War on Gaza: Palestinians escape Rafah to 'miserable life' elsewhere

On almost every street in western Khan Younis and Deir al-Balah, dozens of cars, trucks and animal-drawn carts are seen laden with luggage, mattresses and blankets.

They carry Palestinians fleeing Rafah, where Israel has expanded its aerial bombardment and ground attacks in recent weeks.

"We stayed in Rafah for around four miserable months with very little aid and no running water," said Ahmed Abu al-Enein, 39, who was originally displaced from Jabalia, in the northern Gaza Strip.

"But we had no other choice, either a miserable life or death."

Abu al-Enein is now on his fifth displacement, carrying his tent once again to Deir al-Balah, where he set up camp with his family near the seashore.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

He is one of nearly 900,000 people who have been forced out of Rafah since early May due to a fresh Israeli ground assault there.

Rafah, the southernmost city in the Gaza Strip, had become a shelter for the internally displaced after Israel pushed them out of other parts of Gaza earlier in its ongoing military campaign, which has killed over 35,000 people and wounded 80,000 more.

For months, the small city bordering Egypt was turned into a large makeshift camp, with tents scattered all around.

'Today in Deir al-Balah, we face both a miserable life and the looming spectre of death'

- Ahmed Abu al-Enein, internally displaced Palestinian

Most UN and international organisations moved their bases to Rafah too and had their aid warehouses in the city.

Though it was still subject to repeated deadly air strikes and aid restrictions and struggled to accommodate the growing numbers of displaced people, the border city had become the best available option for people's survival.

But western Khan Younis and Deir al-Balah, to where Israel is now forcing Rafah’s displaced to move, have significantly weaker infrastructure, limited space and fewer service capabilities.

"We fled Rafah under intense Israeli bombardment and came here thinking it would be safer," Abu al-Enein told Middle East Eye.

"But we not only found similar conditions in terms of the relentless bombardment, but even worse conditions in terms of residence and infrastructure," he said.

"Today in Deir al-Balah, we face both a miserable life and the looming spectre of death."

'What am I supposed to do if we get injured?'

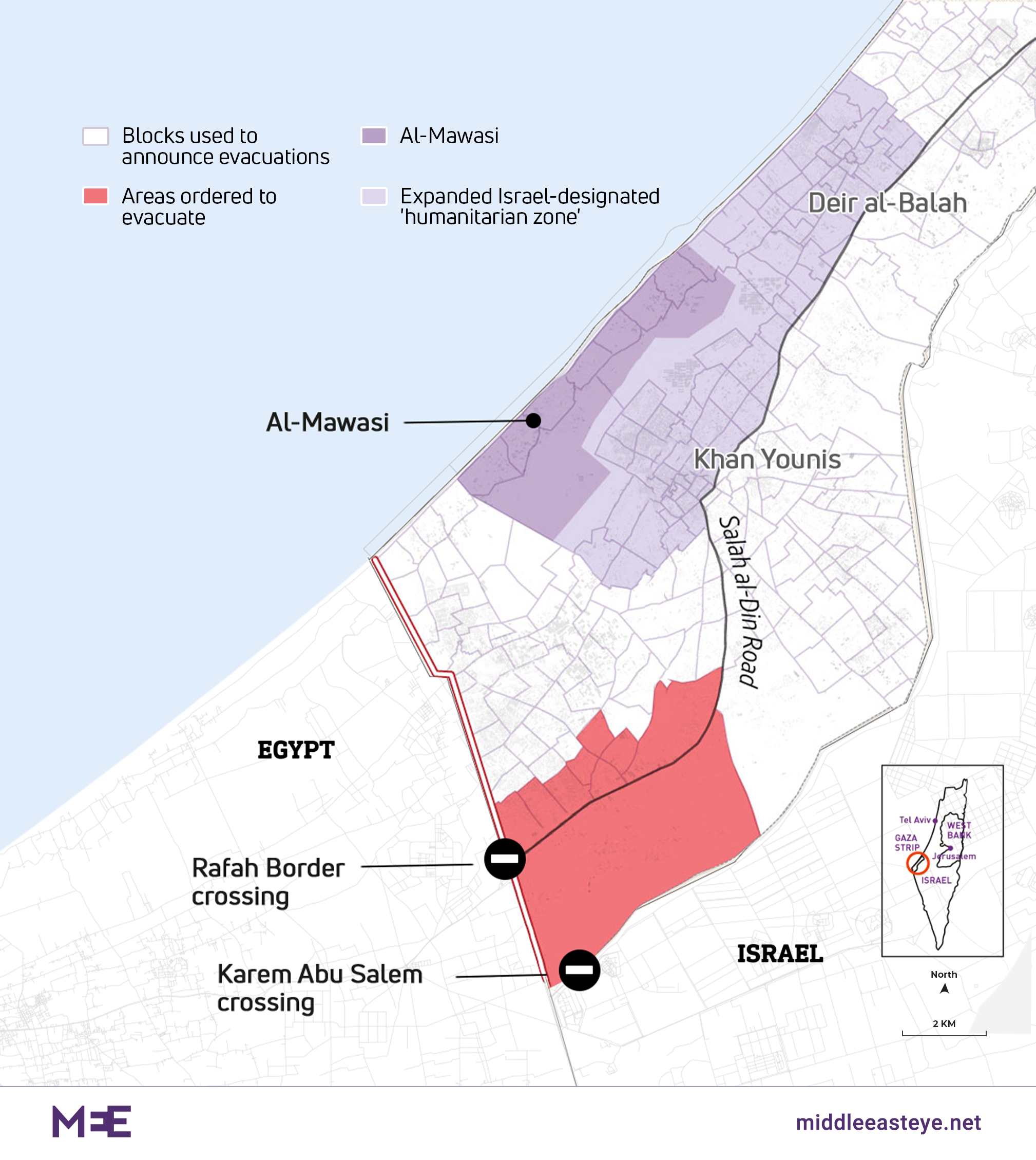

Most people fleeing Rafah are arriving in Deir al-Balah and western Khan Younis because those areas have been designated as "humanitarian zones" by the Israeli military.

