Financial aid: How dependency on donors leaves Palestinians trapped

Since he was sworn in as the president of the United States only two years ago, Donald Trump has dangled economic promises to the Palestinians as an incentive to make concessions in his so-called "deal of the century" peace plan.

At the same time, however, the US administration has employed financial cuts to long-standing programmes - including the agency in charge of Palestinian refugees, UNRWA - as punishment against Palestinian leaders for refusing to accept Israeli and US terms for talks.

Done deal: How the peace process sold out the Palestinians

+ Show - HideMiddle East Eye's "Done Deal" series examines how many of the elements of US President Donald Trump's so-called "deal of the century" reflect a reality that already exists on the ground.

It looks at how Palestinian territory has already been effectively annexed, why refugees have no realistic prospect of ever returning to their homeland, how the Old City of Jerusalem is under Israeli rule, how financial threats and incentives are used to undermine Palestinian opposition to the status quo, and how Gaza is kept under a state of permanent siege.

-

Annexation: How Israel already controls more than half of the West Bank

-

Refugees: How Trump’s ‘deal of the century’ is doomed to failure

-

Jerusalem's Old City: How Palestine's past is being slowly erased

-

Gaza: How the Palestinian enclave has been strangled

-

Financial aid: How dependency on donors leaves Palestinians trapped

But while Trump's slashing of funds for the Palestinian Authority (PA), UNRWA, and humanitarian projects benefitting civilians may appear particularly extreme, the Palestinian economy has long been held hostage in a bid to coerce the Palestinian leadership into returning to the negotiating table with Israel.

Aid dependency

The Palestinian economy is intrinsically linked to international support, particularly so since the establishment of the PA in 1993 as part of the Oslo Accords.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

An estimated $2bn was initially pledged to the PA by foreign donors in 1993 in order to build the governmental institutions that would eventually be incorporated into a future state of Palestine - had the terms of the Oslo Accords been followed, that is.

Since then, the PA has depended on foreign support to help pay its 137,000 employees, run its ministries, and ensure water, electricity, sewage and medical treatment access in Palestinian towns and villages.

In 2003, foreign aid to the PA amounted to 58 percent of its budget, worth $747m according to the Palestinian Ministry of Finance. As the PA grew, and in doing so began to depend more on taxation, the proportion of the budget coming from foreign aid slowly decreased - making up only 15.4 percent of the 2016 budget - roughly $733m.

Nonetheless, this aid has not been without strings attached.

The current American administration has drastically reduced its contributions to organisations benefitting Palestinians in the past two years, applying financial pressure in the hope of obtaining political compromises on key issues such as the fate of East Jerusalem, refugees' right of return, and the status of illegal Israeli settlements in the West Bank.

