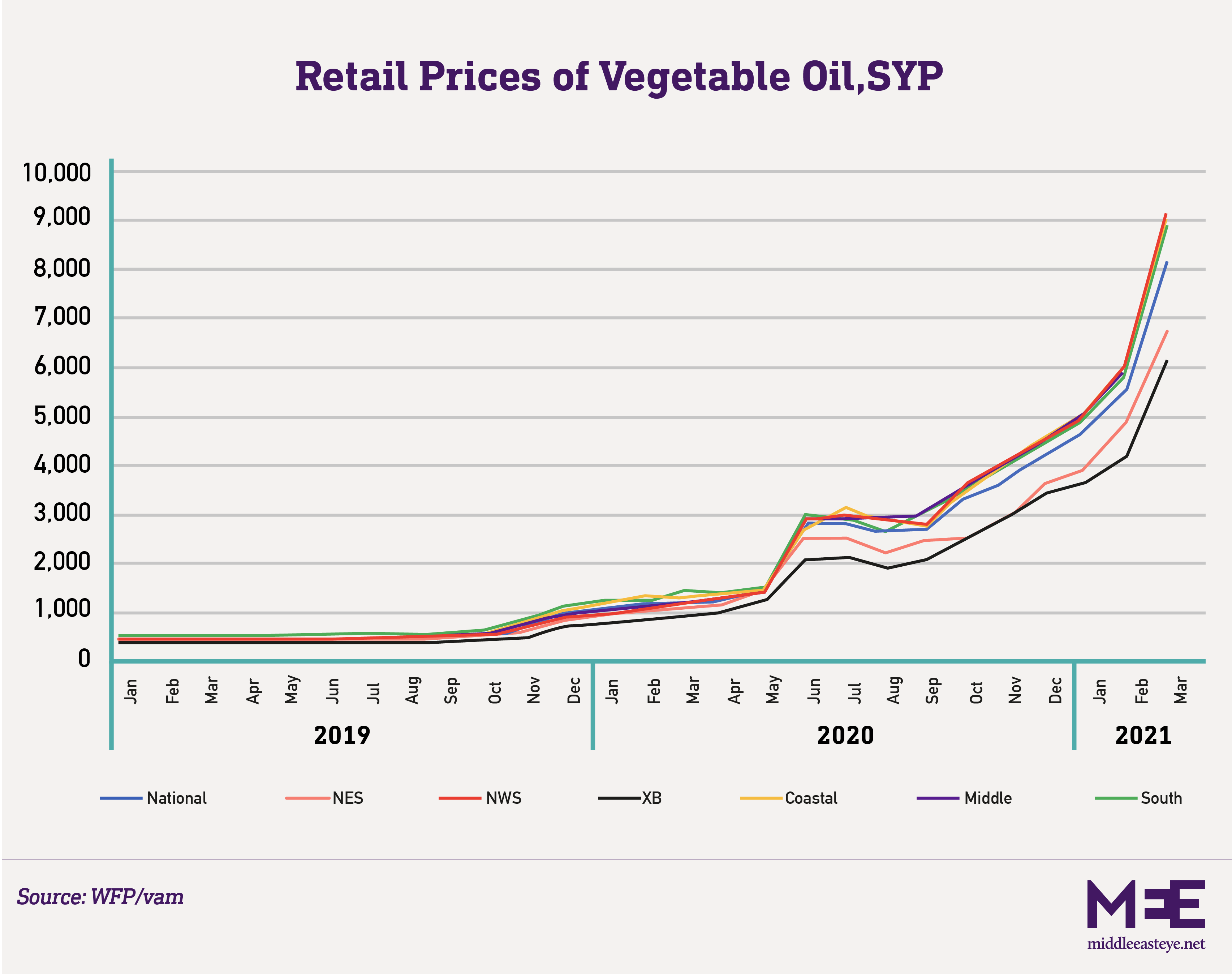

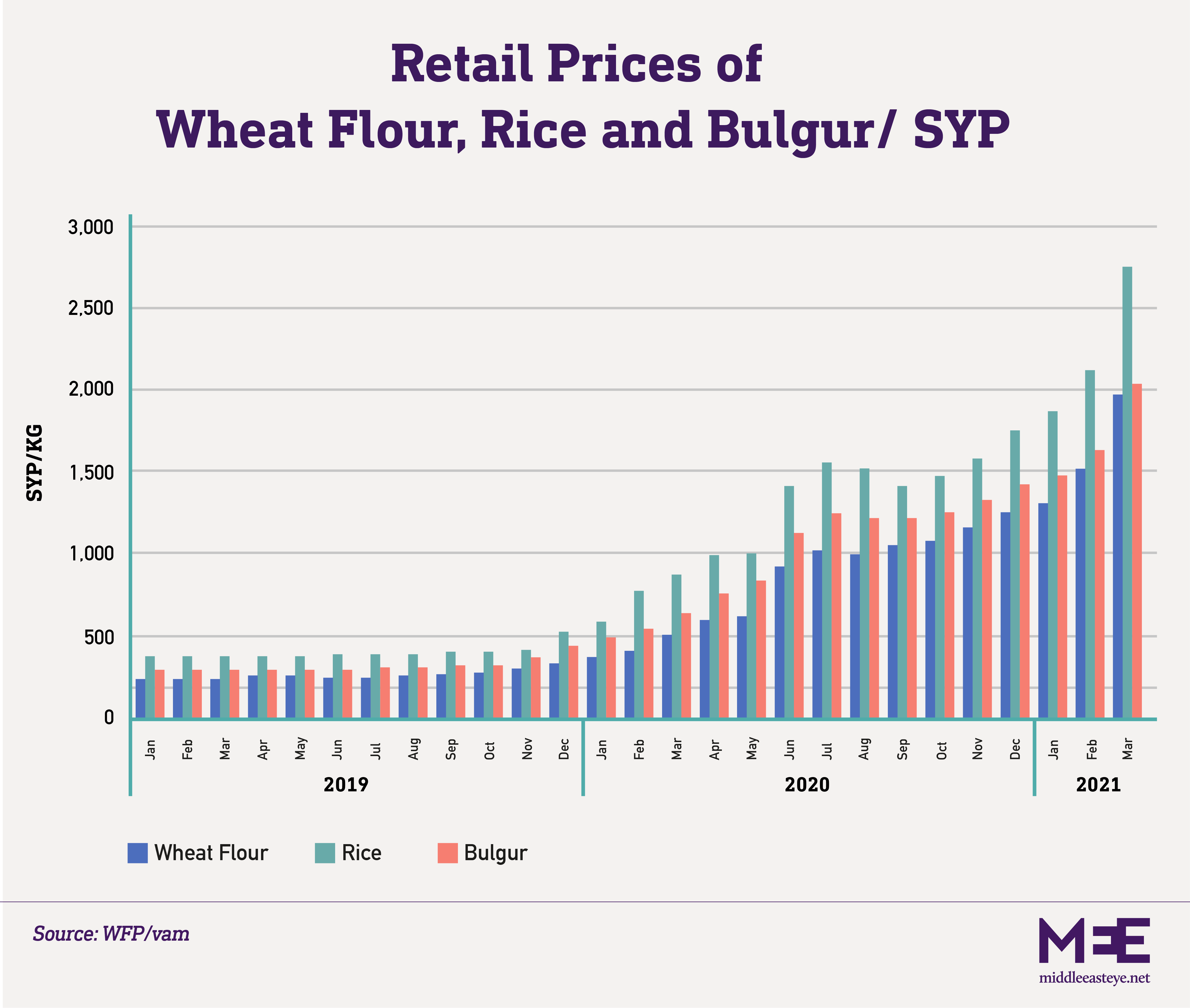

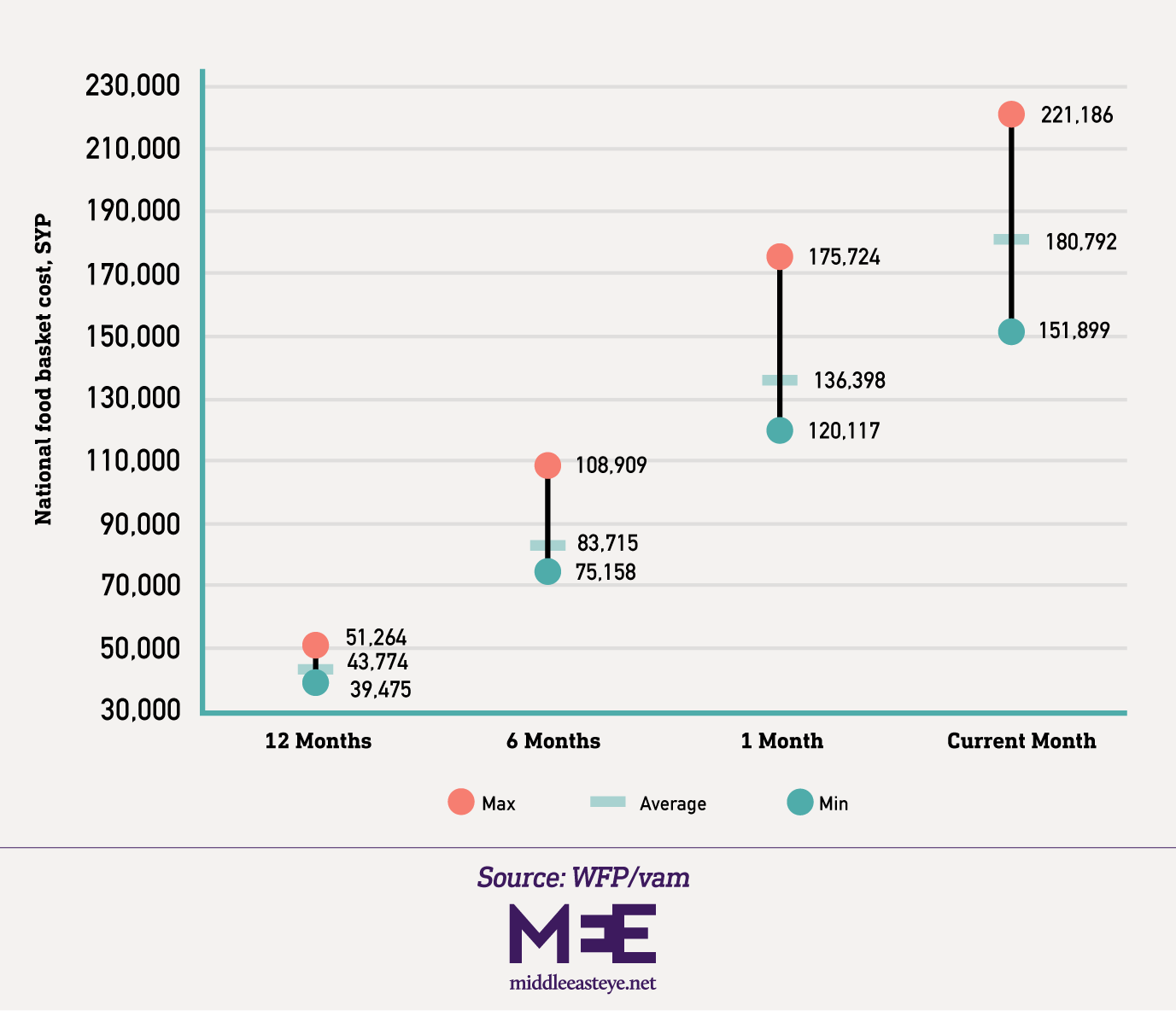

Prices for food in Syria have increased nearly fivefold during the past few years, leading families to make difficult compromises.

Earlier this month, UN officials warned that if the Security Council fails to approve the continued operations of the only border crossing open for aid to enter Syria, the situation will get even worse. Currently, around 1,000 UN trucks enter the Bab al-Hawa crossing from Turkey every month to deliver food, medical supplies and humanitarian aid to those in the northwest.

