UK prison staff trained to identify extremists 'lacked Islamic knowledge'

Prison staff in the UK involved in developing an extremism risk assessment tool now used on young children complained that they did not receive adequate training to undertake the work and felt “unsettled” because of their lack of knowledge of Islam.

Some prison staff received just one day of training or attended a series of briefing events prior to taking part in the 2009 pilot study which involved interviewing prisoners convicted of terrorism and extremism offences.

Others attended a two-day “Islamic awareness” training workshop in order to help them effectively assess “al-Qaeda-inspired extremist offenders”, while others did their own research into Islam on the internet in their own time.

Concerns about the training were raised as part of an evaluation conducted by the UK's prison service into the development of the Structured Risk Guidance for Extremist Offenders (SRG) which was published by the Ministry of Justice on Thursday.

“The lack of training and confidence among some staff in using the approach meant that staff were, or could potentially be, being asked to work at a level beyond which they were capable or confident,” the evaluation concluded.

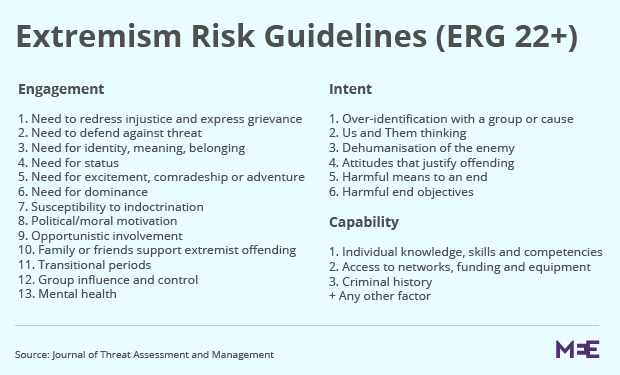

The SRG consisted of a list of 21 factors considered to be possible contributors to extremist offending. It subsequently evolved into another tool used in prisons, the Extremism Risk Guidance 22+ (ERG22+) which is also now used to assess individuals referred to the Prevent strategy's Channel counter-radicalisation programme.

Prevent is a strand of the UK government's counter-terrorism strategy, while Channel is targeted at individuals including young children who are considered to be “vulnerable to being drawn into terrorism”.Thousands of people, including hundreds of children, have been referred to Prevent since the introduction of the Prevent Duty in 2015 which placed an obligation on public sector workers including teachers and doctors to “have due regard for the need to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism”.

But concerns about reliability and validity of the ERG22+ have been raised by psychiatrists and academics who said last year that the assessment tool had “not been subjected to proper scientific scrutiny or public critique”.

Last year, the Royal College of Psychologists called on the government to publish evidence on which the ERG22+ had been based, and said current tools and methodologies should be viewed with considerable caution.

“Public policy cannot be based on either no evidence or a lack of transparency about evidence. The evidence underpinning the UK’s Extremism Risk Guidance 22+ and other data relating to this guidance should be comprehensively published and readily accessible,” it said in a position statement.

The evaluation published on Wednesday highlights concerns among prison staff about how they were being expected to carry out assessments of prisoners with little training.

“Some lead assessors perceived that others working with the SRG had a limited understanding of how to use the approach and the principles of risk assessment per se,” it said.

Staff selected to take part in the pilot had received one day of national training or attended a series of briefing events which some assessors had considered too brief for less experienced staff to feel competent delivering a complex assessment, it said.

“It almost feels like on some levels we’re asking people to act beyond their competence and their remit without the full training to safeguard that process,” one prison staff assessor told the evaluators.

'Ethical concerns'

Other staff said they were not adequately trained to make assessments based on discussions with prisoners involving issues to do with Islamic beliefs.

“Given the complex nature of the discussions taking place between the offender and assessor about Islam and the history of Islam, receiving training in philosophical/spiritual influences was identified as an important area to cover by staff,” the evaluation said.

“Here, staff felt that a lack of knowledge in this area could leave them feeling unsettled and de-skilled to conduct a robust risk assessment as they were unable to fully understand what the offender was discussing.”

One prison staff assessor complained: “You’re trying to implement something that you don’t understand as well as having a discussion on a subject that you know nothing about.”

To meet this challenge, some staff were sent to attend a two-day “Islamic awareness” course, the evaluation said. But elsewhere, assessors had “spent their own time researching the area on the internet”.

The evaluation recommended that the awareness course should be incorporated into a fuller training package to ensure a “consistency of training which is vital for ethical and legal defensibility”.

Other prison staff said they had ethical concerns about the potential use of a tool which had primarily been designed with al-Qaeda-influenced prisoners in mind to assess other groups.

One assessor said: “I think there is enough commonality in this sort of behaviour, psychologically, to make sense; it doesn't make sense to me to have one for Muslim extremists and one for animal rights. I think they do share enough of the fanaticism I suppose.”

But the evaluation concluded that such views were “not widely shared” and said that the definition of who to include within the SRG remit should be revisited.

“The pilot said look at a convicted terrorist or extremist, or an affiliate, or someone perceived to have extremist views. Now to me that is really, really dangerous,” another staff member commented.

'Contrasting aims'

Other issues raised included concerns about a clash of cultures between different agencies involved in the assessment work, with the police and probation services having “contrasting aims and objectives”.

“They [the security dept] have their own agenda with these prisoners, and their agenda is more about monitoring and observing… more about controlling it,” one prison staff member said.

But the evaluation said that one positive outcome of the pilot had been greater coordination between prison staff, imams and security services, with information from assessments being shared with police.

“For example, one site described the SRG as providing police with information on an offender’s ideology and the risk this may represent in the broader context of their life,” it said.

“In addition to facilitating external multidisciplinary working, the SRG was also reported to have had a within-site beneficial impact by encouraging closer working and information sharing between psychologists and offender supervisors.”

The evaluation concluded that there was uncertainty in prisons and probation settings about “what exactly the SRG was measuring” and how any findings based on the tool should be used.

It added that the risk assessment tool, renamed the ERG22+, had been “further developed and improved using the findings from the study” since the evaluation took place and “rolled out for use across custody and community sites in England and Wales”.

“Validation work is currently being undertaken on the measure and further research is being carried out on the use of ERG 22+ with TACT [Terrorism Act] offenders,” it said.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.