The tale of a Syrian gun smuggler

We had just taken a hellish route out of Syria. For at least an hour we had climbed up and down through mountains and woods, holding on to the branches of trees and suffering in the scorching heat.

After the barbed wire of the border in the middle of this mountainous region, we walked down for a further half an hour before we finally arrived at the main road, from where the smuggler took us to his home on the Turkish border.

After a bus journey in Turkey from Islahiye to Gaziantep we sat down that evening, eye-to-eye with refugees for whom the hellish escape route through the mountains is routine.

Despite the relatively basic surroundings, Idris, his wife Fatima, their children Rohan and Sivan, and Idris’s brother Hasan and his wife Ceylan, allow us to stay with them and share their tales that are a microcosm of the Syrian civil war.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Life in Syria

Before the uprising began four years ago, brothers Hasan and Idris worked side by side in their Aleppo restaurant.

While Idris’s wife Fatima owned a hairdressing salon, Ceylan had almost no education. Aged only 17, she dropped out of school at 12 when her father took her out because he could not see the benefits of an education if even the best students could not find a job and when dropouts could go and quickly make money. Every time Ceylan sees Hasan scrolling through Facebook, she is jealous because she cannot read.

Idris's daughter Sivan has gone down the same road. When the war started, she was just about to begin school. But then the schools were bombed. Idris watched from a hilltop as the bombs fell on the Sheikh Massoud district of Aleppo. Then they sold their restaurant and went back to their village, Kurdan.

In Kurdan they stayed at their parents’ home, with 12 people in one room. There were no schools. Sivan was almost eight and had never gone to school. For a year they lived without water, electricity or work. The money they earned by selling their restaurant ran out. But then something happened that made their situation life threatening: Fatima gave birth to a daughter, Rohan.

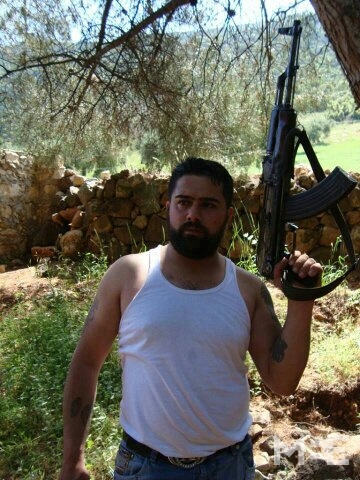

Idris needed to find a job because the baby needed warm milk and diapers. Hasan had an idea: maybe people needed guns? That day, almost exactly a year after weapons destroyed their source of income, weapons became their new source of cash.

Small cogs in somebody else’s war

“At the beginning we bought bullets and Kalashnikovs from soldiers who were fighting for the regime and sold them to rebels, who used them against the army led by the regime,” said Idris while he cut vegetables in his apartment in Gaziantep.

“Kalashnikovs cost around 2,000 euros [just over $2,000], the soldiers sold them for half that price. They themselves were searching for a source of income to provide for their families because they got paid very little. After a while I bought weapons from every militia and sold them to every militia, even to the new Kurdish militia YPG.”

Idris and Hasan thus became small cogs in the machine of war.

“Our boss told us what we had to deliver and where. I took the orders and left without asking any questions. I just needed the money,” said Idris. “We got around 100 euros ($100) for a delivery from Afrin to Aleppo [about 60 kilometres away]. I did not get rich doing that, but it was enough to keep my family alive. The bosses make hundreds of thousands of euros; we were just workers.”

Getting past the various militia checkpoints with suitcases filled with weapons proved difficult but Hasan and Idris decided to take drastic measures. Failure to deliver meant no payment, which they could ill afford.

“I took my wife and my children with me because families are less suspicious,” said Idris. “At one checkpoint they shouted that our house was bombarded and that we were fleeing. It was nerve-wracking because the soldiers could gun me down in front of my children.”

Sometimes it went wrong.

“At a checkpoint guarded by Jabhat al-Nusra they took my passport and saw that I am a Kurd; they beat me for hours.”

“It was terrifying,’ said Fatima. “I hate weapons, and [our daughter] Sivan saw everything, hundreds of guns.”

Eventually it all got too much. After a year, the going got too tough and the money was just not enough to keep justifying the risks.

“Everyone started to sell weapons,” said Idris. “I saw all the leaders of the major militias going to one man in the north of Aleppo.”

“Small sellers were put out of business. We crossed the border illegally, over the mountain, searching for a job.”

An unattainable dream

While the families had always said that leaving was a last resort, they now fled north to Turkey. The two brothers went first and got work at a pizza restaurant.

In their first days in Gaziantep, the pair slept on the restaurant floor. After a few weeks they rented a tiny apartment in the same building, and brought their families over.

The influx of some one million Syrian refugees has meant big business for developers. Everywhere you look new buildings are rising from the ground, but the conditions are cramped and poorly made.

