Torture, threats and trumped-up charges: The story of an Egyptian on death row

The first time Nusela Harun saw her son after his arrest, he had cigarette burns all down his neck in geometric patterns.

“It was as if they enjoyed drawing on his neck," she told Middle East Eye.

The nerves in his hands were damaged because of how he was hanged from his wrists during interrogations

- Nusela Harun, mother of Ahmed el-Shal

“His collarbone was fractured, and the nerves in his hands were damaged because of how he was hanged from his wrists during interrogations.”

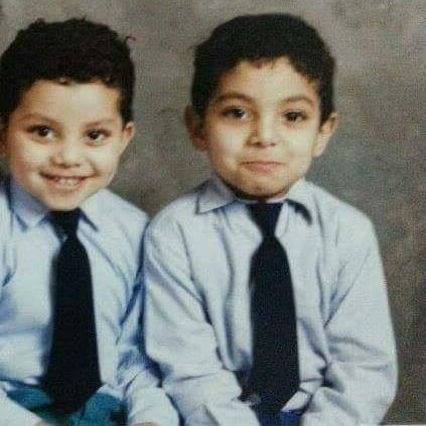

Harun, a lawyer, has already lost one son. Her eldest, Khaled el-Shal, was killed by Egyptian security forces along with nearly 1,000 others during the Rabaa massacre in 2013.

Now she’s worried she’s about to lose another son, Ahmed el-Shal, who has been condemned to death on the back of an apparently false confession extracted from the 30-year-old through torture.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

He would join the 15 young men executed in Egypt since the beginning of 2019, convicted in trials the United Nations has poured doubts on and in a process described by one rights group as a “human rights crisis”.

Alongside Shal, nearly 50 others face imminent execution.

Ahmed disappears

Shal and Harun’s ordeal began on 28 February 2014, when they visited Khaled’s grave in the Nile Delta city of Mansoura where the family lives.

Tending Khaled’s grave had become a weekly ritual ever since he was shot dead in Cairo’s Rabaa al-Adaweya Square, as security forces cracked down on supporters of toppled president Mohamed Morsi following a 2013 military coup.

News from friends and neighbours on returning home, however, would upend that routine completely.

Abdullah Metwalli, the bodyguard of a judge who controversially tried Morsi in a trial condemned by Human Rights Watch as “badly flawed”, had been shot dead earlier that morning.

According to reports, Metwalli had been riding down the Mansoura motorway, when a gunman apparently pulled up beside him and shot him in the head.

Three days after the murder, the state security prosecution issued arrest warrants to 18 people accusing them of forming a “militant cell” to kill Metwalli.

A week later, on 6 March, Shal disappeared on his way to the nearby university where he was studying.

Shal never hid his opposition to the military coup or Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, the general who led it before becoming president. He and his friends took part in regular, peaceful sit-ins to protest Morsi's ousting.

“But he never resorted to violence, even after his brother was killed in Rabaa,” Harun told MEE.

Shal, now 30, had just finished medical school and was doing an extra year of practice.

“He dreamed of being a paediatrician. He was planning to travel to the US to continue his studies,” Harun said.

Hours after Shal’s arrest, security forces raided Harun’s home without a warrant. They searched the house and “turned everything upside down”, she said.

“They attempted to extract confessions from me that Ahmed was intending to kill police officers in retaliation for the killing of his brother in Rabaa,” Shal’s mother recalled.

It seemed like déjà vu. Following Khaled’s killing, authorities had arrested and tortured another of her sons, Osama.

Osama managed to flee Egypt, fearing for his life. This time, Shal wouldn’t be so lucky.

Televised 'confession'

From that moment on, Shal’s judicial process has been irregular and highly problematic. It has also been violent.

Almost exactly a year after he was arrested, a sober-looking Shal appeared on television beside two co-defendants.

As a microphone was passed between them, the youths confessed to Metwalli’s murder. Shal, with dark rings around his eyes, said he shot at the judge’s bodyguard six times from the back of a motorbike.

Interspersed with the confessions is footage of a table covered with arms the three allegedly possessed. Assault rifles, handguns, knives, a shotgun and piles of ammunition.

It was the first time Harun had seen her son since he was arrested.

"I was about to lose my mind," she said about watching the footage. "I felt I didn't recognise him as my son. When we met later after the video, he told me, 'I had to do this for your sake' because they threatened they would rape me if he didn't confess."

Ten days passed until she got word of him again, when a lawyer told Shal’s family that he was being held in the notorious maximum security Scorpion Prison on the outskirts of Cairo.

They threatened to rape me in front of him. This is when he agreed to recite their confession on tape

- Nusela Harun, Ahmed el-Shal's mother

Eventually, three months later, Shal and 23 others were referred by the prosecution to the criminal court on charges of joining the banned Muslim Brotherhood group that Morsi was a prominent member of.

Some of the defendants were accused of “premeditated murder” and others faced charges of being accomplices.

After a three-year trial, in June 2017, Egypt’s highest appeals court upheld the death penalty for six defendants: Shal, Basem Mohsen Elkhorieby (also known as Bassem Mohsen), Khaled Askar, Mahmoud Mamhouh Wahba, Ibrahim Yahia Azab and Abd Elrahman Attia. All but one were students.

