War, riots, torture: Which luxury hotels shaped the Middle East?

The management of Riyadh's Ritz-Carlton would probably like the hotel to be known for its "lavishly landscaped gardens, spacious and sumptuous accommodations, fine-dining restaurants," and, of course, its gentlemen-only spa.

Yet today, and almost certainly for some time to come, these luxury trimmings are unlikely to be the first thing to come to mind for any passers-by on the Mecca Road.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The Ritz-Carlton secured itself a place in Middle East legend when the Saudi government detained some 200 members of the country's elite there in early November, turning the building into a sprawling gilded prison in what appears to be the greatest shakedown in history.

A spokesperson for Marriott International, which runs the hotel, told Middle East Eye that the hotel was not operating as a traditional hotel for the time being. "We continue to work with the local authorities on this matter."

Certain luxury establishments have become synonymous with dynamic eras in the region's history

The hotel finds itself in good company. Across the Middle East, certain luxury establishments have become synonymous with dynamic eras in the region's history, as well as being identified with famous, infamous and influential figures.

Often - as with the Riyadh Ritz-Carlton, where reports of torture have emerged - these hotels are swept up in moments of crisis, brutality and bitter violence.

And although apparent images of the Ritz-Carlton's dining room transformed into a dormitory for Saudi security guards are fascinating, such scenes are not as uncommon as one might think.

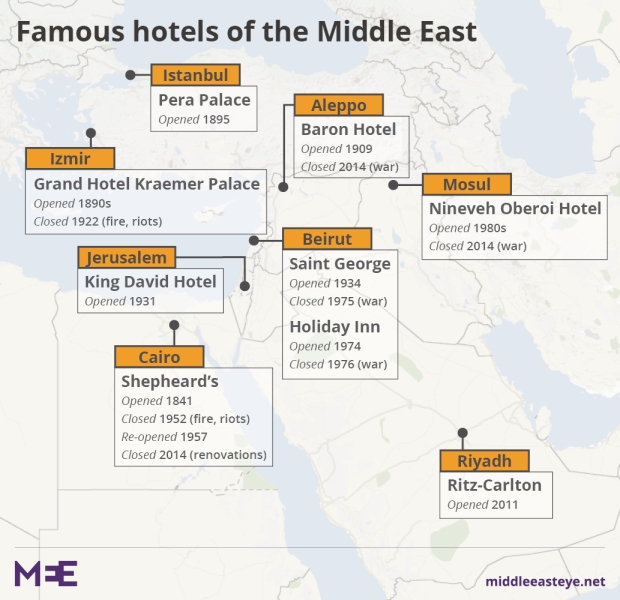

From Jerusalem to Istanbul, Beirut to Aleppo, suites, ballrooms and bars have always served as the theatres in which Middle Eastern history is played out.

1. Istanbul: Where east meets west

The oldest establishments, such as Istanbul's Pera Palace, Aleppo's Baron and Cairo's Shepheard's, emerged a century or more ago to cater for the increasing numbers of wealthy Westerners eager to visit the cities and sights of the Near East.

The Pera Palace, built in 1892 to receive weary passengers disembarking from the Orient Express, still bears the coat of arms of the company which once ran the railway that opened up the Ottoman East to Europeans.

This meeting of East and West is visible in the very stones of the building, designed by French-Turkish architect Alexander Vallaury in a mesh of oriental and neo-classical styles.

The hotel, which boasted the first electricity and elevator in Istanbul – then known as Constantinople – immediately became a symbol of modernity.

As a space where foreigners could socialise with Middle Easterners, the Pera Palace was also an early symptom of globalisation, all part of a process that would bring the West closer and closer into the affairs of the East.

"Sultan Abdul Hamid allowed a few Turks to meet foreigners in the hotel, and there were dances and things like that," historian Philip Mansel, author of Levant: Splendour and Catastrophe on the Mediterranean, told Middle East Eye.

It was here, at these new hotels, he said, that Middle Easterners and foreigners could come face to face and socialise.

2. Aleppo: Home to a new, violent history

In Aleppo, once a 1,200km train journey from Istanbul on the Taurus Express, the Baron Hotel hosted glamorous guests, while being an integral part of the city and the country's political scene.

