Tunisians turn to online smuggling networks for land route to Europe

Clenching a fistful of dirt, Mabrouk Gaceur struggled to contain his emotions as his eldest son was being laid to rest.

Like thousands of Tunisians before him, 16-year-old Aboubakr attempted to migrate to Europe earlier this year in the hope of starting a new and better life.

But on 5 September, while trying to enter Hungary from neighbouring Serbia, the vehicle he was in crashed into the Danube during a high-speed police chase, killing him and another Tunisian national.

Aboubakr was aware of all the risks, but all he could think about was leaving Tunisia, his father told Middle East Eye shortly after the funeral.

"He kept telling me that all his friends had left, and that his cousins had taken the same path. He wanted out," he added, his voice cracking with emotion.

Like millions of Tunisians, the Gaceurs were hit hard by the country's financial crisis with northward migration seen as the only exit strategy.

The economy, which was moribund for years after the 2011 Arab Spring uprising, experienced further tumult last July when President Kais Saied dismissed the government and suspended parliament in what many observers have called a bloodless coup.

Increases in global food and energy prices sparked by the war in Ukraine have further added to the burden of ordinary Tunisians, pushing inflation to record highs.

The precarious financial climate has seen more than 13,000 Tunisians attempt to cross into Europe since the start of the year, with many seeking dangerous smuggling routes by sea.

According to the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights (FTDES), at least 500 people have gone missing or perished off the Tunisian coast over the same period.

"There are multiple factors that can explain the surge in irregular departures from Tunisia, but usually decisions are influenced by a combination and interplay of social and economic factors," Tasnim Abderrahim, a non-resident scholar at the Middle East Institute, told MEE.

"If we look at figures from the latest Arab Barometer, which was released in July, around 55 percent of Tunisians report that they run out of food before they have money to buy more, which raises concerns about food insufficiency.

"The dual dynamic of rising prices and limited livelihood options has created an expanding pool of migrants, and a lot of people are thinking about looking for other opportunities elsewhere."

The Kazawi army

Stories of crushed dreams and tragedy are common in interior regions of Tunisia such as Tataouine, but they're also accompanied by the success stories of those who reached Europe and made it their home.

At Aboubakr's funeral, several residents told MEE that news of a Moroccan smuggler, who was advertising his smuggling network on WhatsApp and Facebook, had gripped the community.

The smuggler, who goes by the name "Kazawi", charges would-be migrants at least $3,500 for relatively safe passage to Europe, the residents said.

Employing what is known as his "Kazawi army", the journey begins over social media and involves travel across the so-called Balkan route.

