Trump bypassed Congress on Saudi weapons sale. Here's how he did it

Schoolchildren in the United States are taught from a young age that a separation of powers is the backbone of their country's democracy.

The system also comes with checks and balances meant to limit the power that the executive, judicial and legislative branches of government can wield, to prevent overreach.

Last week, however, President Donald Trump threw that civics lesson out the window, declaring an emergency to bypass US lawmakers and green-light an $8bn weapons deal with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo cited recent tensions with Iran to justify pushing the sales through without congressional oversight.

Critics have rejected that justification, noting mounting scepticism towards the Trump administration's claims of an imminent Iranian threat in the Middle East.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

"It seemed more like a manufactured justification that so far is not sitting well with many members of Congress," said Christina Arabia, director at the Washington-based Security Assistance Monitor, which tracks US arms sales and military assistance to foreign countries.

Indeed, senior lawmakers have vowed to push back against the decision.

But the US president holds broad authority, and while the law grants Congress oversight over weapon sales, the administration ultimately has the upper hand.

Here's how it works:

The process

Whether a foreign country is purchasing arms from private American manufacturers or directly from the US government, the State Department has to certify that the sale is in the national security interest of the United States.

The administration then has to notify Congress of details of the deal.

While it does not need lawmakers' approval for the sale to go through, members of Congress have 30 days to try to stop it.

Still, blocking a weapons transfer to a foreign nation is a complicated process. Congress would have to pass a disapproval bill in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, and the president can still veto the legislation.

Because of the historical consensus in Washington over strategic foreign policy issues, Congress has seldom protested administration-approved sales.

It seemed more like a manufactured justification that so far is not sitting well with many members of Congress

- Christina Arabia, Security Assistance Monitor

In fact, US lawmakers have succeeded in passing a piece of disapproval legislation against a weapons transfer only once, and that victory was short-lived.

In 1986, Congress blocked the sale of advanced missiles to Saudi Arabia. Then-president Ronald Reagan successfully vetoed the legislation, but he dropped parts of the purchase to satisfy some lawmakers and avoid a congressional override of his objection.

Congress can overturn presidential vetoes with a two-thirds majority in the House and the Senate.

Despite the difficulty of blocking weapon sales outright, lawmakers do have the power to hold up and derail transfers.

That's what Bob Menendez, the top Democrat on the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, did with the precision-guided munitions to Saudi Arabia and the UAE, which prompted the recent emergency declaration.

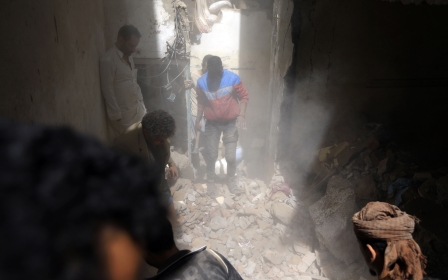

Last year, Menendez halted the entire process by refusing to acknowledge the Trump administration's notification of a sale until he received specific clarifications about US policy in Yemen, where Saudi Arabia is leading a devastating military campaign.

Sometimes, the objection of senior lawmakers convinces the administration to stop the sale on its own, in order to avoid a potential stand-off with Congress that could prove politically costly.

For example, in 2017, then-secretary of state Rex Tillerson stopped the sale of handguns to guards for Turkey's Recep Tayyip Erdogan after protests from key legislators.

Emergency

But the same Arms Export Control Act that gives Congress oversight over major sales also grants the president a way to go around lawmakers.

To bypass Congress, the president must declare that "an emergency exists which requires such sale in the national security interests of the United States".

In practice, the president only needs to submit a justification for such a decision, making the executive branch the sole decider over what constitutes an emergency, Arabia told Middle East Eye.

Despite the relative ease of declaring an emergency, presidents have used that loophole only four times over the past 40 years to push weapon deals through without congressional scrutiny.

Coincidentally, three of those incidents involved Saudi Arabia and its allies:

- In 1979, Jimmy Carter issued an emergency proclamation to ensure the speedy delivery of arms shipments to the Saudi-backed government in Yemen amid military confrontations with the now-dissolved socialist republic of South Yemen.

- In 1984, Ronald Reagan used the same provision to send 400 portable anti-aircraft Stinger missiles to Saudi Arabia during the Iran-Iraq war.

- In 1990, George H W Bush bypassed Congress to send weapons to Saudi Arabia after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait.

- In 2006, George W Bush rushed the delivery of precision-guided missiles to Israel during its war against Lebanon without giving Congress a 30-day notice period.

Pompeo cited those precedents in his statement last week, noting that the emergency determination will be a "one-time event".

"This specific measure does not alter our long-standing arms transfer review process with Congress," the secretary of state said.

"I look forward to continuing to work with Congress to develop prudent measures to advance and protect US national security interests in the region."

Arabia noted that the previous emergency declarations were done during war time, whereas Trump's decision aimed to strip Congress of its powers because of legislators' concerns about Riyadh's human rights violations.

"That's what makes this extremely problematic - because of who the recipients are, because of their abuse, because it's going around Congress for those things," she told MEE.

Since the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi at the hands of Saudi government agents at the country's consulate in Istanbul late last year, Trump has repeatedly defied Congress in support of his allies in Riyadh.

While a Republican-controlled Senate unanimously passed a resolution backing the CIA's conclusion that Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman was responsible for the journalist's killing, the Trump administration didn't budge.

In fact, it has ignored a deadline mandated by the Global Magnitsky Act, a US human rights law, to determine the perpetrators of the crime.

Trump also vetoed legislation that aimed to end US support for the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen.

Marcus Montgomery, a fellow at the Arab Center Washington DC, who tracks congressional affairs, called last week's emergency declaration a "clear escalation" by the White House against Congress.

Even key Trump allies, including Senator Lindsey Graham, have expressed opposition to the administration's decision, he said.

"They're basically accusing the president of stripping Congress of what little oversight that they already have," Montgomery told MEE.

"Even if nothing happens immediately and these arms sales do go through, I could see where in the future Republicans and Democrats could come together to put major, major conditions on future aid to Saudi Arabia."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.