Tunisia's Marzouki says charges against him 'ludicrous' and urges opposition to Saied

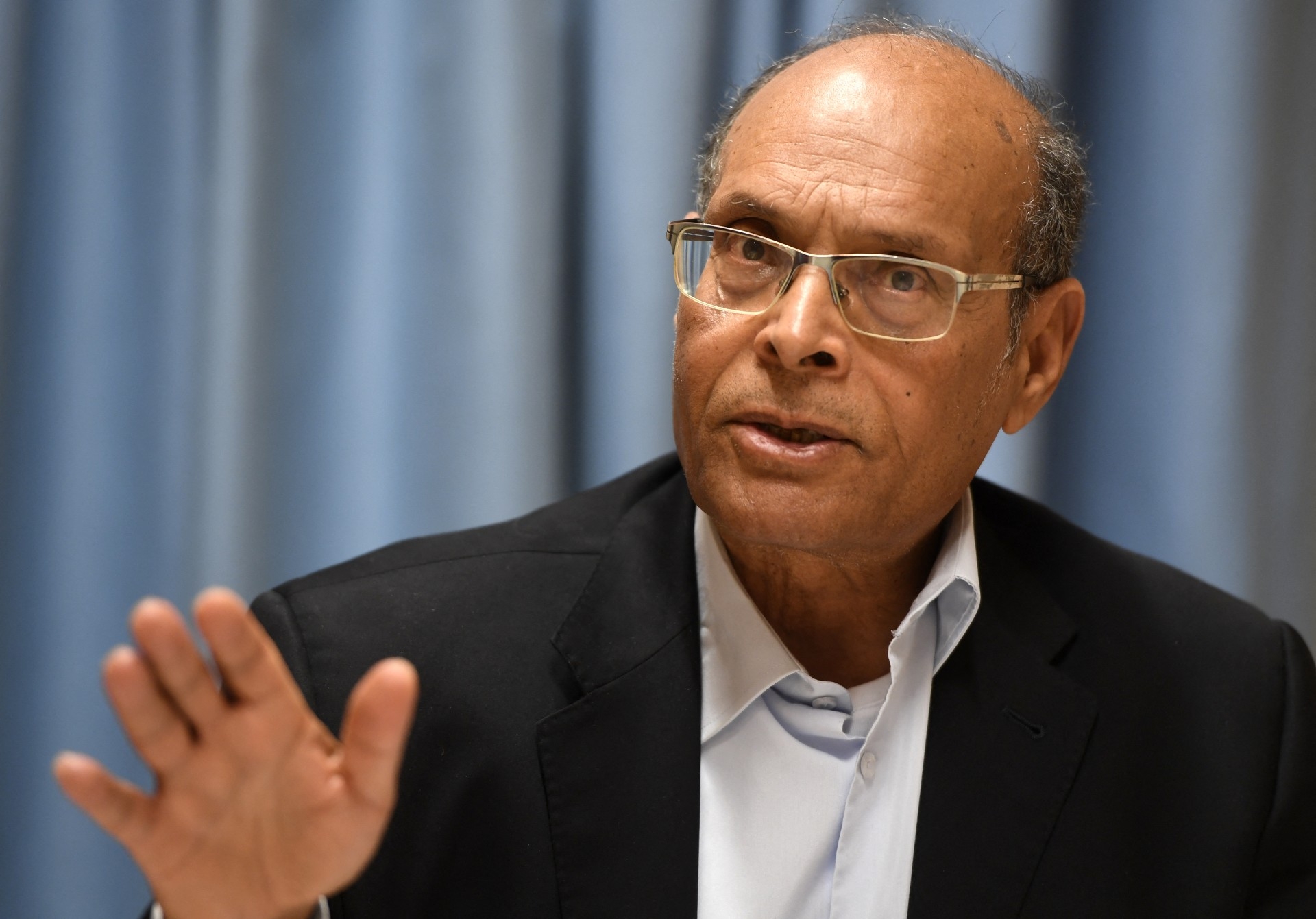

Ever since Kais Saied seized control of all Tunisia’s levers of power in July, the Tunisian president has been on a collision course with his predecessor, Moncef Marzouki.

Marzouki, who served as interim president from 2011-14 as Tunisia emerged from the Arab Spring revolution and Zine el-Abedine Ben Ali autocracy, quickly denounced Saied’s moves as a coup.

In turn, the former president became a target for Tunisia’s judiciary, and on Wednesday a Tunisian court sentenced Marzouki to four years in prison in absentia, on charges of "assaulting the state's external security". Marzouki, the court said, had been connected to agents of a foreign country that aim to "harm the diplomatic situation of Tunisia".

"This lurking dictator will depart, and I will win the cases in which I’m being tried," Marzouki responded.

Speaking to Middle East Eye from France ahead of the judgement, the 76-year-old described the charges as “ludicrous”.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

'The arrest warrant has no value because it was issued not by a court but by a putschist president whom I no longer recognise as the legitimate president of Tunisia'

- Moncef Marzouki

“The arrest warrant has no value because it was issued not by a court but by a putschist president whom I no longer recognise as the legitimate president of Tunisia,” he said.