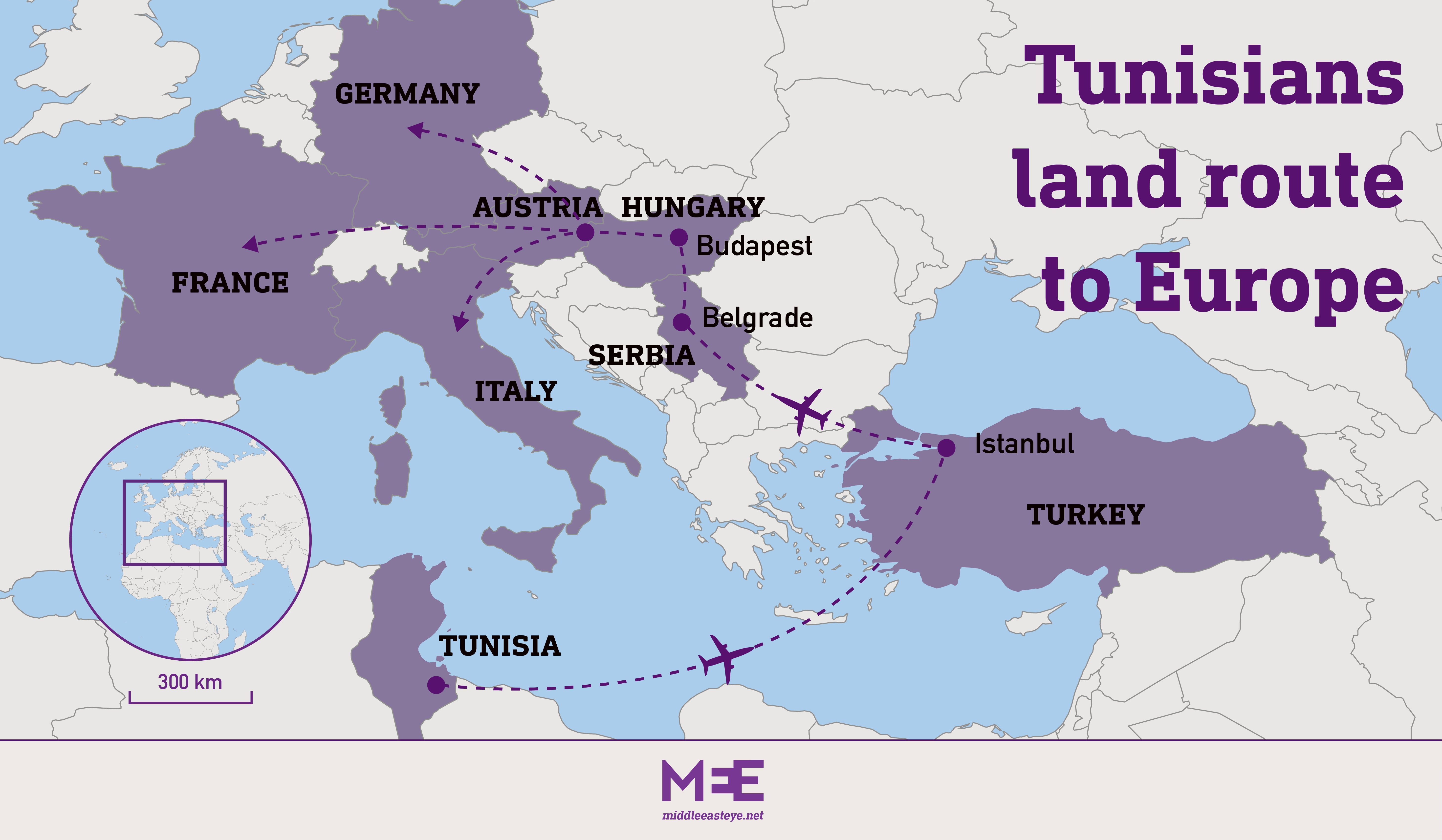

The route involves flights from Tunis to the Turkish city of Istanbul. After a short layover, the would-be migrant takes another flight to Belgrade before travelling across Serbia's northern borders into Hungary or another state within the Schengen zone.

Depending on the type of service, the migrants pay either $3,500 in person or wire $3,800 to an account in France, the sources said.

The migrants are given meagre provisions by the smugglers and head for the Radanovac forest on the Serbian-Hungary border. Their names are then added to a list where they await their turn to cross.

At this point, the amount that is paid will determine the level of comfort for the remainder of the trip.

According to the sources, there are two ways of deciding on how to proceed next. The first is "Tasslima", where the smuggler guides the migrants 30km by foot through the forest, the Danube river and across military lines.

After bustling them into a van, drivers from the Kazawi army will transport them across Hungary and drop them off near the Austrian border. Once there, or at Traiskirchen, a small town south of Vienna, they turn themselves in to Austrian authorities where they apply for asylum.

The second method, known as "Taktiaa", is far cheaper - ranging in cost from $1,500 to $2,000 - but can be fraught with problems, the sources said.

An organising tool

Several would-be migrants told MEE that the Kazawi army's presence on social media remained an important organising tool, and a practical aid for those travelling to and then through the European Union's 26 Schengen area states.

Still, dangers remain.

According to photos viewed by MEE, dog bites, barbed wire scratches and bruises from beatings could be seen on the legs and feet of migrants in the forests near Subotica on the border with Hungary.

MEE reached out to the Hungarian foreign ministry for comment over the alleged use of force, but did not receive a response by the time of publication.

One migrant pointed MEE to videos and messages posted on Instagram. The videos are usually tagged as harka or haraga, a colloquial word used in Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco and Libya to describe Mediterranean crossings.

These videos often include migrants traversing the Mediterranean on small boats and dinghies, but they can also include people packed in vans driving through dusty roads.

In February, a viral haraga video by a Tunisian woman drew worldwide media coverage for apparently glamorising illegal migration.

Meta, which owns Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp, told MEE that videos referencing smuggling services would be subject to moderation and taken down.

A few days after the Kazawi army's page was brought to Facebook's attention, a Meta spokesperson said that it had taken appropriate action and the page had been removed.

"People smuggling across international borders is illegal and coordinating this activity on our platforms is not allowed. We take action as soon as we become aware of it, and continue to work with law enforcement and experts from across the world to tackle this issue," the spokesperson said.

Surge in departures

In an effort to curb so-called illegal migration, several EU member states have intensified pressure on Serbia to tighten its visa regime. The Tunisian embassy in Belgrade told MEE that from 20 November Tunisian citizens needed a visa to travel to Serbia.

The Tunisian Ministry of Foreign Affairs didn't answer MEE's questions over the decision but said: "They are aware of the issue and are currently considering the next steps to follow in face of these new procedures."

"Removing the visa requirement may increase the importance of smuggling networks for Tunisians migrating through the Western Balkan route. The journeys will become longer, more expensive, and more dangerous," Abderrahim said.

Tunisia already restricts travel for under-35s, with border police at airports often requiring parental permits for those travelling to Turkey, Morocco, Algeria and Libya.

Matt Herbert, the research manager for the North Africa and Sahel Observatory at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, told MEE that despite recent boat wrecks off the Tunisian coast, the Balkan route had surged in importance over the course of the last year.

"Considerably more expensive than the maritime journey, this itinerary is seen as both safer than the maritime route and in an era of heightened border enforcement by Tunisian authorities is considered to be more secure.

"From January to August, what we've seen is that over 5,000 Tunisian nationals have been intercepted along the Balkan route. This is up from 842 throughout all of last year," he added.

It's unclear whether it is primarily men who are making the journey, but according to the latest national survey, Tunisia is undergoing a severe brain drain - partly as a result of budget cuts to the higher education and research sectors. Around 39,000 Tunisian engineers and 3,300 doctors left the country between 2015 to 2020.

Mohamed Ali Talbi, a researcher on migration, told MEE that many of the Tunisians who had made their way to Europe blamed the government for their predicament.

'Do you understand what it means to watch two people literally fighting to death, until one kills the other, in a remote Serbian forest?'

- Said, Tataouine resident

Once they're off the trucks or vans, many of these young men can be seen and heard shouting "Rakh la" ("No turning back") and slogans such as "the people of Tataouine", Talbi said.

"This is a way of saying that these young men are loyal to the region rather than the country. It’s their way of saying: ‘We have been neglected by the country and we’re on our own,'" he added.

Said, a Tataouine resident who refused to give his last name, said he had recently helped his brother migrate to Europe a little over a month ago. "It's the government's fault that all these young men are leaving," he told MEE. "I sent my brother because I had no choice, there was no hope or future for him here.

"My brother is a tough man and this journey made him cry, it made me cry. It's not a walk in the park or as easy as people think. He’s seen death.

"Do you understand what it means to watch two people literally fighting to death, until one kills the other, in a remote Serbian forest? That scene will haunt you for the rest of your life."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.