Turkey elections: What is the opposition’s Russia policy?

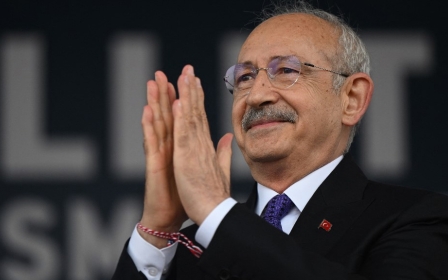

However much US President Joe Biden may wish it, Turkey is unlikely to change the broad outlines of its policy towards Russia if the opposition candidate Kemal Kilicdaroglu captures the presidency on 14 May.

For one thing, much of that policy is set on tram lines. The incumbent president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, will activate the first phase of the Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant on Thursday, which is being built and operated by Russia. The opposition have vowed not to close it.

Similarly, opposition foreign policy specialists interviewed by Middle East Eye praised the agreement securing the passage of grain from Ukraine that Erdogan's government negotiated in its role as Black Sea mediator. Nor would a Kilicdaroglu-led government join western sanctions against Moscow.

Nonetheless, since 2016 Erdogan has deepened Turkey’s already-rich ties with Moscow, and has raised eyebrows in the West with steps like purchasing the Russian S-400 missile system and cutting energy and trade deals.

So what kind of Russia policy would Kilicdaroglu’s government and the coalition of six parties that backs him carry out?

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Many in the West expect Turkey to turn increasingly anti-Russia and join the sanctions imposed on Moscow since the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Mixed signals

The signals coming out of Kilicdaroglu’s own mouth have been mixed. That suggests Kilicdaroglu doesn’t have an outright anti-Russia policy, but more of a nuanced take.

“While western countries have not provided many technologies to Turkey, Russia did,” Kilicdaroglu said in October while paying a visit to Washington. “For example, Russia has provided technology in areas such as aluminum, the glass industry, the petrochemical industry. But Turkey also has developed that technology, it has become more perfect. We will maintain our economic relations [with Russia].”

What Kilicdaroglu references is the USSR’s investments in Turkey following the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire. The Soviets extended credit to Turkey in the 30s and 50s, helping it establish some of the first factories in the post-Ottoman era, and later set up Iskenderun steel factory, Seydisehir aluminum factory, and petrochemical plants in the 60s. All became essential for the Turkish economy and its industry.

“We think that we should stand by Ukraine in the Russia-Ukraine war,” Kilicdaroglu said. “It is not right for a nuclear-armed country to invade the territory of a non-nuclear-weapon country, to start a war.”

Turkey, under Erdogan, has done exactly what Kilicdaroglu suggested.

'I’m afraid to say Turkey has been quite successful in its Russia policy since the invasion'

- Turkish opposition official

Ankara condemned the Russian invasion on every international level, and voted with the Nato bloc in the UN against Moscow. It delivered weapons to Kyiv, from simple armour to sophisticated armed drones and laser-guided missiles. It facilitated prisoner exchanges and mediated a landmark grain deal which is functional to this day. It also hosted Ukrainian and Russian foreign ministers in Antalya for ceasefire talks.

However, Turkey pointedly refused to joint western sanctions. It accepted Russian refugees, sold citizenships to them, and largely allowed trade with Moscow. Russian airplanes and ships still freely visit the country, bringing tourists and cash.

“I’m afraid to say Turkey has been quite successful in its Russia policy since the invasion,” one senior Turkish opposition official told MEE. “The grain deal, for example, is a major achievement that possibly stopped a food crisis.”

The opposition official said Ankara also managed to prevent Russia from infiltrating the Turkish banking system and largely succeeded in stopping Russian moves to circumvent sanctions through Turkish companies.

“After the elections, we will put more work into the grain deal to make sure the Russians are happy about their own wishes,” the official said, referring to Moscow's displeasure over the lack of progress in Russian food and fertiliser exports through the Black Sea. “We will continue to put our hands under the stone,” the official added, using a Turkish idiom that could be translated as "we will do our part".