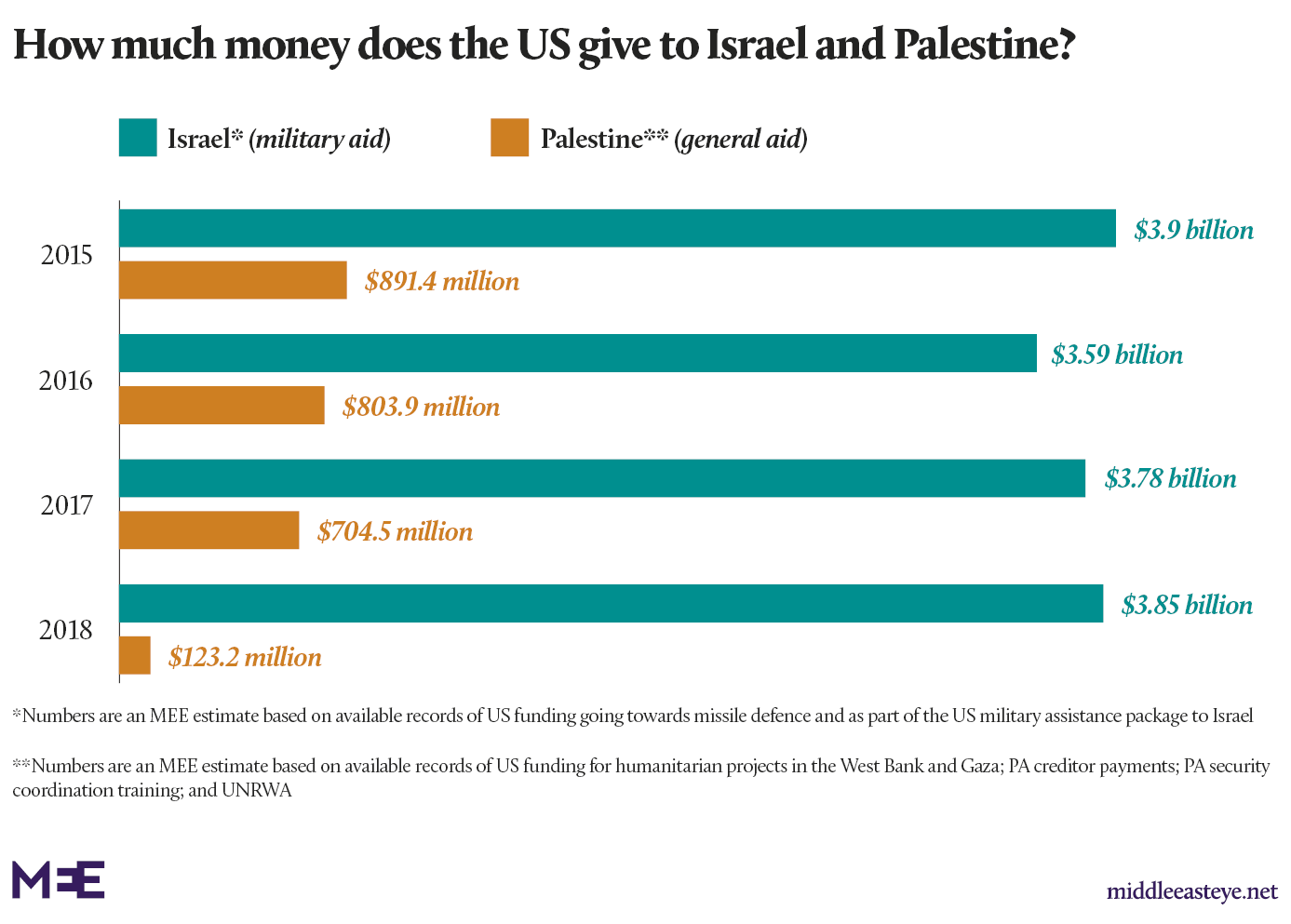

In contrast to its ever-shrinking financial aid to Palestinians - while overall foreign donor funding decreased by a third between 2008 and 2018 - the US continues to provide Israel with billions of dollars in military aid each year.

Taxes held hostage

While the PA has relied more and more on taxes to fund its budget, what should be a straightforward matter of state finances has been anything but.

The PA directly collects domestic taxes from its citizens, amounting to $764m in 2017 out of a total domestic revenue of $1.15bn.

But under the Paris Protocol signed in 1994 as part of the Oslo Accords, Israel collects taxes on Palestinian imports and exports as well as VAT on behalf of the PA.

In 2017, customs revenue transferred by Israel to the PA - also known as clearance revenues - amounted to $2.49bn.

On average, Israel collects around $175m each month in taxes on Palestinian imports and exports on behalf of the PA.

Like the rest of the Oslo agreements, what was intended to be a temporary arrangement pending the creation of a fully fledged Palestinian state remains until this day, shackling the Palestinian economy to a stalled peace process, US pressure and years of occupation that restrict the movement of goods and people, vital elements for any economy to grow.

Moreover, Israel has yielded the Paris Protocol as a punitive tool against Palestinians, using the customs fees and taxes it collects on behalf of the PA as a means of pressure on the Ramallah-based government.

The most recent case was in February, when Israel withheld $138m in tax transfers to the PA as retaliation over payments made by Palestinian institutions to Palestinian prisoners held by Israel, as well as to the families of Palestinians killed by Israelis.

While PA President Mahmoud Abbas has said that the PA would refuse any incomplete transfers of funds from Israel, the latest dispute has put the PA further at risk of diving into an intractable financial crisis.

Facing a financial abyss

Between 2012 and 2016, the four biggest donors to the Palestinian Authority were the EU and its individual member states ($981m), Saudi Arabia ($908m), the World Bank ($872m) and the US ($477m), according to PA Ministry of Finance reports.

The situation has dramatically changed since the US severed all funding to UNRWA in 2018, despite having been its leading financial contributor since the agency's inception.

Meanwhile, state agency USAID ceased all its foreign aid payments to the PA in February.

The agency had spent $268m on public projects in the West Bank and Gaza as well as Palestinian private sector debt repayment in 2017, but significant cuts to all new funding were already in place by June 2018.

The USAID cuts, however, have been at the request of PA officials fearful of being sued in the US under the 2018 Anti-Terrorism Clarification Act (ATCA), which entitle American citizens to take recipients of US money to court for alleged "acts of war".