Shal is the main defendant in what became known as the Mansoura Guard Murder case, accused of shooting Metwalli. The other five were convicted of being his accomplices.

Slapped, stripped and strung up

According to Harun, however, the conviction was primarily based on false confessions drawn out of Shal through “deadly torture”.

After being “electrocuted and raped with a stick”, Shal still refused to tell his torturers what they wanted to hear, Harun said.

It was then that they threatened to rape Harun in front of him, she said. "This is when he agreed to recite their confession on tape.”

After recording the confession, Shal was transferred to the national security agency headquarters blindfolded. An officer threatened to torture him again if he ever retracted his confession, his mother said.

Harun said she read her son’s torture testimony six months after it was taken.

When Harun received a copy, the lawyer immediately filed a complaint with the attorney-general, but no investigation was ever conducted.

Shal told his mother that he attended a hearing with the attorney-general on 21 March, without a lawyer, and told him that he was innocent and forced to confess. This was also ignored, she said.

Middle East Eye has obtained an official copy of Shal’s testimony during an interrogation, noted down by his legal representatives.

In it, Shal describes in detail abuse meted out by security forces.

Ahmed el-Shal's torture testimony

+ Show - Hide“I deny all the charges, because I was not fully conscious when I said what I said before. When I was arrested, I was taken to the Mansoura police headquarters, blindfolded, slapped on my face, electrocuted, and hung on a door from my underarms.”

“When I was arrested they blindfolded me, and someone started kicking me, but I don’t know who he was because I was blindfolded.

"Then someone electrocuted me on my face, then I was taken to the room of an officer, who stripped me of my trousers and hung me from my hands and feet on a stick; then someone started inserting a stick into my anus repeatedly, and he turned it, and another one started electrocuting me on my legs and neck.

"Then they removed the blindfolds and I saw an officer whose name is Sherif Abu el-Naga. This was the same officer who asked me to take off my trousers then asked me to put them on. Afterwards they hung me on the door from my underarms. When they took me down, I felt that my hands were paralysed.

“I don’t know who raped me with a stick, because my head was on the other side.

“I have bruises on my shoulder and neck, and burns because they burnt it with cigarette butts.”

He says he was slapped, stripped, strung up and electrocuted. According to Shal’s testimony, Egyptian authorities also raped him using a stick.

“Someone started inserting a stick into my anus repeatedly, and he turned it, and another one started electrocuting me on my legs and neck,” Shal recounts in his testimony.

All the defendants in Shal’s case have recanted their confessions.

'Arbitrary deprivation of life'

The confession that Shal says is false and was forced out of him has not only condemned him, but gravely affected his due process as a defendant.

It has been used by the prosecution to justify questioning Shal without the presence of legal representation.

Meanwhile, the airing of the defendants’ confessions on national television ahead of their trial has been condemned by the Geneva-based rights group Committee for Justice, which said it violated the principle of the "presumption of innocence".

It said the prosecutors were aware that torture took place in national security agency offices, but “failed to uphold impartiality” towards the defendants as it “overlooked the torture testimonies”.

There is no accountability where trials are characterised by a myriad of irregularities, including torture

- Agnes Callamard, UN special rapporteur

In addition to confessions, the prosecution primarily relied on the testimony of an Egyptian intelligence officer, Ahmed Khedr Abulmaati, who cited “secret sources” as the source of his information.

Meanwhile, much evidence used in the trial was marred by “major inconsistencies”, according to a letter to the Egyptian government from independent UN experts.

The bullets collected from Metwalli’s body did not match the rifle that was said to have been confiscated from Shal and supposedly used to kill the bodyguard.

Moreover, the motorbike said to have been used in the murder was a different colour to the one described by state security officers at the time.

And a crime scene report indicated that the killer must have been standing near the victim at the time of the crime, rather than riding a motorbike.

Agnes Callamard, UN special rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, and one of the UN experts tasked with investigating the case, told MEE that the Egyptian government insisted in responses to her letters that the sentences were imposed in the context of Egypt’s war against terrorism.

She condemned the death sentences imposed in the case, criticising the international community for its “deafening silence” towards the growing number of executions in the country.

“Those responsible for attacks and killings must be held accountable for their crimes. But there is no accountability where trials are characterised by a myriad of irregularities, including torture,” she said.

“Death sentences in such cases amount to arbitrary deprivation of life.”

'Barely surviving'

Shal is not well. Harun said her son had two brain surgeries to remove tumours, affecting his balance.

“Though he dreamed of riding horses, he was never able to,” Harun said.

“He couldn’t ride motorbikes for that reason either,” she added pointedly.

Shal’s lawyers said during the trial that his condition would prevent him from firing accurately at any target, let alone a moving one from the back of a motorbike.

“It’s impossible,” Harun added.

Now Shal is being held in Wadi Natroun prison, in a tiny cell only just long enough for him to stretch out to sleep, Harun says. He is allowed to leave his cell for one hour a day.

“They have no toilet. They use bags and buckets to relieve themselves,” Harun said.

Things are tough at home too, as Harun and her family are caught in limbo, fearing the worst.

“Life is very difficult after the death of Khaled and the arrest of Ahmed. We are barely surviving.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.