The official said Turkey, under a Kilicdaroglu government, would re-institutionalise its relations with Russia but continue to promote dialogue and engagement between Moscow and Kyiv through diplomacy. “Turkey has been very neutral towards the USSR in the past, why can’t I do it now?” the official said, adding that Ankara will continue to uphold the Montreux Convention that governs the passage of vessels to the Black Sea and deny the transit of all warships to there.

Longstanding ties

A second senior Turkish opposition official said that Russia-Turkey relations are older than some of the western powers’ national history, and Ankara has concrete experience in dealing with Moscow going back centuries.

“We are over-dependent on Russia and of course we won’t try to antagonise them,” the second official said. “We won’t do things like buying another S-400 system from them or throwing them another contract for a nuclear power plant, but we will be balanced.”

Both officials said Ankara wouldn’t join the western sanctions but also won’t allow them to be circumvented through Turkey.

Kilicdaroglu, in an interview last month, said under his leadership Turkey would only follow sanctions on foreign countries voted through by the UN Security Council.

“The position of Russia in Turkish foreign policy is clear,” Kilicdaroglu said in the same interview. “On the basis of mutual respect, I do not think there is a reason for this situation to change. On the contrary, I believe that existing positions will be further consolidated rather than facing new challenges.”

Like top officials in Erdogan’s administration, opposition sources express concern about a forthcoming Ukrainian counteroffensive and spoke about the need for a face-saving solution for both sides. In doing this, they are veering off Nato’s script.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said he will accept nothing less than the return of all territories Kyiv previously held.

Both opposition officials added they were worried that a Ukrainian counteroffensive would be counterproductive and wouldn’t result in genuine progress other than shedding more blood.

“Russia isn’t easy to defeat and history teaches us they can survive very long,” the first official said. "This war can expand to a regional and global conflict. It is quite dangerous, we will have to prioritise efforts to resolve it.”

The official said everyone needs a face-saving solution. “Russia needs a respectable defeat and Ukraine needs a considerable victory,” the official added. “I’m sorry to say it, but [for Ukraine] it may not include Crimea. And there needs to be administrative solutions for the areas in the east, like Donbas.”

The opposition officials say the West needs to find a solution where Russia is once again incorporated into the European security architecture. “We need a stable architecture and we cannot leave Russia out of the picture,” the first official said.

Russian president Vladimir Putin in recent years established a personal rapport with Erdogan, pumping billions of dollars to Turkish Central Bank through Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant last year, which helped stabilise the Turkish lira months before the elections.

Yevgeny Prigozhin, the head of Wagner group Russian private paramilitary that is closely linked with Putin, told Turkish Eurasianist daily Aydinlik this weekend that Erdogan is a courageous and strong-willed leader “who developed his own national agenda”.

“He is seizing more territories, taking them under Turkey’s control, and no doubt doing the right thing with respect to national greatness,” he said. “Hence, his aim is to establish an Ottoman Empire, and ours is extending Russia’s reach in the world from Alaska to South Africa.”

Asked about possible help to Erdogan from Putin to win the elections, Kilicdaroglu said in the interview last month that he also hears similar comments but he doesn’t want to believe that it reflects the truth.

“The most important element of relations between Turkey and Russia should be trust,” he said. “It is necessary not to interfere in one another’s internal affairs, and especially not to take sides in matters such as elections or be interpreted as such,” he added.

“Russia is also a country that frequently expresses its discomfort with the interference in the internal affairs of countries and is aware of the gravity of the steps in this direction. An opposite behaviour erodes and destroys mutual trust.”

The second Turkish opposition official said everyone would re-adjust themselves if Kilicdaroglu captures the presidency, the Russian leadership included.

“There are signs that the Russians are now rethinking their position and concerned that they put all their eggs in one basket,” the official said, smiling.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.