Among the relics and curiosities preserved by the hotel, the oldest in Syria, is the apparently unpaid bill of TE Lawrence – yet another promise broken by the British agent. In 1958, the then-president of Egypt, Gamal Abdel Nasser, chose the Baron's balcony from where to address the people of Aleppo.

"It wasn't just a modern hotel for foreigners, it was part of the political life of the city, and the balcony was full of people for the entry of the emir Faisal in 1918," Mansel said, referring to the future king of Syria and Iraq's conquest of the city during the Great Arab Revolt.

"It was part of the general Syrian political life, because it was modern and central, dynamic and international, as Aleppo had once been."

"Modern" is not a word best suited to today's Baron, which was founded in 1909 and has subsequently changed little.

Since its glory years, travellers to the northern Syrian city have increasingly treated the hotel as a museum piece and time capsule. It became a place to gawp at the tattered leftovers of a bygone era rather than somewhere to spend the night.

But since 2012, when the Syrian war enveloped Aleppo, the Baron has taken on a new, violent history.

Its roof and upper floor are scarred with shrapnel holes. Rooms that once hosted the likes of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk and the writer Agatha Christie have at times become temporary homes for Syrians displaced by fighting and bombardment in the city's east.

3. Beirut: Glamour descends into disaster

In central Beirut lie two more hotels that tell a story of glamour and conflict: the boxy, dusky-pink Saint George, which lies on the coast; and the towering, foreboding Holiday Inn.

Sune Haugbolle, sociologist and author of War and Memory in Lebanon, told Middle East Eye: "Pre-civil war Lebanon was this entrepot between East and West and very modernised, and this was symbolised by these hotels."

Ask older locals what happened in the Saint George during the 1960s and 1970s and you're likely to prompt talk of international superstars including Brigitte Bardot and Peter O'Toole, not to mention more infamous figures such as British spy Kim Philby, who was known to sink cocktail after cocktail in its bar before his defection to the Soviet Union in 1963.

Meanwhile, a few yards up a hill, the Le Corbusier-inspired Holiday Inn stood as an imposing example of Beirut's modernity when it opened in 1974.

The establishment's halcyon days didn't last long. Civil war broke out in 1975 and the neighbourhood became a front line in what would come to be known as the Battle of the Hotels.

The Holiday Inn witnessed some of the most brutal fighting of the early days of the conflict. Its sheer size meant whole floors could be ablaze while the lobby's chandeliers were left untouched and elevators rose and fell still playing their placid muzak.

This scene of refinement disintegrating into chaos came to a head in 1976, when the Palestinians and leftists took control of the hotel and threw Christian militiamen from the windows of the top floor's revolving restaurant, an image that has lived long in Beirut's popular imagination.

"It was dramatic how places where movie stars used to go and stay would be the scene of some of the worst violence of the civil war," Haugbolle said. "You have luxury turned into brutal violence."

The war came to a close in 1990, but the shells of the Saint George and the Holiday Inn still stand untouched.

Although they survive as a result of legal wranglings rather than collective will, the pair now serve as unofficial monuments to the civil war and the aspirational era that preceded it.

Pockmarked with holes gouged out by shelling, and rising out of central Beirut like a great grey tombstone, the Holiday Inn in particular catches the eye.

"It's become a familiar sight, familiar like Big Ben in London," said Gregory Buchakjian, a Lebanese art historian and photographer whose work has often centred on his country's abandoned wartime ruins.

"I remember the first time in my life I saw it. I was five years old. I was in the car with my parents and we passed the Holiday Inn and I saw this thing that was so huge and completely devastated. It was an image I cannot remove from my memory."

Cairo: Target for anti-British riots

Cosmopolitan and playgrounds of the elite, luxury hotels in the Middle East are often some of the first buildings to succumb to social uprisings and conflicts.

"Of course they're targets," said Mansel, "because in cities which are modernising and being changed and have several civilisations inside, the great dynamic modern hotel is particularly prominent and symbolic."

Cairo's Shepheard's Hotel, an ornate example of Victoriana founded as a caravan tavern in 1841, was once the go-to destination in the Egyptian capital.

As Time magazine put it in 1942: "The well-to-do British officers in Egypt, the ambassadors with letters plenipotentiary, the Americans with fat purses, the glamour girls of the Middle East, the Russian commissars, the famous war correspondents and the civilian tank experts, all stay at just one hotel in Cairo: Shepheard's."

