Turkey's economic crisis: Is it down to 'foreign agents' or mismanagement?

ISTANBUL, Turkey - Heard before they are seen, tucked away in a cluster of alleyways on the fringes of the Grand Bazaar, Istanbul’s famed money traders sit in huddles, juggling phones and jostling for attention.

The droning racket they make as they out-shout each other to announce the latest dollar exchange rate intrudes on the general sleepiness of their surroundings, brought on by anxiety about the economy, the lack of tourists and Ramadan-induced grogginess.

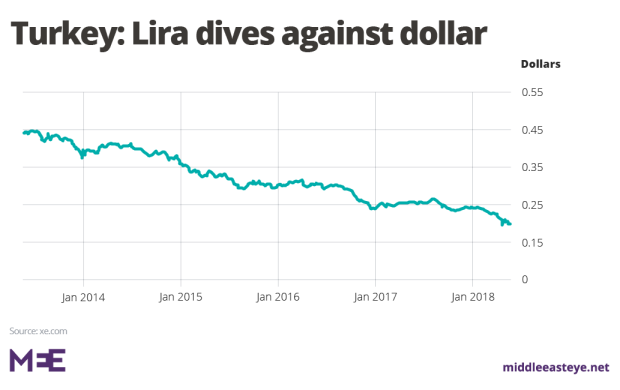

The news delivered by the “pushcart stock market”, as the marketplace is known, has taken on more significance in recent months as the country battles the historic lows the Turkish lira has been hitting because of deepening economic trouble.

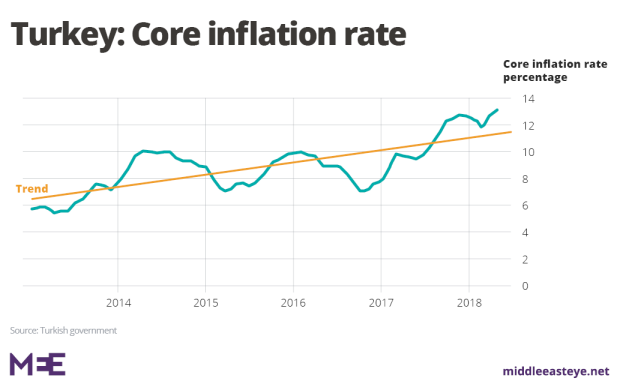

Economic success has bolstered President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) through 16 years of electoral success. But ahead of momentous presidential and parliamentary elections on 24 June, that record is being undermined by surging inflation and interest rate hikes aimed at containing the currency's instability.

While the opposition blames the current symptoms on the shortfalls of an economic programme that sacrificed industry and trade for an internal construction boom, the government has insisted the source lies elsewhere, with “foreign agents”. One of the election’s key battles may be over which telling of Turkey’s economic story resonates most with an electorate adapting to new hardships.

Despite being a middleman between customers and difference exchange bureaus, relying on the currency rates, he saw no fault in the government’s economic strategy.

“This is a scheme to undermine Turkey’s success and influence the election results,” the trader, who had spent his whole working life in the market, told Middle East Eye. “They are doing what they did to Iran and Russia.”

Though he would not name which countries he believed were behind the alleged scheme against Turkey, Abdulrahman was convinced an external power with billions of dollars in Turkish markets had maliciously withdrawn them to hurt the currency.

“World leaders talk very differently [than in the past]. In the old times they were serious, they were thinking twice before talking about something. Now in other parts of the world, someone makes a stupid statement, says something really reckless and it affects this market,” he said.

He and other Erdogan and AKP supporters believe in a narrative of unprecedented economic development in Turkey; bridges and tunnels connecting Europe and Asia in Istanbul, the modernisation of neglected neighbourhoods and airports that link disparate cities in a country of unwieldy size and terrain.

“It was just a temporary heaven and now he can take us to an economic hell,” opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) lawmaker Aykut Erdogdu, a former civil servant in Turkey’s treasury, told MEE.

Erdogdu said the AKP economic programme was fragile, increasing Turkey’s debt, privatising national industries and failing to distribute income fairly.

While gleaming shopping malls and new developments have sprouted as apparent markers of prosperity in parts of Istanbul and Ankara, Turkey has consistently remained one of the most unequal of the 37 high-income countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Learning to sacrifice

Amid the stalls selling discounted fresh produce from around Turkey that form the vast weekly food market in Istanbul’s conservative, working-class Fatih neighbourhood, many have learned to leave items out of their baskets - meat for many, carrots for some and even the cheeses and olives essential to traditional Turkish breakfasts.

Other than food, we cannot buy anything

- AKP supporter

Pushing further into the market, one woman makes it known that without work she cannot afford the produce. She points to the narrow passages between the stalls, where she scavenges for items that have fallen to the floor.

“If I used to buy two kilograms, I now buy one... other than food, we cannot buy anything,” said another shopper, who did not want to be named. Like others in the market, she believed the prices were being pushed up by interfering “foreign agents".

“We should ask why they don’t want this government in power,” she said.

Even more middle-class shoppers in the more specialist markets of nearby Eminonu are being squeezed, though they directly blame the government."We have to be so careful when we go shopping because we don't know what's going to happen next. That's why if you buy something, you carefully consume it to make it last longer. We didn't used to think like this because food was relatively cheap,” said a 48-year-old architect from a suburb in Anatolian Istanbul, visiting the historical district for shopping.

It is precisely because of the economy that she feels the government needs to change, accusing it of not making enough of Turkey’s own resources.

“Turkey has resources, mines and even some petrol but we don't process them, we just give them to foreigners and they do the process and we buy them back,” she said. “We don't have agriculture, we don't have industry, for the past 16 years our money just goes into concrete - this construction madness, not production or manufacturing.”

The government has sought to remedy some of the problems ahead of the election. Concerns about manufacturing were met with Erdogan’s promise to build five new industrial zones that would provide 100,000 jobs across the country. What was considered a complicated monetary policy was simplified to encourage investment and control the currency.

“Erdogan knows too well that it is indeed 'the economy, stupid' that will play a major role in voter sentiments come the elections on June 24,” wrote business journalist Mushtak Parker in the pro-AKP Daily Sabah newspaper, referring to former US president Bill Clinton's famous phrase.

“Erdogan is seen as a populist president whose main constituency of supporters are conservative hard-working people and professionals. Competence in economic management has become the mainstay of democratic politics in recent decades.”

Souring international relations

While Erdogan has himself promoted the idea that foreign powers meddling in Turkish politics have sowed division within the country, his opponents accuse the president of sabotaging international relationships he relies on for an economic programme that relies on investment.

Erdogdu said Erdogan’s fights with Germany and other EU countries do not help and investors have also been spooked by mass arrests of alleged supporters of US-based cleric Fethullah Gulen, blamed for a 2016 coup attempt.

“They are afraid he will seize the assets of businessmen because of FETO allegations,” he said.

He also accused Erdogan of selling off Turkey’s industries to foreign companies, stripping the state of its assets for the appearance of economic prosperity while Turkey’s foreign debt reached an all-time high of $453bn in late 2017.

“On one side he’s fighting Western countries, on the other side he’s begging from the Western countries,” he said.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.