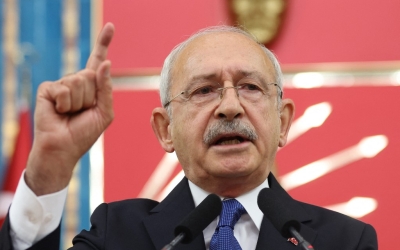

Who is Kemal Kilicdaroglu, the man charged with removing Erdogan?

On Monday, after a few days of drama within the Table of Six opposition coalition, Kemal Kilicdaroglu was officially announced as the alliance’s presidential candidate and the man charged with taking on Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

The 74-year-old will be running for the post for the first time in his life, with Turkey set to go to the polls on 14 May.

As chairman of the Republican People’s Party (CHP), Kilicdaroglu has helped transform the party that founded the Republic of Turkey from a secularist, establishment political organisation to one that is diverse, socially democratic and centre left.

With Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party dominating the political scene for decades, Kilicdaroglu has sought to establish alliances with other opposition parties, and attempted to extend his reach beyond traditional CHP voters.

In 2019, he was the architect of a plan to take the fight to the AKP, which resulted in local elections that removed the ruling party’s mayors from several major cities, most prominently Istanbul and Ankara, which it had held since the 90s.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Born in the remote Anatolia village of Ballice in Tunceli, Kilicdaroglu had humble beginnings in an impoverished family that claims descent from the Prophet Muhammad. His father was a civil servant who struggled to earn enough for his family of seven children.

Kilicdaroglu has previously recalled walking to school with bare feet in the summer, wearing clothes riddled with holes.

Despite his financial difficulties, he was a good student, top of the class and the school, who eventually studied finance and entered the public service as a tax inspector in 1971.

A member of the historically persecuted Alevi sect, Kilicdaroglu was a member of leftist political organisations until the beginning of his career in the civil service, which included a stint as general manager of the Social Insurance Institution (SSK), which handled health and insurance services on behalf of the Turkish public.

Yet his experience at the SSK has not always proved to reflect well on him. Erdogan continues to raise Kilicdaroglu’s time at the institution, claiming his mismanagement bankrupted the social security system.

The CHP leader retorts he was simply a bureaucrat who didn’t make the laws, and argues that the age of retirement, which was 33 in the 90s, bankrupted the system, rather than any actions he made.

After retiring from the civil service, Kilicdaroglu was recruited to the CHP, which was attracted by a report he wrote suggesting ways to prevent corruption in the public sector.