When anti-British rioters set Cairo ablaze in 1952, the hotel was one of the arsonists' first targets and disappeared from the city's skyline.

The Shepheard's did reopen in 1957, but situated half-a-mile away from its original home and lacking the age and character of the original, the hotel lost much of its lustre. Its website says it has been shuttered for "renovations" since 2014.

In Izmir, historically known by its Greek name Smyrna, the Grand Hotel Kraemer Palace served as an example of the Anatolian port city's striking cosmopolitanism.

When Ataturk captured the city from the Greeks in 1922, the Turkish leader marched into the Kraemer Palace and asked a waiter of his Greek rival: "Did King Constantine come here to drink a glass of raki?"

"No," came the reply.

"In that case why did he bother to take Izmir?"

But the Kraemer Palace's raki wasn't enough to save it. Soon after, a deliberate fire was ignited, most likely by Ataturk's victorious army, in the city's Greek and Armenian neighbourhoods. Smyrna's ancient multiculturalism, the Kraemer Palace and tens of thousands of lives were lost forever in the blaze.

Mosul: When Islamic State came

In Iraq's Mosul, a wreck of a city recently wrested from Islamic State (IS) control, can be found a more recent example of a luxury hotel caught up in seismic events.

The Nineveh Oberoi Hotel, a 262-room, five-star resort overlooking the Tigris River, had been the number-one destination for visiting dignitaries since the 1980s.

Boasting a pool, bar and Ferris wheel, the Nineveh was a favourite of top government officials and businessmen during Saddam Hussein's reign.

Pleasantries ground to a sudden halt in 2014, however, when Islamic State (IS) swept into Iraq's second city, appropriating much of Mosul's civic apparatus as part of the group’s attempt at building a new Islamic caliphate.

For the victorious jihadists, the capture of the Nineveh represented a special kind of a coup. Fanar Haddad, a Middle East analyst, told MEE: "The Oberoi is, of course, an international brand, one of the best in the world, and it was considered to be the best hotel in town. The ISIS propaganda machine made quite a bit of the capture."

After its appropriation, IS got to work. Decorative stonework was dismantled, IS's black flag was raised on every flagpole, and IS-linked Twitter accounts publicised the hotel's "grand reopening".

While the event did go ahead, normal service was not resumed. As the Iraqi military closed in, so the Nineveh became a snipers' nest and battlefront.

"In terms of PR, it certainly was a big scoop to be able to claim that they had taken this over, and now there's this fancy hotel with ISIS flags fluttering outside of it, regardless of what happens afterwards," Haddad said.

"I think it was more [about] the visuals. For quite a bit of the caliphate there was a virtual side to it that was perhaps more important than the actual physical side, and was certainly glitzier."

The Nineveh Oberoi's future is unclear. The Oberoi Hotels and Resorts group did not respond to questions from MEE about what it plans for the hotel now that the Iraqi army has retaken Mosul.

Certainly, in a city with a catastrophic scale of destruction, the renovation and rehabilitation of a five-star hotel is surely bottom of the list of priorities.

It is not inconceivable, however, that at some time the hotel could reopen and be reconciled with its chilling past.

Jerusalem: 'We don't hide the bombing'

In Jerusalem, the King David Hotel lies on the border between the city's east and west.

Here, in 1946 when Palestine was under British control, the Irgun Zionist group bombed the southern wing, which was being used as military headquarters by the colonial power.

Ninety-one people lost their lives, including Britons, Jews and Arabs, ratcheting up tensions between the three communities and leaving the hotel's wing a devastated chasm.

Despite its deadly past the establishment lives on, still offering the finest service and playing host to celebrities and heads of state.

"We don't hide [the bombing], that's for sure," said Jeremy Sheldon, guest relations manager at the King David. "There are photos of it, we have a historical wall on the lower lobby level of the hotel, we also have historical pictures throughout the hotel. But it's not something that we particularly go out of our way to talk about either."

Today the southern wing is rebuilt and fully functioning, with six floors of rooms. The bombing has merged into the greater story of a hotel that has witnessed Jerusalem's anxious history play out since 1931. "A lot of people really do enjoy the history and that's one of the reasons they come here," Sheldon said.

Perhaps one day the management at the Riyadh Ritz-Carlton might say the same.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.