The uphill struggle of Sahrawis battling Morocco on Western Sahara's berm

Mohamed Bashir, Mohammed Juda and Buda Mohammed Buda all volunteered together in 2020 to join the armed forces of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) and fight at the frontlines of the conflict with Morocco.

The three friends, like thousands of other young men in the Sahrawi refugee camps in southwest Algeria, were enthused about the prospect of restarting the war with the kingdom that has occupied their homeland since 1975.

Growing up as friends and neighbours among the roughly 174,000 Sahrawi refugees who have lived in the camps for almost half a century, each of them had relatives who fought against Morocco in the 1970s and 80s and the stories of their fighting - and often "martyrdom" - inspired the three young men.

Juda, in particular, lost five relatives in the war. His father was wounded in fighting in the 80s, succumbing to his wounds in 2003.

That conflict was paused in 1991 when a ceasefire was brokered with the promise of a referendum on Sahrawi independence. That vote was never held, however, and in 2020 hostilities broke out once again.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

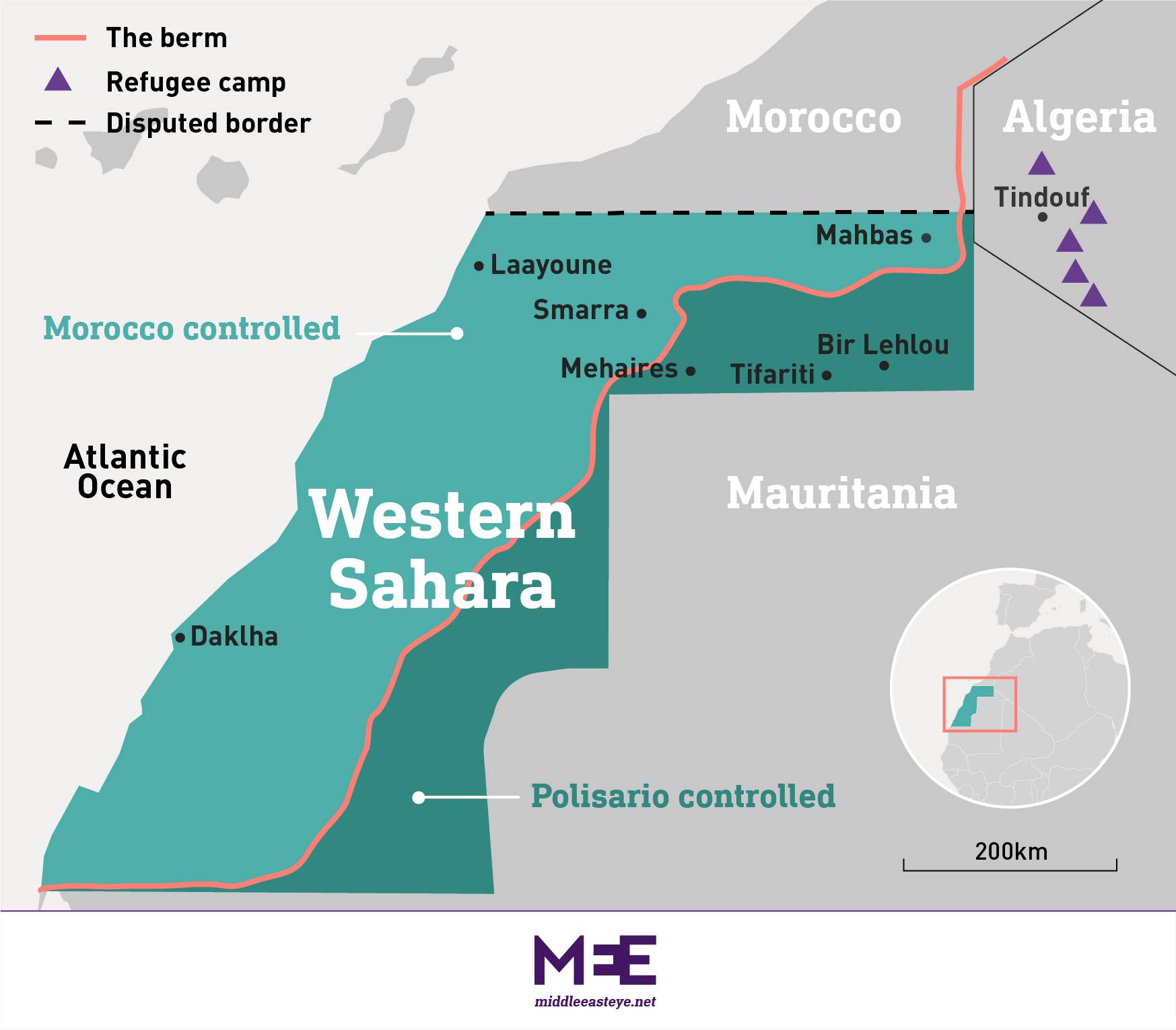

Fighting is found mostly along the berm, a fortified sand wall that runs down Western Sahara, delineating areas held by Morocco and territory nominally controlled by the SADR, the Sahrawi quasi-state that is dominated by the Polisario Front liberation organisation.

When the ceasefire dissolved, Bashir, Juda and Buda all signed up to fight.

"I believe like every Sahrawi... that we have to fight to get our free homeland or we will die like my father, like my uncles, and that's what I believe in," said Juda.

Young Sahrawis like these have boundless drive, fervour and optimism that an independent Western Sahara is possible. Despite this, analysts - and, to an extent, the soldiers themselves - say the fighting has become hopelessly one-sided as a result of the advanced drone technology Morocco uses, which the Sahrawis have little or no way of countering.

'What was taken by force can only be recovered by it'

- Buda Mohammed Buda, Sahrawi fighter

For decades, Sahrawi refugees have pinned their hopes for brighter futures on the eventual return to their homeland, but at the moment that prospect may be further away than ever.