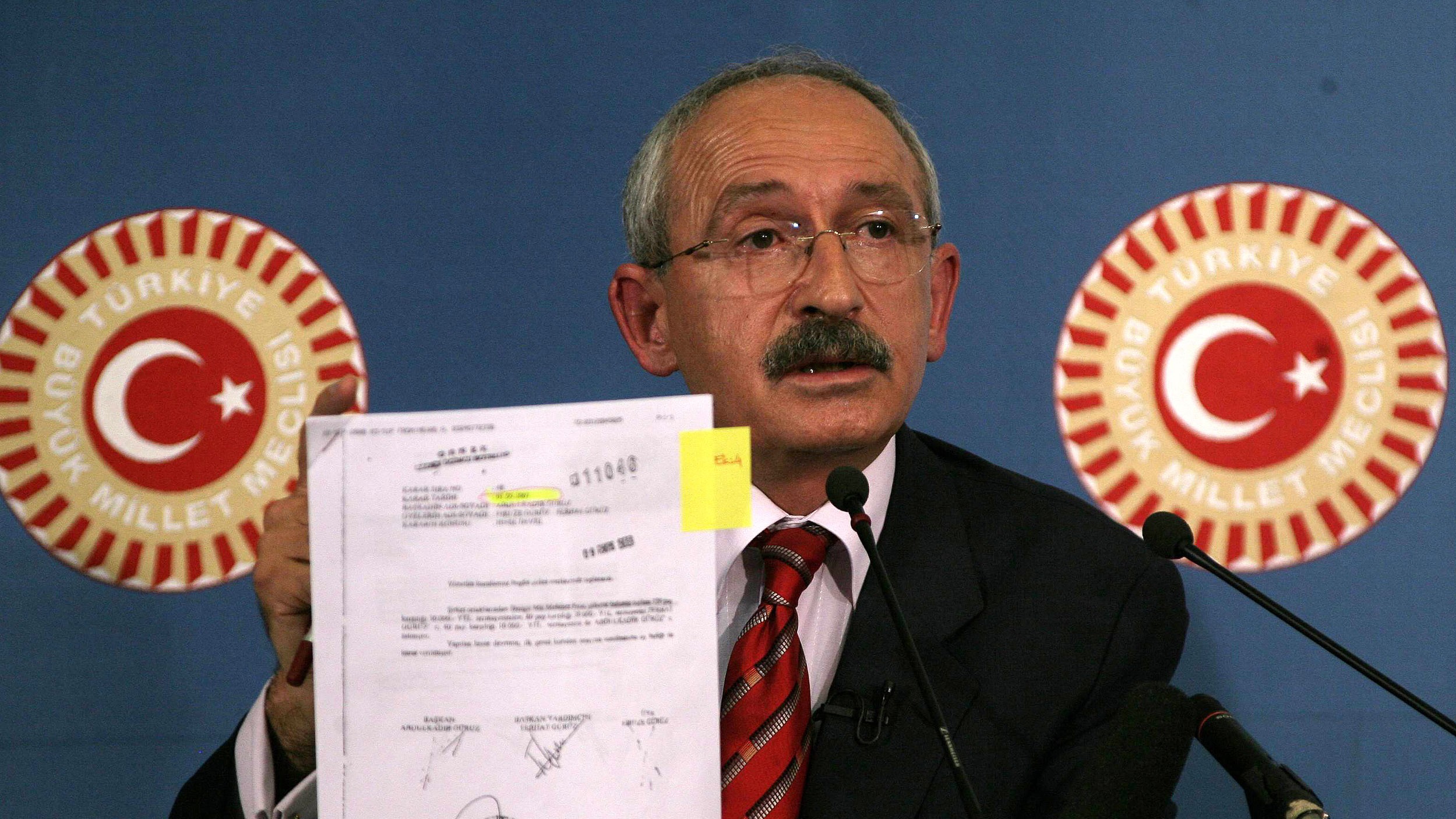

In 2002, Kilicdaroglu was elected to parliament. Soon he gained prominence and popularity by raising corruption allegations against AKP heavyweights such as Saban Disli and Dengir Mir Mehmet Firat in 2008.

Both were forced to resign from their senior posts within the party after Kilicdaroglu’s revelations, which at times he delivered during televised debates with Firat, who struggled to defend himself when confronted.

Kilicdaroglu ran for Istanbul mayor in 2009. Though he increased the CHP’s vote by 25 percent, he lost the election, making gaffes along the way by mispronouncing Istanbul districts. It didn’t help that he’d never lived in the city until he ran to be its mayor.

Leading the CHP

In an unexpected turn of events, Kilicdaroglu became the chairman of the CHP in 2010, after his predecessor Deniz Baykal was forced to resign due to the leak of a sex tape.

Since then, he has been trying to expand the CHP’s grassroots by changing the fabric of the party.

Those close to him named his policy “Kilicdaroglu politics”, where there is an absolute belief that Erdogan could be beaten only through a diverse alliance where competing ideological factions must come together under the minimum requirement of a democratic and pluralistic society.

“We are social democrats,” he said. “Left and right, these are outdated 18th-century concepts. We can reach an understanding with anyone that loves their country.”

Kilicdaroglu started the change by adding politicians to the party from the pro-Kurdish opposition and Islamist movements, traditionally arch-enemies of the CHP, whose only aim used to be safeguarding the secular establishment dominated by an elite of judges, generals and high-ranking bureaucrats.

One landmark policy was dropping the party’s opposition to women wearing headscarves in universities and public offices, and also ending the fight with the government over religious expressions of belief. The CHP was moving from the Kemalist and Jacobin ideological line to a more open and pragmatic attitude.

In a radical step, in 2014, he established an electoral alliance with the Turkish nationalist MHP, which during the 1970s was a fierce CHP foe during a time when nationalists and communists killed each other seeking regime change.

Both parties nominated Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu, a nationalist with Islamic roots, for the presidential election. The choice angered the CHP’s traditional grassroots, a feeling backed by some CHP members of parliament.

