Turkey's media raids threaten to silence serious dissent

On 28 October, three days before Turkey's general election, riot police broke into the headquarters building of two of the country's major newspapers.

Using tear gas and water canons to break through a line of protesters – including journalists from the newspapers, who had assembled to try to resist the raid – armed police stormed the Koza İpek building in Istanbul's Sisli neighbourhood, took over the newsrooms of the opposition dailies Millet and Bugun, and cut the live broadcasts of Bugun TV, Kanalturk TV, and Kanalturk radio, which were transmitting from the same building.

Speaking to viewers moments before the police entered the studio and pulled the plug, editor in chief of Bugun TV Tarık Toros described what he thought was happening.

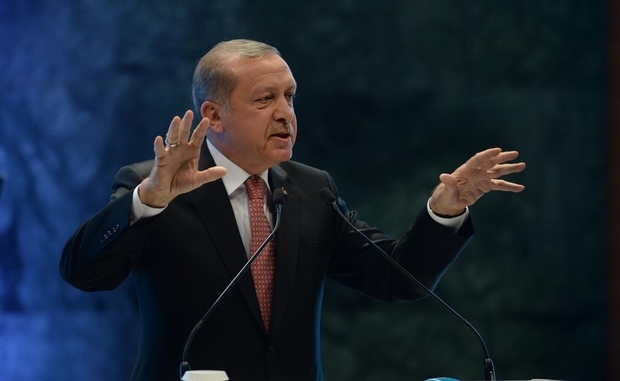

"This is an operation to silence all the dissident voices that the ruling party does not like, including media outlets, opposition parties and businessmen,” Toros said on air, referring President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's Justice and Development Party (AKP). “This is true for anyone who does not obey."

After the broadcast was cut Toros was forcibly ejected from the building.

The following day, trustees who had been appointed by the state to take over the two newspapers were escorted into the central newsrooms by police officers. At their head was Hasan Olcer, who told Bugun reporters that the issue they had prepared the day before, which had been seized by the police, had been “a disgrace”. Anyone who objected was insulted and told to get out, or their names were taken down. In total, 71 journalists were fired.

The papers have continued to publish, but their content has now drastically changed and their editorial lines have become pro-government. On 11 November, Turkish police also organised a night raid on the Istanbul offices of Feza Publications, which prints the Zaman newspaper, for printing alternative versions of Bugun and Millet called “Free Bugun” and “Free Millet” that were being compiled by the fired staff of the papers.

Millet and Bugun were stormed by the police because they are owned by Koza İpek Holdings, a conglomerate said to be linked to the US-based Turkish cleric Fethullah Gulen.

Gulen, who was once a key ally of President Erdogan, is now considered by the AKP to be the leader of a terrorist group it calls the “parallel state structure” because, the party claims, it had infiltrated powerful state institutions.

Following the raid on Koza İpek, Kaynak holdings, the owner of another publishing house linked to Gulen, was also taken over by trustees accompanied by police on 18 November. Gulen is not recognised as a terrorist outside of Turkey.

The storming of the Koza İpek owned media was no one-off event. Turkey has always been a difficult place for the press, and it has repeatedly topped rankings as the leading jailer of journalists (including as recently as 2013). But in the last year the press has been facing state pressure at a level unseen for decades, according to journalists and human rights defenders.

Not all of those affected have been linked to Gulen. Koza İpek's offices have been raided with varying degrees of force three times in the last two months, but press from across Turkey's political spectrum – if they are critical of the government – have been targeted in an ever worsening clampdown.

“The situation in Turkey is deteriorating, with unacceptable pressure on the press and social media,” said Nils Muiznieks, commissioner for human rights at the Council of Europe.

According to Andrew Gardner, Turkey researcher for Amnesty International, in 2015 there has been a clear and very worrying deterioration in press freedom even from an already low watermark.

“Since Erdogan assumed the presidency a huge number of cases have been brought under special provision for defamation of the president, which we didn't see in large numbers before,” Gardner told Middle East Eye.

In May 2014 President Erdogan personally filed charges against the editor of the centre-left opposition newspaper Cumhurriyet, Can Dundar, for defamation.

Then, in December 2014, the offices of the Gulen-linked English language newspaper Today's Zaman were raided and an attempt was made by the police to arrest its editor, Bulent Kenes. Kenes was arrested again this October then released after a court ruled charges against him, personally filed again by President Erdogan, were insubstantial.