The cuts have nonetheless left the UN and Palestinian leadership scrambling to find alternative sources of funding.

With the US almost completely out of the picture, the EU is by far the largest donor of the PA. In 2018, it paid $171m in assistance to the PA and $415m in total aid benefitting Palestinians.

Traditionally, the Saudi kingdom has also been a generous donor to the Palestinian Liberation Organisation, the umbrella Palestinian political body, but it also gives the PA around $220m annually.

After Israel withheld taxes collected on behalf of the PA earlier this year, Qatar - which usually contributes financially to Gaza-centred aid - pledged $480m to rescue the PA from collapse.

The PA has rarely been so strapped and desperate for cash since its foundation in 1993.

Gaza on the brink of ruin

While the Fatah-led PA based in the occupied West Bank has been struggling, the Gaza Strip has been in even more dire straits.

Under an air, sea and land siege imposed by Israel and Egypt since Hamas took over control of the small coastal enclave after a power dispute with Fatah in 2007, the Gazan economy has been heavily dependent on international aid to subsidise its education, medical and humanitarian services.

In 2014, various UN organisations sent a total of $845m in aid to the Gaza Strip, the same year the Palestinian territory suffered under a devastating war with Israel. The damage caused by the war was such that the PA estimated it would cost $7.8bn to rebuild in the aftermath of the seven-week conflict.

Despite the continued feud between Hamas and the PA, Gaza remains reliant on PA funds, which accounts for one third of its budget. In 2016, the PA allocated nearly $1.5bn to Gaza, despite as little as $325m in revenue from taxes and customs being collected in the Strip.

But the rift between Fatah and Hamas has also meant that, just as the PA has fallen under Israeli and US pressure, it has used money to coerce Hamas into political compromise.

Most PA funds in Gaza go to its employees there. While the vast majority do not work, due to the PA's insistence that they not contribute to the Hamas-led authorities, their salaries are a vital security net for many families as more than half of Gaza residents live in poverty.

In the past two years, however, the PA has repeatedly slashed these salaries as a way to punish Hamas, leaving thousands of civilians worried about their survival as US cuts to UNRWA have also affected the livelihoods of countless others.

Pennies for Palestine, largesse for Israel

Palestinians' recent financial woes under the Trump administration stand in stark contrast with the US's continued generosity towards Israel.

In 2018, the PA's total budget stood at around $5bn. That same year, the US gave Israel $3.85bn in military aid alone.

While much of the foreign aid to the occupied Palestinian territories has gone to paving roads and providing basic services, the US has simultaneously heavily invested in Israel's military capacities, which play an essential part in maintaining the occupation of Palestinian lands.

In fact, one could argue that continued American support of Israel's military directly impedes the effectiveness of foreign aid to Palestinians.

Cases abound of foreign-funded infrastructure, including hospitals and schools, being destroyed during military offensives or in the course of routine army activity in the West Bank.

The self-defeating cycle is so pervasive that Palestinians have a saying that goes: "The EU fund, the PA builds and Israel destroys."

Meanwhile, with reports emerging that the Trump administration has been seeking large donations from Arab Gulf countries, the US, EU, Japan and China to fund the economic component of the peace plan, one high-income country remains conspicuously unsolicited for funds despite being in the eye of the storm - Israel.

Economic chimaeras

The US-led "Peace to Prosperity" workshop in Bahrain on 25 June, meant as the opening salvo before the rest of the "deal of the century" is revealed, highlights how pivotal economic pledges are in the US's plan to achieve peace.

But what Trump's advisor on Israel, Jason Greenblatt, has hailed as the "opportunity of a generation" has preemptively been dismissed by Palestinian leadership as an attempt to "trade [...] political rights for money".

This is not the first time Palestinians have been presented with enthusiastic pitches for economic opportunity that later fizzled into nothing. A "Gaza and Jericho first" plan; industrial zones; a deep-water port built on an artificial island; a short-lived airport; all these projects meant to breathe life into the Palestinian economy either failed to ever see the light of day or never delivered on their promises.

While Trump's son-in-law and adviser, Jared Kushner, who has been charged with putting the "deal of the century" together, seems to believe that "only" an environment conducive to business investments can grant Palestinians "self-determination and better lives," many Palestinians see financial promises as fundamentally meaningless so long as Palestinians do not have a sustainable sovereign state to enact and benefit from such economic measures.

One thing seems certain: without addressing the root causes of the Palestinian economy's instability, the deal of the century's heavy dependence on financial incentives to get Palestinians to acquiesce to a peace deal appears doomed to maintain the status quo.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.