Turkey's love affair with currency swaps explained

Since 2018, when the lira began suddenly fluctuating against the US dollar, the Turkish government has sought currency swap deals with other countries in an attempt to relieve pressure on the G-20 country's currency.

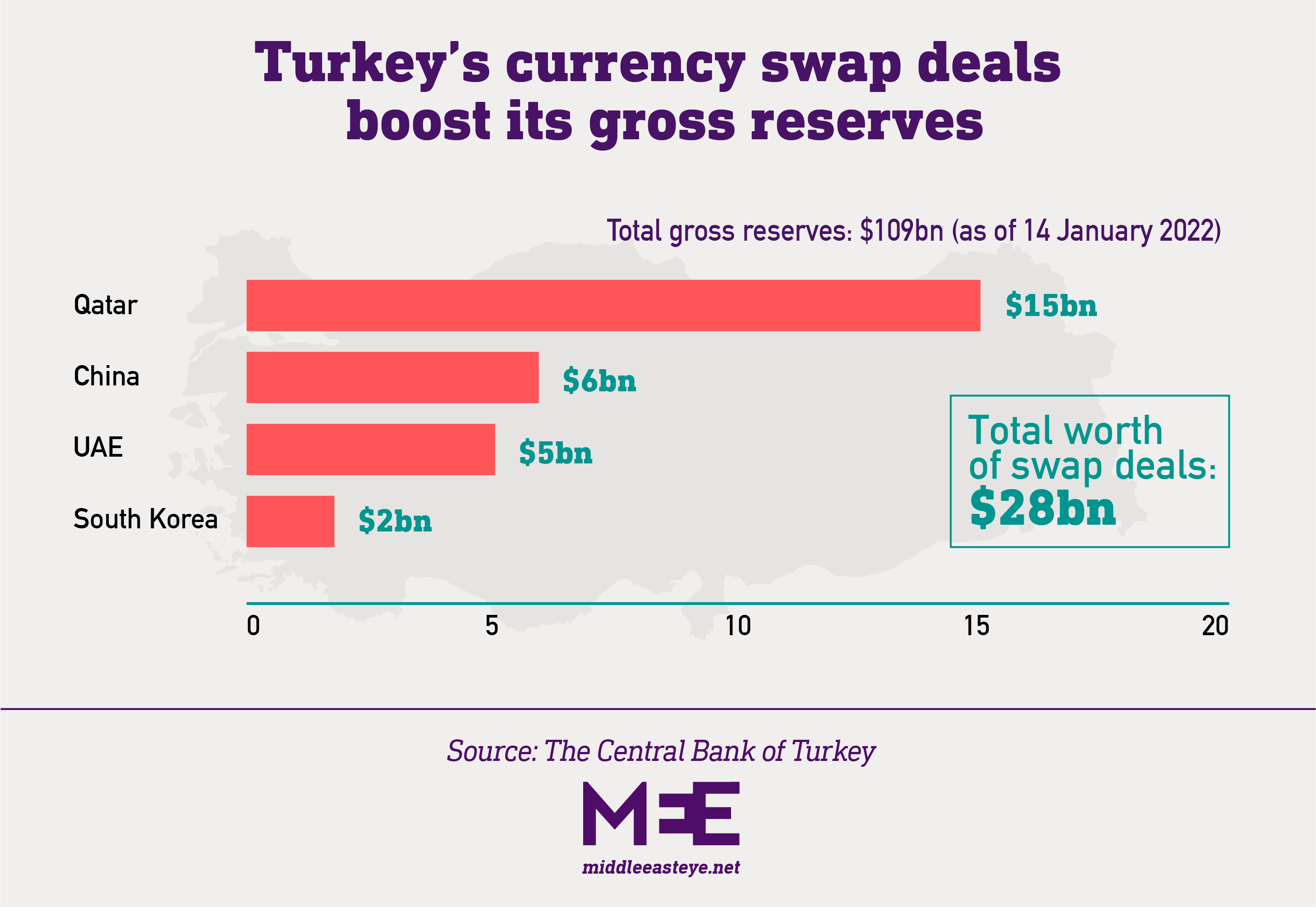

With last week’s $5bn currency swap deal with recently rekindled partner the United Arab Emirates, Turkey’s latest swaps now total around $28bn. Another swap or deposit deal with Azerbaijan worth €1bn is on the way. Anakara has also previously secured deals with Qatar, China and South Korea.

Here's what you need to know about Ankara's financial scheme:

What is a currency swap deal?

It is basically a decision by two or more countries to use their respective local currencies in trade and international business payments, so they don’t need to spend internationally recognised reserve currencies such as dollars and euros.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

For example, in the case of the Turkey-UAE swap deal, Abu Dhabi opened a lira account at the Turkish Central Bank, and Ankara opened a dirham account at the Emirati Central Bank. A nominal 18bn dirhams was placed in the UAE and its equivalent of 64bn lira in Turkey, to be kept there for a slated period of three years.

“Each country advances a loan in local currencies to each other to be used in the future to avoid [using] international reserve currencies such as the US dollar or euro,” says Kerim Rota, a veteran senior banker and a politician with the Turkish opposition Future party, known as Gelecek. “Now if they want, each country can make the payments required for investment or bilateral trade in local currencies."

According to Rota, the various parties in these swap deals have barely touched the funds allocated for trade.

“I heard that really small amounts have been utilised, like a $3-5m level,” he tells Middle East Eye. “It is a political gesture by countries like Qatar and China to Turkey. There isn’t any cost to them.”

Why would Turkey make the deals?

The root cause is Turkey’s depleted foreign currency reserves, which is mainly driven by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s crusade against high interest rates.

The Central Bank consumed its reserves in 2019-2020 by selling around $128bn to stabilise the lira against the dollar.

In December last year, following a series of interest rate cuts, the bank also spent $17bn in direct and back-door sales through the public banks, to cool off foreign exchange demand by citizens who were fleeing the lira to protect themselves against soaring inflation, which hit 36 percent in 2021. The lira shed 44 percent against the dollar last year alone.

“These kinds of swap deals help the Turkish Central Bank to boost its gross reserves,” Rota says. “Considering Turkey’s external debt refinancing needs, it is just a drop in the ocean.”

'These kinds of swap deals help the Turkish Central Bank to boost its gross reserves. Considering Turkey’s external debt refinancing needs, it is just a drop in the ocean'

- Kerim Rota, veteran senior banker

For example, the Central Bank’s gross reserves, as of 12 January, are $109bn, and of that amount $28bn belongs to swaps with the other countries.

However, in recent months Ankara’s steps to sign more swap deals with other countries hasn't created the impact in the markets the government hoped for. That's because the Central Bank also has forex swap deals with local Turkish banks. And when you exclude those swaps, the net reserves fall below zero, to minus $56bn.

Official statistics indicate Turkey has $124bn in short-term debts that will mature in the next 12 months, which will need some of the Central Bank reserves to be paid.

Rota says the swap deals only have a psychological impact on the markets to calm the rising dollar, but that impact also has run its course.

“Now imagine, the Turkish Central Bank has a $28bn debt under swap deals,” he says. “Before 2018, the bank didn’t have any debts to pay, because the loans are generally taken by the treasury, not by the bank.”

The government is also aware that you can’t get that much out of the swap deals. That's why Erdogan last month laid out a foreign exchange denominated deposit scheme to attract Turkish investors and stem the dollar demand.

“I’m not very optimistic about the near future,” Rota says. “These measures will give three to four months to the government. And then it will hit us back.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.