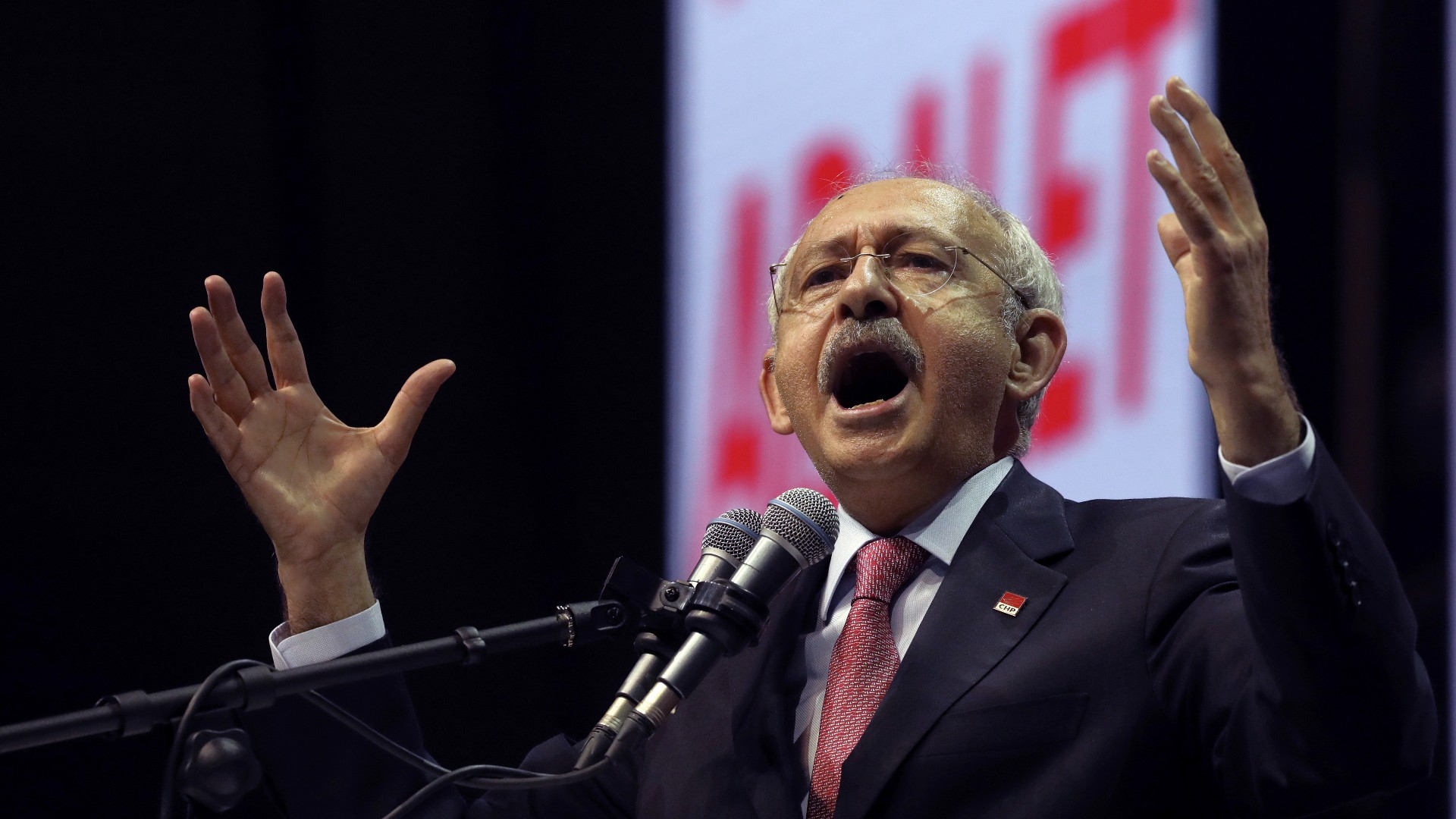

The dispute reached a tipping point at a meeting with the dissidents hosted by Kilicdaroglu, where he exploded. “If you live in this country, you have a responsibility to your children. You will go to the ballot box like a man, you will do what is necessary for democracy and you will not allow a dictator to elect a president,” he reportedly shouted at them while smashing his fists on a lectern.

Erdogan won the elections but Kilicdaroglu didn’t change his strategy. He continued to engage with the MHP and silently backed the pro-Kurdish People’s Democracy Party (HDP) to run for the parliamentary elections the following year, which he hoped would deny the AKP a majority.

