'There is no opposition': How Egypt's 'real politics' fizzled and faded

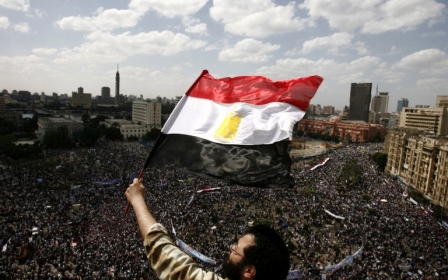

They were 18 days that seemed to have launched a golden era for opposition parties in Egypt, a time that some have even called "the birth of real politics".

Within a year of the 2011 uprising that brought Egyptians of all religions, social classes, political and ideological affiliations together in Tahrir Square and brought about the end of Hosni Mubarak's decades-long rule, more than 90 new political parties had been established and elected to parliament.

Five years on, with those same groups not only on the political sidelines but also deeply divided among themselves, that era has proved to be short-lived.

“In today’s Egypt there is no real opposition," Shadi Hamid, a senior fellow of the Brookings Institution, told Middle East Eye. "None of the groups that are part of the current political process such as those in parliament can be called opposition."

Nagwan al-Ashwal, an Egyptian political analyst at the Florence-based European University Institute said: “Today, the different groups, especially those with differing ideologies, refuse to speak to each other.

“There is a lot of bitterness and an inability to move forward from what each group perceives as the unforgivable mistakes of the other.

“The revolutionary movements, such as 6 April, keep blaming the Muslim Brotherhood for leaving them in Mohamed Mahmoud [Street near Tahrir Square] and siding with the military, while the Brotherhood does the same in regard to Rabaa,” Ashwal added, referring to the August 2013 massacre by security forces of supporters of the Brotherhood-backed elected president Mohamed Morsi, who had been removed from power in a military coup weeks earlier.

'Real politics'

For many, Hamid said, the period after Mubarak's fall really did seem to mark a new beginning of "real politics" in the country.

Previously, there had been a distinction between political parties co-opted by the state and opposition groups working outside the political system, but in March 2011 a law was introduced allowing new parties to form for the first time since 1977.

Opposition groups seized the opportunity, and a new stable of political parties - from young Islamists to secular, liberal and nationalist groups - launched themselves into the political landscape.

“Egypt’s opposition groups were together, taking part in one process and working to create a change,” said Ashwal.

“They coordinated actions and carried out an effective action plan as formal organisations, as well as working as individual members in the various groups,” she said.

Yet, almost as soon as momentum had started to gather, the seeds of what Hamid calls "lingering distrust" between the group were sown.

In the early hours of 19 November 2011, Egypt's riot police violently attempted to disperse a sit-in of protesters whose friends and family had been killed and injured at Tahrir earlier in the year and wanted their killers tried in court.

After six days of clashes, 51 people had been killed in an action now simply referred to as Mohamed Mahmoud, named after the street where the fighting began.

Many revolutionary groups blamed the Muslim Brotherhood for not standing their ground against the military during the clashes.

Another divisive moment for Egypt's opposition was 14 August 2013, known as the Rabaa massacre, when Egyptian security forces forcefully cleared a sit-in of mostly Muslim Brotherhood supporters, killing at least 1,000 people.

This time, the Muslim Brotherhood blamed secular and liberal opposition groups for abandoning them at Rabaa square as security forces violently removed the protesters.

The faultlines in Egypt's opposition are broadest between the Muslim Brotherhood and smaller liberal and secular groups, Ashwal said.

Such difficulties in seeing eye to eye have further broken ties between secular and liberal groups on the one hand and the Brotherhood on the other.

Although such animosity does not exist among secular and liberal groups, analysts say there is little room for change without the Brotherhood.

"The Brotherhood remains the biggest opposition force. The smaller opposition groups can talk to each other all they want, but if the Brotherhood is not part of this process, it is dead in the water,” said Hamid.

Fearmongering tactics

According to Hamid there are several other elements beyond mistrust that make it difficult for groups to unite with the Brotherhood.

“It is dangerous for political actors to work closely with the Muslim Brotherhood because they will get punished by the security apparatus," he said.

“The last thing the regime wants is for the Brotherhood and the liberal and leftist groups to work closely together in Egypt.

"They [the Egyptian authorities] have raised the costs, and now everyone is afraid to work with the Muslim Brotherhood, but it is the only way forward,” added Hamid.

This sense of fear has also affected the potential for opposition among the wider Egyptian population.

“There are various factors that pose a major challenge for the opposition," said Sharif Nashashibi, a Middle East affairs analyst, commentator and MEE contributor. "There are harsh penalties for expressing dissent and protests are banned.

“At the same time, there is a sense of public exhaustion and fear, [and many] now feel insecure because of Islamic State and the increasing lawlessness in Sinai … even if people are unhappy, they will not protest,” Nashashibi said.

As the fifth anniversary of the 25 January revolution passes, experts do not expect the opposition to have any successes anytime soon.

“It is unlikely that large groups of people will take to the streets or that a dialogue about democratic change among opposition groups in Egypt will take place,” Ashwal said.

“Until they reach the level of maturity to self-critique and move beyond each other’s mistakes, things will remain the same.”

For some, the division among Egypt's political and ideological groups was inevitable.

"People were united against Mubarak, so they were able for a brief moment to put aside their ideological differences," said Hamid.

"Mubarak was a unique force, but after his fall there was no [longer] a rallying point and the divisions grew."

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.