All of the border crossings from Jordan near the Atassis, however, have been shut down or do not allow the passing of humanitarian shipments, so such aid rarely makes it all the way down to their rural southern village. As-Suwayda also offers fewer creative options to mitigate some of the mounting economic stressors compared to the opportunities available in more urban areas.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

"[Damascus and Aleppo] are large cities with more jobs, people have more income there and there's a lot of markets so traders can't monopolise goods and prices," Suha told Middle East Eye. "Here there are a limited number of traders and small markets, so they can control and raise prices easily since there is no alternative."

'Black market gangs'

Because Suha does not have younger siblings that can waste their days away in bread lines, her family goes without.

Waiting in line to fill up the family car at one of the three gas stations in town is risky and also time-consuming, so instead, when petrol is absolutely necessary, she pays the black market price for 40 litres to be delivered, even though she knows she will only receive half of that.

'Meat of all kinds, frying oil and all fried foods have become a luxury'

- Suha al-Atassi, NGO worker

"Most of those standing at the gas station are smugglers and black-market gangs. I've already tried to stand [in line], but it's a matter of luck. I'd stand in the long line for days, but when the fuel comes, the gangsters will come and get into the line in front of us - there's a lot of problems," Suha said.

Introduced in 2016, Syria's "smart card" programme was set to subsidise fuel to make it more affordable, and was then years later expanded to cover some basic goods. But Suha said the project has been a failed venture that still requires people to stand in unreasonably long queues. "The whole smart card project is a stupid project, it's a stupid card," Suha said.