"We believe that it is a chance and opportunity," said Bashir. "Going to war is an opportunity to free our Western Sahara."

Buda was even more unequivocal that the almost 30 years of ceasefire, during which time they waited for the proposed referendum that never materialised, had been a "waste of time".

"What was taken by force can only be recovered by it."

An unbalanced conflict

It's fair to say that the war between Morocco and the Sahrawis is less than evenly matched.

The kingdom can count on the United States, which provides around 90 percent of Morocco's arms, as well as Turkey and France as allies and suppliers. Meanwhile, a 2020 recognition agreement with Israel has seen Morocco gain access to top-of-the-range drone technology.

Speaking to Middle East Eye from Ausserd refugee camp, where they were on leave and helping manage security at the Sahara International Film Festival, the three friends said they would soon return to the fighting despite the odds stacked against them and the losses already sustained.

Though the Polisario does not disclose official figures on military losses, Juda said he had already lost 11 close friends in the fighting, while many more had been wounded.

He spoke of of his own traumatic experience becoming trapped in one of the minefields that litter the area around the berm, which Morocco built to lock Polisario and displaced Sahrawis out of 80 percent of Western Sahara.

Juda had to take perilous steps to escape, checking the ground a foot at a time to avoid being blown sky high.

Both mines and drones have left their mark on large numbers of Sahrawis across the refugee camps. The Landmine Victims' Centre and Sahrawi Mine Action Coordination Office (SMACO) in Rabouni camp document the widespread wounds and fatalities that Moroccan weaponry has left on the refugees.

Those hazards add to an already hard existence for those in the Algerian camps, with little or no running water and limited electricity, scant medical facilities and inhabitants entirely reliant on aid and the hope that their almost 50 years residency is still only temporary.

"We don't belong to here. We belong to our Western Sahara," said Juda.

That enthusiasm is met with a clearly uphill struggle for the Sahrawis.

