Threat of Muslim Brotherhood ban leaves community in fear

US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson told lawmakers last month that Washington should prioritise defeating Islamic State militants to then focus on "radical" groups, including al-Qaeda and the Muslim Brotherhood.

The subtle reference lumping al-Qaeda, the militant organisation behind the 9/11 attacks, with a popular political movement that reaches across the Middle East and North Africa, is telling of a broader animosity toward the Muslim Brotherhood in the Trump administration, observers say.

Tillerson’s comment at his confirmation hearing coincided with the reintroduction of a bill by Texas Senator Ted Cruz to designate the Brotherhood as a terrorist group. The legislation did not make it far in the Senate, but it was followed by reports that President Trump is considering designating the organisation a terrorist group via an executive order.

'The Muslim Brotherhood, amongst anti-Muslim bigots in the alt-right, has been merely code language for Muslims in general'

-Dawud Walid, CAIR

While such a designation may harm Washington’s already rocky relations with Muslims across the world, rights groups warn that it may have disastrous domestic effects - that it would enable the government to further scapegoat and crack down on Muslim American groups and individuals.

Right-wing ideologues who were empowered by Trump’s election victory have long accused Muslim activists and public figures of ties to the Muslim Brotherhood.

Veteran Republicans, including Frank Gaffney, a former assistant secretary of defence who advised Cruz during his presidential campaign, have argued that mainstream US Muslim organisations are a front for the Brotherhood to achieve its alleged plan of taking over Western civilisation.

Katharine Gorka, who was appointed by Trump in November to the Department of Homeland Security's transition team, leads a think tank that focuses on the Brotherhood and raises flags about the organisation's ostensible influence in Washington.

'Muslim ban 2.0'

Dawud Walid, the executive director of the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) in Michigan, said efforts to blacklist the Brotherhood are “not driven by foreign concerns, but by domestic demonisation”.

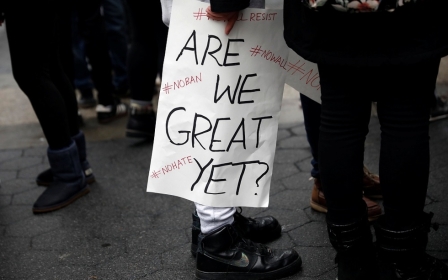

“It could be deployed as a de facto Muslim ban 2.0,” Walid told Middle East Eye, referring to Trump’s executive order restricting entry for nationals of seven Muslim-majority countries.

He added that the designation could turn into a McCarthyite witch hunt to smear Muslims in the US. In the 1950s, US Republican Senator Joe McCarthy led a draconian campaign accusing opponents, scholars, and government officials of communist membership and ties to the Soviet Union during the early days of the Cold War.

“The Muslim Brotherhood, amongst anti-Muslim bigots in the alt-right, has been merely code language for Muslims in general and as a means of demonising Muslim organisations and activists who are promoting Islamic education as well as civic engagement,” Walid said.

He cited the campaign to slander Huma Abedin, the Hillary Clinton aide who was falsely portrayed by right-wing websites as a Muslim Brotherhood operative.

Amid a political deadlock over the US government budget in 2012, then-Congresswoman Michele Bachmann claimed that the Brotherhood has infiltrated the Obama White House, even accusing Keith Ellison, her Muslim colleague in the US House of Representatives, of links to the Islamist organisation. Bachmann advised Trump on foreign policy during the 2016 election campaign.

Threats to funds, residency

Walid warned that the crackdown is not only political. Blacklisting the Muslim Brotherhood would allow the US Treasury Department to freeze assets of American Muslims who are seen as dissenters to Trump’s policies, he said.

The designation of a group as a "foreign terrorist organisation" has debilitating legal effects. Funds related to the group would be immediately frozen, and it opens the door to possible criminal prosecution of people who belong to the organisation. Non-citizens affiliated with the group might face deportation even if they were legal residents, and potential immigrants belonging to the organisation would be denied entry to the US.

Both the president and the secretary of state can designate a group as terrorist if it meets a certain criteria: the organisation must be foreign, engage in terrorism and pose a threat to US national security.

The Muslim Brotherhood, founded in 1928, is an active political organisation with offshoots participating in elections in Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon, Gaza, Tunisia and Morocco. While the movement has engaged in violence in certain places throughout its history, it has largely operated through political parties to achieve its Islamist aims.

The Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi became Egypt’s first democratically elected president in 2012, but he was overthrown by a military coup a year later. Morsi's overthrow was followed by a massive campaign of repression against the movement, in which most of its leaders in Egypt were jailed. Subsequently, Cairo banned the Muslim Brotherhood and declared it a terrorist organisation.

Several Gulf countries that backed the Egypt coup also blacklisted the Brotherhood. However, in 2014, the United Arab Emirates went a step further by designating US groups, CAIR and Muslim American Society (MAS), as terrorist organisations as well.

At the time, the US State Department said it did not consider these organisations to be terrorist groups. Both CAIR and MAS have denied ties to foreign political entities.

Radwan Ziadeh, a senior analyst at the Arab Center, a Washington DC thinktank, said the Brotherhood is a broad movement with numerous affiliated political organisations in many countries where the US is involved.

Negative impact on Syria

Ziadeh, a vocal Syrian dissident in the US, said designating the Muslim Brotherhood as terrorist would further complicate the Syrian conflict, because it is a part of mainstream Syrian opposition bodies, including the Syrian National Coalition and the Syrian National Council.

"It would be difficult for the State Department to have contact with each of those groups," he told MEE.

Ziadeh said the Brotherhood has been presenting itself as a moderate movement in the post-Arab Spring Middle East. Excluding it from the political discussion, he said, would push its parties toward more extreme positions, while making militant groups appear more appealing to people.

CIA analysts seem to agree with Ziadeh's rationale. A summary of an intelligence report obtained by Politico cautioned that blacklisting the Brotherhood would fuel groups like al-Qaeda and the Islamic State group.

Ziadeh said there is a concern that Trump's policies, including the possibility of blacklisting the Brotherhood, are driven by his advisers' anti-Muslim views.

Designating the Brotherhood as a terrorist group would add to the list of controversial decisions by Trump, who has faced nationwide public dissent and protests around the globe in the first few weeks of his presidency.

Shareef Akeel, a US civil rights lawyer, said it is hard to predict the impact of blacklisting the Brotherhood without knowing the details of such a designation.

“Whatever the issue comes down to, I can’t speculate what’s going to happen, but if there’s a law out there that’s going to target one religion, you’re going to see uproar from activists, from attorneys, because that’s not what our nation is all about,” he said.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.