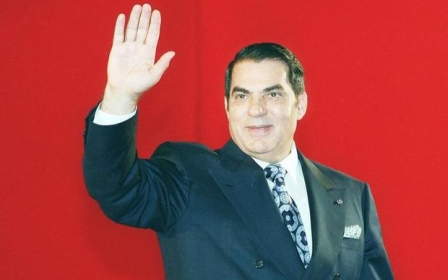

Tunisian autocrat Zine El Abidine Ben Ali dies at 83

Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, longtime Tunisian president and the first autocrat to be ousted by the wave of demonstrations known as the Arab Spring, passed away on Thursday, according to his family lawyer and Tunisia's foreign ministry.

Ben Ali died in Saudi Arabia at the age of 83, several days after reports emerged on 13 September that he had been hospitalised in Riyadh and was in critical condition.

His lawyer, Mounir bin Salha, said on Facebook that Ben Ali died in Jeddah on Thursday and that his body will be buried on Friday in Mecca.

He had lived in exile in the Gulf kingdom since 14 January 2011, one month into protests against his 24 years of rule. He is survived by his wife Leila and their three children - Nesrine, Halima and Mohamed - as well as by three daughters from his first marriage, Ghazwa, Dorsaf and Cyrine.

Ben Ali never served time in prison despite having been sentenced to jail by Tunisian courts in absentia for abuse of power, corruption and involuntary homicide.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The former ruler had largely disappeared from the public sphere since his overthrow, yet he had vowed in May 2019 to return to Tunisia. “Be assured, I am coming back, God willing,” he wrote in a letter at the time.

While reports in May had suggested Ben Ali wished to be buried in Saudi Arabia, Tunisia’s Prime Minister Yousef Chahed said in September that he would give his “green light” for the former autocrat to be buried in his home country.

A quarter-century of authoritarianism

Born on 3 September 1936 in the coastal town of Hammam Sousse, Ben Ali grew up in a middle-class household under the French colonial protectorate.

Like other Tunisian youth of the era, he was involved in the armed resistance against France and reportedly spent some time in prison.

Following Tunisia’s independence in 1956, he joined the newly formed army and over the following decades would climb up the ranks, serving as military intelligence chief and director-general of national security.

In the 1980s, he was named the minister of defence, interior minister and eventually prime minister by Habib Bourguiba, the "founding father" of independent Tunisia.

But in November 1987, a mere year after becoming premier, Ben Ali toppled Bourguiba in a bloodless coup after doctors declared the then-president to be incapacitated, at a time when the country’s economy was struggling under high inflation and debt.

Over the next two decades, Ben Ali maintained a strong grip on the presidency despite his initial vow to further democratise the country’s political system.

While he nominally granted more freedom to the country’s political opposition, electoral rules in effect guaranteed that his Democratic Constitutional Rally (RCD) party would stay in power.

Over the course of five presidential elections, Ben Ali won between 89 and 99.4 percent of the vote - casting serious doubts over the legitimacy of the results.

Press freedoms, meanwhile, were non-existent, with strict censorship rules imposed on the local press and journalists arrested and imprisoned for criticising the president.

In 1992, French news channels were blocked from broadcasting in the country when Ben Ali’s brother Habib was tried in absentia for money laundering.

As a result, Tunisia under Ben Ali was consistently ranked poorly by international barometers of human rights, democracy and press freedoms. In 2010, Reporters Without Borders slammed Tunisia for its “policy of systematic repression enforced by government leaders in Tunis against any person who expresses an idea contrary to that of the regime”.

While the Tunisian economy thrived under certain metrics under Ben Ali, the country’s youth, particularly in impoverished and rural areas, struggled with high unemployment.

The self-immolation of street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi on 17 December 2010 over economic hardships was the spark that launched the revolt against Ben Ali’s authoritarian rule and inspired other popular movements across the region and the world.