In June this year, Cumhuriyet's Dundar was arrested for publishing footage that purported to show Turkey's intelligence service smuggling weapons into Syria. Once more, President Erdogan personally filed the charges, pledging that Dundar “will pay dearly, he won’t get away with it so easily”.

Erdogan has continued to file charges against journalists and other civilians for insulting him. As recently as 10 November, charges were filed by the president against a Radikal newspaper columnist, Cengiz Candar.

“First, there is a systematic attempt to silence media which speaks to conservative audiences that compete with the AKP, like the supposedly Gulen-linked media,” Amnesty's Andrew Gardner said. “Then there is the targeting of the Kurdish press – large swathes of Kurdish media, including perhaps 65 Kurdish news websites, have been targeted with blocking orders by the state telecoms agency.”

Gardner said that despite the sensitive election period coming to an end the repression measures show no signs of abating: “I'm afraid the current trajectory is very negative.”

In August, Istanbul's chief prosecutor's office indicted 18 journalists, including Dundar, on charges of "making propaganda for a terrorist organisation" by publishing photographs of state prosecutor Mehmet Selim Kiraz being held hostage by a left-wing militant group known as the Marxist Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party-Front.

The prosecutors sought over seven years jail time for each of the journalists representing the newspapers Millet, Sok, Posta, Yurt, Bugun, Ozgur Gundem, Aydınlık and BirGun. Kiraz was killed in the incident. The 18 journalists appeared in court for their first hearing on Tuesday.

The clampdown has not been limited to Turkish journalists. On 6 September, two British reporters and one Iraqi reporter from Vice News were detained while reporting on violent clashes between police and protesters in Diyarbakir. The British journalists were deported, but their Iraqi colleague Mohammed Rasool is still imprisoned and has spent the last 85 days behind bars (as of 12 November).

Days later, veteran Dutch reporter Frederike Geerdink, who was previously the only foreign correspondent based in Diyarbakir, was also deported from the country having been accused of aiding the armed Kurdish resistance group, the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), in her reporting.

The AKP usually shrugs off criticism of the treatment of journalists under its rule. On 9 November, in an interview with CNN's Christiane Amanpour, Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu said he valued freedom of the press so highly that for him it was “a red line”. President Erdogan has publicly claimed that Turkey has the freest press in the world.

Not all members of the Turkish press disagree. Mehmet Celik, a journalist at Daily Sabah, a pro-government newspaper, argues that Turkey's record on press freedom is overly criticised. “Though it has its own problems like any other country in the world, I do believe that the environment for journalists is better, not worse, than 10 years ago,” Celik told MEE.

“The media in Turkey does not have problems based on censorship due to ideological factors,” Celik said. “Rather, it has its own structural problems emerging from the ownership of the media outlets.”

According to Celik, before the AKP came to power wealthy media owners could trade the support of their publications for financial gain. He believes the AKP isn't doing this, drawing the ire of much of the press. “I think the ‘anti-government' media outlets are using the freedom-of-press card because the government is not making compromises to meet the financial interests of the media bosses.”

But cases of state repression of the press keep coming. On 4 November, Cevheri Guven and Murat Capan, both of whom are editors at the privately owned weekly magazine Nokta, were arrested in their newsroom after publishing a front-cover image deemed offensive to the president.

On 11 November, an arrest warrant was issued for Ekrem Dumanli, the former editor of Zaman, Turkey's biggest newspaper, based on charges that Dumanli was "leading an armed terrorist organisation and plotting to overthrow the elected Turkish government".

And on 13 November, 10 journalists from the pro-Kurdish DiHA agency and IMC television station were roughed up then arrested by police in the eastern province of Van.

“There is now almost no serious reporting left in Turkey, except for reporting on files leaked by either conscientious lawyers or mysterious bureaucrats,” said Ozgun Ozcer, a journalist who has worked for Taraf and BirGun newspapers. “This is a huge problem that leaves the press toothless against the government's excesses.”

One of the most pernicious effects of the Turkish government's attitude towards the press, Ozcer said, is the government media's efforts to “test the waters” on policies and government positions to prepare public opinion.

“It's not only repression, which is one thing, but the silencing of serious media and the use of pro-government press to lay out what is really state propaganda. That's very damaging for the country.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.