Like all Arab countries embroiled in the protests, wars, and revolutions of 2011, foreign interference is a charge often levelled at opponents in Tunisia. Marzouki, too, sees foreign hands behind Tunisia’s current turmoil.

“The three main countries responsible for the misfortunes of the peoples of the Arab Spring - i.e. the Syrian, Yemeni, Libyan, Egyptian, and Tunisian peoples - are the United Arab Emirates, the United Arab Emirates, and the United Arab Emirates,” he says.

Many of Saied’s opponents would agree. But it is impossible also to ignore the lack of progress achieved by successive Tunisian governments, whose promises of post-revolution prosperity have fallen flat as economic issues and unemployment worsened.

Power grab

Saied seized power, in a plot leaked to MEE two months earlier, citing skyrocketing unemployment, rampant corruption, and the coronavirus pandemic as reasons to suspend parliament, sack the prime minister and grant himself prosecutorial powers.

Tunisia’s democratic politicians have been accused of concentrating on elections, the constitution, and parliaments, and not on governance, economy and simply making life better for Tunisians.

Marzouki rejects this characterisation. “No, it is not that simple. Yes, we were extremely busy with the political problems. However, under my presidency, we worked on a poverty-reduction programme with the objective of lifting two million Tunisians out of poverty in five years,” he says.

“I sent my advisers to Brazil to study the experience of President Lula. We seized over 300 corrupt businesses. In 2014, I took with me a hundred Tunisian businesspersons on tour in African countries to find opportunities for our industry. I also launched studies on the impact of climate change on Tunisia and in particular the problem of water.”

All these programmes, he says, were stopped in their tracks in 2014 when “the counter-revolution” returned to power.

Dismantling the system

By “counter-revolution”, Marzouki is referring to the Beji Caid Essebsi, who defeated him in the 2014 presidential election.

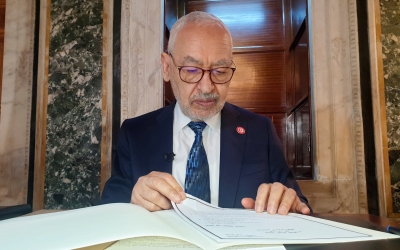

Essebsi was an official under Ben Ali, and his Nidaa Tounes party formed a government with the help of Ennahda, an Islamist party led by Rachid Ghannouchi, who is currently speaker of the suspended parliament.

Though Ghannouchi is loathed by Saied and his supporters, Marzouki says the Ennahda leader was the architect of his own – and Tunisian democracy’s – demise.

“After the coup d'état in Egypt in July 2013, Ghannouchi was afraid of the Muslim Brotherhood's fate. He signed behind my back a contract with Beji Caid Essebsi, the leader of the counter-revolution: the presidency for his protection,” Marzouki says.

“This contract delivered Tunisia to the counter-revolution. It was the alliance of the Ennahdha party with the corrupt parties from the old system that paved the way for Kais Saied.”

Today, Saied is seeking to dismantle much of the political system crafted since 2011. He has promised to draft a new constitution (Saied is a former professor specialising in constitutional law) and create a new, decentralised government with much power given to local councils. Critics have compared his plans to the unwieldy and corrupt Jumhurriyah of Muammar Gaddafi in Libya.

“Decentralisation exists in our constitution but Saied refuses to apply it for the benefit of popular councils, which only existed under the dictatorship of Gaddafi in Libya. Of course, this is not a solution to the defects of parliamentary democracy. It will simply throw the country into a chaos like the one that Libya has known,” Marzouki says.

“Democracy will not gain anything, contrary to what Saied and his supporters claim, because the presidential power will always be the real power.”

Growing disillusionment

Marzouki acknowledges that many Tunisians lost faith in their country’s politics before the July power grab, and support for Saied remains strong among the youth.

“The very bad image of parliament, the health and economic crisis, the ineffectiveness of the Mechichi government have exasperated the population,” he bemoans.

But equally, he says, others were aware of the dangers of such a move by Saeid, and disillusionment is growing.

“Kais Saied's incompetence is obvious. He is now considered as the real problem of the country and no longer the solution. His popularity is declining day by day. Some of his former supporters are now the most virulent against him.”

'Kais Saied's incompetence is obvious. He is now considered as the real problem of the country and no longer the solution. His popularity is declining day by day'

- Moncef Marzouki

Earlier this month, the leader of the Democratic Current party, which supported Saeid’s power grab in July, said the president was “no longer capable of saving the country”.

Ghazi al-Shawashi complained that Tunisia was in a state of "complete crisis and isolation as a result of Kais Saied's destructive policies", urging a coalition of political parties, civil society organisations, and unions to oppose the president.

For Marzouki, Tunisia must reverse Saied’s moves to restore it to the democratic path, or he warns it may resemble a certain Levantine country with a history of instability and dysfunction.

“[We need] democratic resistance, the resignation and the judgment of Saied, new legislative and presidential elections, a stable government, and the resumption of the economic machine stopped for seven years ... otherwise Tunisia will be another Lebanon.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.