Previously the HDP and its predecessors ran independent candidates for parliament, but for the first time they ran candidates as a party and passed the 10 percent threshold needed to enter parliament.

As predicted, the AKP lost its majority and was forced to begin building a coalition to govern. The opposition’s victory was short-lived. A few months later, snap elections were called and the AKP regained its majority amid spiralling terror attacks and violence meted out by Kurdish and Islamist armed groups.

Other events disrupted Kilicdaroglu’s strategy. The attempted military coup of 2016 upended the political scene and handed Erdogan a pathway to transforming Turkey’s parliamentary system into a presidential one.

Kilicdaroglu himself wasn’t immune to the turbulence. During a 2016 visit to the Black Sea, he was caught up in an attack claimed by the Kurdistan Workers’ Party armed group that killed a gendarmerie officer.

As Erdogan oversaw a sweeping crackdown following the coup attempt, including mass dismissals from state institutions and the weaponising of the judiciary, Kilicdaroglu launched “a march of justice” from Ankara to Istanbul, walking for 25 days chanting “right, rule of law and justice”.

Thousands of people from different political and social backgrounds joined Kilicdaroglu, who eventually held a large rally in Istanbul to showcase his politics of alliances.

Spearheading alliances

In 2018, Kilicdaroglu spearheaded another electoral alliance with Turkish nationalist breakaway party leader Meral Aksener and long-standing leader of the Islamist Felicity Party, Temel Karamollaoglu. Kilicdaroglu, again stunning his party members, proposed former Erdogan associate Abdullah Gul to run as a joint candidate for their front, which they called the Nation Alliance.

Aksener was not convinced to back the project, however, and Erdogan won another term against the CHP’s Muharrem Ince, a Kilicdaroglu critic who had to leave the party following a crushing defeat. Kilicdaroglu then began to purge his party of his critics, the old-guard Kemalists that opposed working with different opposition parties.

Meanwhile, Kilicdaroglu continued his broad tent approach. The following year, he put out feelers to different political and social groups and met the pro-Kurdish HDP leadership. His agenda: to run joint mayoral candidates in Istanbul, Ankara, Antalya and other major urban centres.

The HDP agreed to the proposal, and despite not officially being part of the Nation Alliance, didn’t nominate its own candidates in cities the opposition was targeting.

Kilicdaroglu picked relatively controversial names as candidates. In Istanbul, he ran Ekrem Imamoglu, a relatively unknown figure whose only success was managing a district municipality. Imamoglu came under severe criticism, and was accused of behaving like a right-wing, conservative politician.

In Ankara, he selected Turkish nationalist Mansur Yavas, whose past made many within the secular establishment uneasy. The Nation Alliance won the major cities, including Istanbul, Ankara and Antalya, in 2019.

After the election victory, Kilicdaroglu was publicly assaulted and a mob tried to lynch him in rural Ankara, when senior Turkish officials like Defence Minister Hulusi Akar were present. As the CHP leader attended the funeral of a soldier who was killed by the PKK, relatives of the slain man attacked Kilicdaroglu, who took refuge in a house and later was saved by the security forces.

The government had been accusing Kilicdaroglu of working with the PKK through an alliance with HDP, charges he dismissed as a conspiracy.

Other liberal and conservative parties began to be enlisted by Kilicdaroglu, such as former prime minister Ahmet Davutoglu’s Future Party, as well as former deputy prime minister Ali Babacan’s Deva Party.

The Table of Six

Together, the opposition alliance became known as the Table of Six.

The Table of Six announced a series of programmes, including constitutional amendments to revert the political system to a parliamentary one and a plan to reform Turkish democracy.

Kilicdaroglu’s foreign policy is relatively unknown, but those close to him say the government under his leadership would reorient Turkey back to the West while maintaining a balanced approach with Russia.

Kilicdaroglu is also expected to escalate a normalisation with Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad while looking for ways to return a huge chunk of the nearly four million Syrian refugees back to their homeland on a voluntary basis.

Kilicdaroglu last year said he would hold Israel, Saudi Arabia and Greece accountable for the steps they have taken against Turkey in recent years, promising to backtrack from Ankara’s recent policies that have sought detente with its regional neighbours and competitors.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.