Even though Israeli forces have shelled and killed Palestinian civilians inside such zones in previous months, many say they have no other option as the army blocks them from returning to their homes in northern Gaza.

Deir al-Balah, a small city with an area of 14 sqkm, was home to an estimated 80,000 people before Israel's ongoing war.

It is now receiving a daily influx of displaced Palestinians but has the only main public hospital available in the whole of the central Gaza Strip, the al-Aqsa Martyrs hospital.

Overwhelmed with victims of Israeli strikes and the growing number of patients due to unhealthy living conditions, the hospital is struggling to continue operating.

An Israeli seizure of the Rafah border crossing earlier this month has blocked the entry of lifesaving medical aid and fuel.

On Friday, the UN's humanitarian agency Unicef said oxygen generators were set to shut down due to the fuel shortages, risking the lives of more than 20 newborns.

Abu al-Enein said his eldest daughter, aged 17, has been suffering from severe abdominal pain and diarrhoea for a week but had avoided going to the hospital knowing doctors could not help them.

But as the pain became more unbearable, he was forced to take her to al-Aqsa Martyrs hospital.

"They did a few insufficient tests and said that she, like hundreds of others arriving every day, has hepatitis," he said.

"They didn't give her any medicine. They just advised her to take some rest and eat sweets. That's it.

"Now what am I supposed to do if we get injured? After I saw the hospital's condition, I prayed to God that if we get targeted, we would immediately die so that we would not suffer and die slowly due to the lack of treatment."

Since the start of 2024, a hepatitis epidemic has emerged in the Gaza Strip, exacerbated by overcrowding in displacement centres and the absence of adequate living conditions, including clean water and hygiene products.

Health officials have also noticed outbreaks of diarrhoea and skin illnesses among the population.

According to the World Health Organisation, between mid-October and 2 April, at least 643,254 cases of acute respiratory infections were recorded in the Gaza Strip, along with 345,768 cases of diarrhoea (including 105,635 among children under five), 83,450 cases of scabies and lice, 47,949 cases of skin rashes, and 7,293 cases of chickenpox.

In western Khan Younis, the situation is equally dire. The biggest hospital there, the Nasser Medical Complex, was the largest hospital still operating in Gaza following Israel's destruction of the strip's main hospital, the al-Shifa medical complex.

But during the three-month Israeli invasion of Khan Younis, the hospital was attacked, raided and besieged, putting it out of service.

After Israeli troops pulled out from the city in April, three mass graves containing hundreds of bodies were found there, which Palestinians say were dug by the army.

Last week, Doctors Without Borders announced it had resumed some of its operations at the hospital, "with outpatient and inpatient departments focusing on orthopaedic surgery, care for burns, and occupational therapy services".

The organisation said maternity services would also be operational in the coming days.

A 20-minute drive east of Nasser hospital lies the Gaza-European hospital, which was operational until recently.

However, medical officials said last week the hospital had ceased operations due to a fuel shortage, putting the lives of hundreds of patients and wounded people at risk.

Returning to Rafah

Since the Israeli troops began advancing into eastern Rafah on 6 May, they have pushed deeper into the city each day, targeting central and southern areas.

More people have been told by the military to head to the "humanitarian zone", but the infrastructure there is already collapsing.

Sewers have overflowed into the streets, and garbage has spread throughout neighbourhoods and displacement centres, worsening an already existing health and environmental crisis.

In the Mawasi area in Khan Yunis, Mustafa al-Banna's family is preparing to return to their shelter in Rafah after they failed to find a makeshift tent to accommodate them.

'They either risk returning to Rafah, where there is bombardment ... or stay in Mawasi where there are no life essentials'

- Mustafa al-Banna, Palestinian

Banna, who along with his pregnant wife fled Gaza to Egypt in March, is still managing his elderly parents' affairs from afar, desperately searching for a safe and suitable shelter for them.

"They could not find a tent there, so my father, mother and brother stayed in the tent with my sister and her husband and their four children," the 30-year-old journalist told MEE.

"Nine people were staying in one tent, with no infrastructure, no water, no services and no health facilities."

Mawasi is a narrow coastal strip west of Khan Younis, comprising approximately three percent of the Gaza Strip's total area of 365 sqkm.

Being a relatively empty area before the Israeli war, Mawasi, about 28km south of Gaza City, contained only around 100 housing units. It has no schools, hospitals or other essential facilities.

A few days after arriving there, Banna contacted the owners of the room they rented in Rafah to see if it was still available for his family to return.

"These conditions made us think of returning them to Rafah again, which for sure is a dangerous decision, but the situation has been harsh in all cases anyway and the choice is hard," he said.

"They either risk returning to Rafah, where there is bombardment and killing, or stay in Mawasi where there are no life essentials."

Banna, who is originally a resident of the Sahaba neighbourhood in the east of Gaza City, expressed his distress at witnessing the struggle of his elderly parents "after all these years to obtain the basic life necessities".

"They will return to Rafah," he said. "And whatever happens, happens."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.