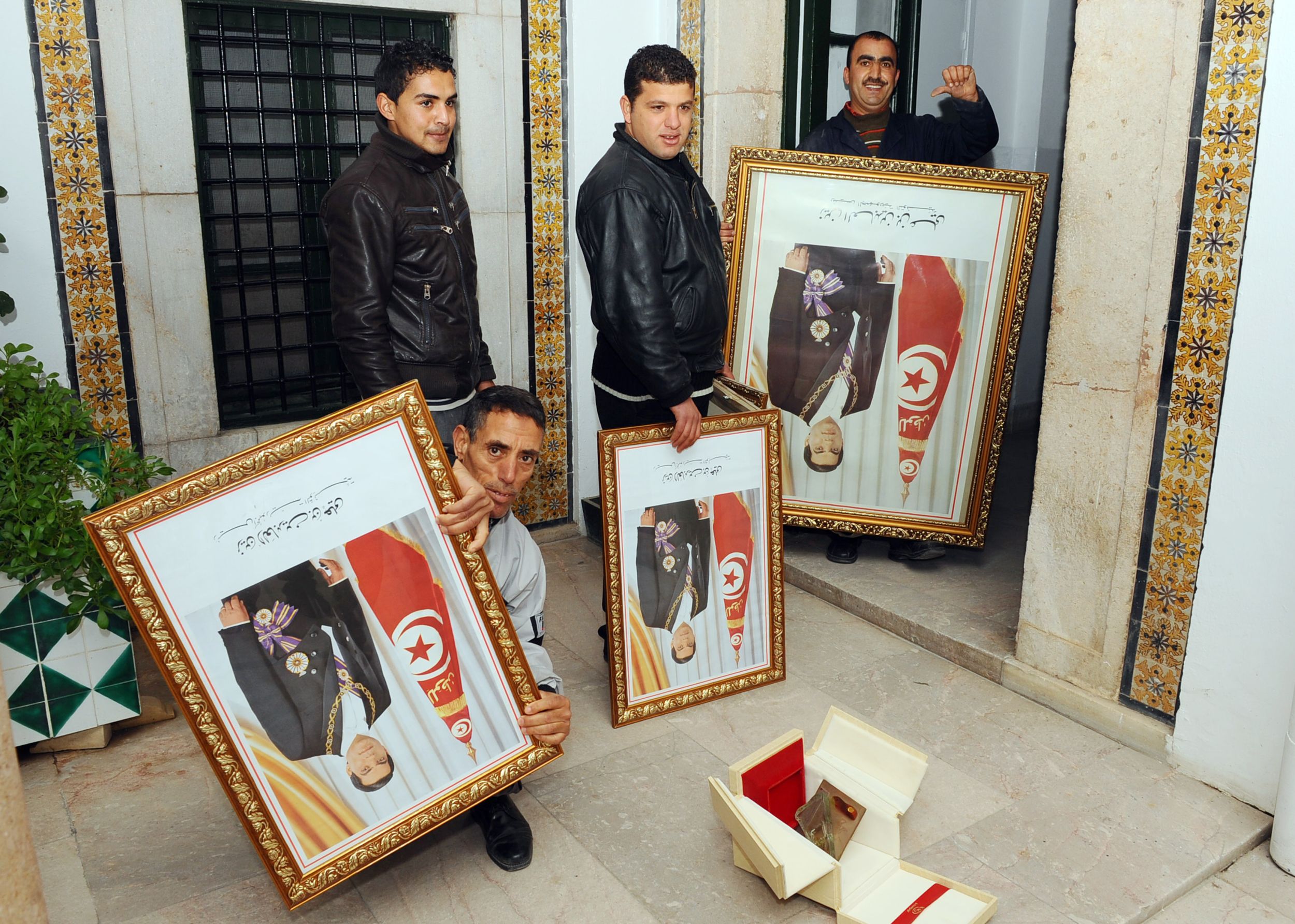

The aftermath

Nearly nine years after Ben Ali’s downfall, Tunisia is a very different place.

There have been distinct - if fragile - efforts to bring about accountability for the crimes and misdeeds committed by the Tunisian state under Ben Ali.

Meanwhile, Ben Ali and a number of associates have been tried for corruption, as well as for the use of deadly violence against protesters, although some sentences have been slammed for being too lenient.

In 2011, Ben Ali and his wife were sentenced to 35 years in prison and tens of millions of dollars in fines for theft and unlawful possession of drugs, weapons, archaeological artefacts and foreign currency.

A year later, Ben Ali would receive a life sentence - once again in absentia - over the killing of 43 protesters during the uprising. He never spent a day in prison for his crimes as president.

While the country still struggles with economic and security issues, it is widely perceived as the most successful transition to democracy post-Arab Spring.

Ben Ali’s death comes mere days after the first round of voting in a presidential election set after the death of President Beji Caid Essebsi in July.

Whoever wins in a second round of votes will become Tunisia’s second freely elected head of state since the country’s independence.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.