“When we had just arrived we did not even have chairs or beds. Now Rohan and Sivan sleep on a mattress,” said Fatima.

Rohan is a cheerful young girl. Sivan is much shier. She often isolates herself and puts make-up on in front of the mirror.

Fatima too is not who she used to be. Once a proud lady of the house who mingled with lots of people at her hair salon, she is isolated and fulfils her household chores impassively.

“When I was pregnant, it was even harder,” she said.

Both Fatima and Ceylan recall the humiliations at the state hospital before the birth of her baby. “They made me wait at the entrance for two hours,” said Fatima. “The nurses are like machines, without feelings. I felt completely alone ... Giving birth without your family is very saddening.”

The story across the border in Turkey is not all that much different. Ceylan is pregnant, she faints often. Will it lead to complications? Ceylan does not know.

“Yesterday I went to the children’s hospital, but they did not let us in. In the next hospital we had to wait for half an hour, and when we finally spoke to a doctor he told us to go to the city hall first, to apply for an identity card for refugees,” Ceylan said.

Ceylan has a card issued by AFAD, the Turkish relief agency that provides shelter for Syrian refugees. The card should allow them access to state hospitals.

“But even with this card, they still refuse to provide care,” said Ceylan. “Turkish patients who arrive after us are treated before they treat me. I want to give birth in a private clinic, but that will cost us 500 euros ($510.)”

That is the family income for a month, even with Hasan working 84 hours a week at the restaurant.

“A Turkish labourer would earn twice as much,” said Hasan. “Today I made 500 euro-worth ($510) of pizzas. I am the machine and the boss makes the money.”

“We have already asked for a raise, but he just laughed at us. We work here illegally, without a contract. From seven until seven, 12 hours a day, seven days a week, no holidays.”

“Family members of ministers of the Syrian opposition government eat here every day,” he continued. “They earned wealth through corrupt means, wealth they were able to earn because of the revolution that depleted us.”

Tirade with a smile

It sounds like a tirade, but Hasan is smiling. He says he needs to smile to stop himself from turning into a machine. “F**k the revolution, f**k freedom,” he said. “I hate those words if those words mean that those people have money to burn while we do not even have the money to provide for our healthcare.

“Those words cost us our country, our homes, our jobs and our education. We, the refugees, pay for their war with our demolished lives.”

It is a full circle: yesterday the brothers were providing the weapons for which they are paying the price today.

The hatred burns inside Hasan. Whether Hasan and Idris sell weapons or pizzas, they can’t help but feel that they are only helping other men get rich.

The families also worry that their children will not be able to escape the cycle.

“She [Sivan] is 10-years-old and has not been to school for a day in her life," said Fatima. “We do not have the money for the admission fee. If she will ever go to school, she will be a teenager amongst toddlers.”

But there are also some good moments in Turkey. When Fatima takes Sivan to the pool, Sivan becomes a child again.

“We are going to the swimming pool,” we yell the next morning. Rohan stands at the door, jumping for joy. On the way to the swimming pool, she glances at the high buildings, the cars, and the people, all those new sights in the world outside of their apartment. At the swimming pool, she cannot be stopped. "I am very happy today," she says. The swimming pool is so near, and yet so far away.

Her father, Idris, shows a similar childish wonder when he watches videos of babies and animals online. He also keeps a little duck in his apartment in the big city to sustain a bond with nature, which makes it hard to think that he was once an arms smuggler and that the need to provide for his children also helped him destroy the lives of other children.

Bave Selah is one of the most famous Kurdish musicians, and a family friend.

As he sits in Idris's apartment he explains that: “The blood of our children on the bullets is like the product that makes gold shine: it makes money.”

“All the old songs are about life in the countryside, about the bond between humans and nature,’ he said. “Children and animals are still close to the soul of the earth, as it existed before the human race did. Hate has not yet had an impact on them.”

“But millions of Syrian children have seen more hate during one second than most people do in all their lives,” he added.

The last supper

During our last meal together, we dared to ask a question: is there a way out, a future for the children? Day and night, Hasan and Idris walk around with this question in their heads.

They explain that the apartment and the job are just temporary solutions until they can move on to something better, but this temporary solution has already dragged on for more than a year.

Fatima has a brother who lives in Germany and a sister who lives in Denmark. “They tell us about the schools over there, and while Skyping with them, I saw what the houses look like. If anybody would tell me ‘You can leave now’ I would go with them even in my pyjamas,” she said.

“Maybe Idris will go to Europe on his own, and bring us over later. But in order to do so, he needs to save enough money.”

Hasan could go to work in Dubai again, but only without his family. For him this is not an option while Ceylan is pregnant.

And so the daily grind goes on with the families drifting between machine-like states and moments of hope, like millions of other Syrian refugees waiting for a resolution that has yet to come.

- Additional reporting by Roni Hossein and Annemiek Poelman

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.