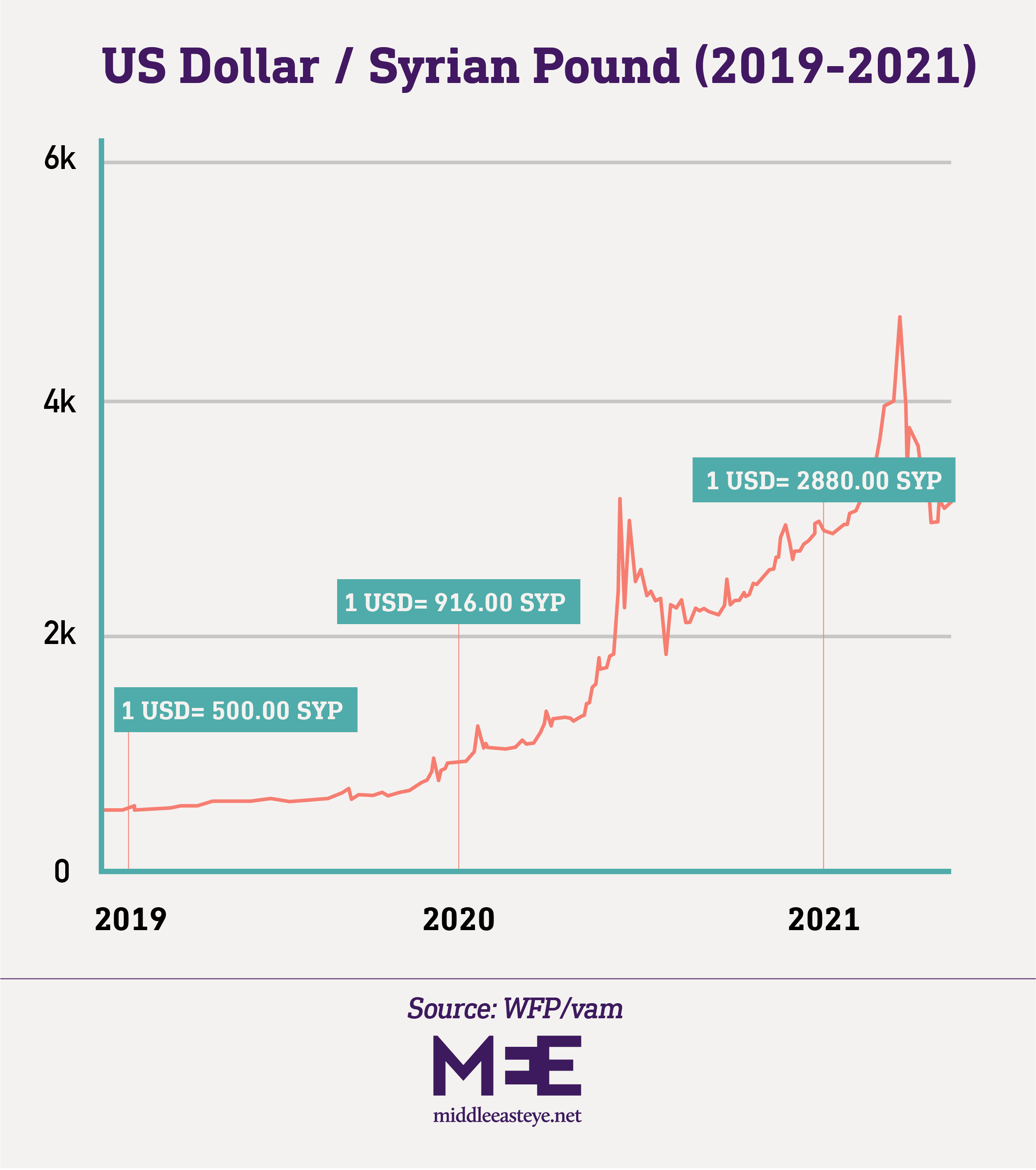

Damascus raised petrol prices in the government-held parts of Syria in March by more than 50 percent after the value of the Syrian pound (SYP) hit record lows on the black market.

In April, the government raised its official exchange rate to 2,512 SYP to the US dollar, doubling the previous 1,250 to the dollar exchange rate. The increase has had a marginally positive effect on Syria's central bank.

The exchange rate on the black market, which is the rate that most affects regular people buying everyday goods, however, still sits at about double that amount.

During the last two weeks of March, the black market value of the pound experienced a sudden nine percent drop, causing many shops to close for a few days to avoid taking on significant price losses while waiting for the black market exchange to stabilise.

As a result of the depreciation, the cost of food - already at an all-time high - increased by 30 percent, according to the UN's World Food Programme (WFP).

The cost of food is too much for the Atassi family to keep up with, so they rely on the bare minimum to survive.

"We try to secure only basic materials such as eggs and cracked wheat. Meat of all kinds, frying oil and all fried foods have become a luxury. For cooking, stores sell oil with a cup, less than a quarter of a litre," she said.

Medication is also expensive and hard to come by. Suha said their poor diet means it's difficult to ward off sickness, which is more worrying than ever, given the Covid-19 pandemic.

"If you feel sick today you can hope to get medications about four days later," she said, adding that her family owes a debt to their local pharmacy that equates to about half her mother's monthly salary.

Suha, whose name has been changed for her family's protection, is luckier than many, she said, as she works for an NGO that pays better than most local jobs. Her father has a monthly pension of less than 50,000 Syrian pounds - officially about $19 but only worth about half of that on the black market. Meanwhile, her mother is a government employee with a slightly less salary.

Her brother, a student of dentistry studying in Aleppo, cannot work while keeping up with his studies, so the family does what they can to support him.

"My brother would like to work in a market or something, but we refused because this affects his studies," she said.

'All the people are angry'

Suha waits up to four hours a day for a bus to take her to work. The workweek has dwindled down to three days a week for many, including her, since transportation is scarce.

"Private buses operate two days a week and allocate another two days to fill fuel. But they are also selling their fuel allowances to black market traders, which for them is more profitable," she said.

"So, I put a stone in the street in a comfortable way that I sit on for hours until the bus comes. People chat with each other for the first half-hour, but then everyone becomes so angry that you can't really hold a conversation - all the people on the street are angry," she said.

'Why would I give birth to a child in this unknown - the people with children here only have God to help them'

- Imad Sarim, former real estate agent

Imad Sarim, a man in his 30s who also lives in Suwayda, told Middle East Eye that he often climbs on to pick up trucks that make rounds through the city, paying twice the bus rate to get to work. Some weeks there is no fuel at all, and the trucks never come.

Imad, whose name has also been changed, was once a real estate agent in Suwayda, but now does odd jobs in construction and agriculture or "anything useful", since the housing market has become untenable.

"The rents are very expensive now and the demand has decreased dramatically. Rent has turned from about 50,000 to 200,000 for furnished homes - about four times higher than last year," Imad said.