In December 2020, the Trump adminstration agreed to recognise Morocco's sovereignty over Western Sahara in exchange for the kingdom's recognition of Israel. Despite some grumbling from Democrats at the time, Joe Biden has not reversed this stance.

Sahrawi activists within the Moroccan-held territories face abuse, surveillance and imprisonment. Female campaigners have allegedly been subjected to repeated sexual assaults by Moroccan security forces over their activism.

With few friends outside of longtime patron Algeria, and the world's attention turned elsewhere, Sahrawi fighters have to work with what little they have.

Most of the weaponry they use, said Bashir, were the spoils of war captured from the Moroccans, as well as those supplied by friendly countries - though he declined to name which ones.

"We have our faith. We are not afraid. We are soldiers. We have that anger. We have that. And that's this feeling inside us, coming from a faith that we will have a free Western Sahara. That's what we have," he said.

"They have the drone."

'He left friends behind him, a wife and a family. But at the same time it was just his destiny'

- Mohamed Bashir, fighter

Sahrawi fighters say Morocco's drones have upended the conflict. According to Bashir, in previous years they had been able to counter Moroccan warplanes. Though Polisario still has aging anti-aircraft guns, combatting the new drone technology has proved far more difficult.

"It is our biggest issue because it is killing everyone from the air so they don't [directly] have to fight with us," said Bashir.

According to SMACO, since 2021, 86 civilians, including two children, have been killed in drone strikes, while 170 others have been wounded. Animals belonging to inhabitants of Polisario-held Western Sahara, known by refugees as the liberated territories, have also been killed.

Practically, the options for fighting back are limited for Sahrawis.

According to Federico Borsari at the Center for European Policy Analysis, as of last year Morocco was in possession of 150 vertical take-off and landing drones, including WanderB, ThunderB and the "kamikaze" drone SpyX produced by the Israeli company BlueBird Aero Systems. The kingdom also has three Heron TPs and Harop ammunition produced by Israel Aerospace Industries, as well as four Hermes 900 drones produced by Israel's Elbit Systems.

Morocco also had Turkish Bayraktar TB2 drones and Chinese Wing Loong II drones, both used for combat purposes.

He said when it came to "high-end medium-altitude systems" such as the Bayraktar TB2 drone, there was little the Sahrawis could do, although it would be possible to target lower-flying drones with anti-aircraft weaponry.

"It's also about developing ways and tactics to minimise your physical exposure to drones, conceal your movements and positions, avoid large gatherings that could offer juicy targets, use deception and terrain, etc.," Borsari told MEE.

"In this respect, Polisario can use some of these ideas to improve its resiliency against Moroccan drones."

A number of non-state actors have also developed their own effective drone technology in recent years as it becomes cheaper and more widely available, perhaps most notably Yemen's Houthi movement, who have used drone warfare to disrupt shipping in the Red Sea in solidarity with Palestinians suffering under Israel's war on Gaza.

Asked about whether similar options could exist for a group like the Polisario Front, Borsari said it largely came down to a question of patronage.

"The Houthis' drones are largely if not entirely derivatives of Iranian designs and their production is supported directly by Tehran," he said, noting they are more sophisticated than repurposed consumable commercial off-the-shelf drones seen in Ukraine.

"Furthermore, the Houthis have developed significant experience in using drones, in terms of trained personnel and concept of operations. This process doesn't happen overnight. Overall, the Polisario can hope to develop similar capabilities only with Algeria's support."

'This is a destiny'

The future for young people in the refugee camps is very limited.

While some can travel to other parts of Algeria, or even Spain and Cuba for higher education, the prospects of further employment are weak.

In that context, it is hardly surprising that the fight for a return to the homeland - one many have never been to - can seem like the only option available.

"This is a destiny. This is what we have to face. We knew that," said Bashir.

"The hardest thing is when a friend you know dies there and becomes a martyr... and you are sad, but at the same time, because he's a martyr you are happy for him because his destiny is just to go to heaven," he added.

"But at the same time he died. He left friends behind him, a wife and a family. But it was just his destiny."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.