A single man, Imad tries not to think about the life and family he could have had before the war and subsequent economic crash.

"Planning to get married is very expensive these days and how would I even feed my future son? Why would I give birth to a child in this unknown - the people with children here only have God to help them."

Outside of work and trying to gather supplies for his family, he tries to stay home as much as he can.

"I try to avoid going out to avoid problems with people, people are all angry about poverty and lack of basic materials," he said.

At times he has turned to alcohol to calm his mind, often sitting down with a bottle of arak when he is home from work, posting pictures of the milky drink on his Instagram stories. His village was once known for the production of the sweet, anise-based liquor.

"I just want to get some rest and avoid my headaches and thinking about continuous power outages - when the days are very cold drinking keeps me warm instead of heating," he said.

'There was a crisis before the sanctions'

Syria's economy has been hit from multiple sides. While any country would struggle after ten years of war, the Syrian government has done little to meet international demands in exchange for aid.

It has also charged people exorbitant fees - one of the administration's biggest sources of income - to military-aged men who fled the country or refused to conscript in the army. In February, the government announced plans to seize property and assets of Syrian refugees and internally displaced people who fail to pay.

"The state has no reasonable politicians and has not yet been able to create a dialogue with the foreign countries to resolve their crises, it is a failed state, and they have been laughing at human beings for ten years," Imad said.

The economic crisis in neighbouring Lebanon, which has limited its ability to export, has also exacerbated the situation in Syria. Russia, one of the Syrian government's main allies, has shown little indication that it is willing to fill in any shortfalls.

Meanwhile, US sanctions targeting the Syrian government and its officials have made banks hesitant to work with humanitarian efforts, over-observing sanction requirements despite aid waivers out of fear of secondary sanctions.

The US's Caesar sanctions, passed in December 2019, seeks to pressure the Syrian government into capitulating to international demands of accountability for its many war crimes.

Named after the Syrian photographer who leaked photos of thousands of people killed by Syria's intelligence service - the Caesar Act has strained the resources of the government, which has not ceased its attacks on civilian areas in rebel-held enclaves.

Still, most of the people who spoke to MEE said it was the Syrian government they blamed for their dire situation, not US sanctions.

'The main reason for the sanctions is the regime, it has lost its legitimacy'

- Rashad al-Bustani, taxi driver

"The regime is the main cause of the crisis. There was a crisis before the sanctions, there were already long queues at the bakeries and gas stations. The Syrian regime is the main reason in everything that happens or will happen," Magdi Nassar, a young man in his 20s who works for a local NGO, told MEE.

Rashad al-Bustani, a taxi driver in Suwayda and the head of his family, agreed.

"The humanitarian situation is the same and the crisis is the same in all provinces because the Syrian regime is the same, the real problem is the regime," Rashad said.

"The main reason for the sanctions is the regime, it has lost its legitimacy, it's an internationally condemned regime that has committed war crimes," he continued.

"The sanctions are on members of the Syrian regime, not on the people and do not include food, but the regime represents as if it is innocent, and that sanctions are the cause. They sell humanitarian aid to the people; all the people know that the survival of the regime is a continuation of the crisis, exacerbating it," he said.

Rashad said that his family, like many others he knows, relies on aid and relatives that live abroad to wire money for survival. Luckily, his landlord has not raised the rent even though the average monthly fee for homes like his has increased drastically.

"I couldn't buy a house before, and even if I had, I would have sold it by now so that my daughter could live better," he said.

"Today's daily income is not enough for food," Rashad continued. "I can't provide food or clothes for my own child," he said, adding that he fears his daughter may have to drop out of school - a common occurrence amongst Syria's youth.

"This makes me live in constant grief, being unable to meet her most basic needs.

"But I drive a taxi and there is no fuel, so how will I work?" he lamented, adding that he is grateful that he only has his wife and one daughter to support.

As to how to remedy their situation, Rashad is at a loss.

"I don't know, I'm a civilian. I don't have a solution, even for my daughter, I don't think she has a future," he said. "The solution for me is to go out of the country."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.