Western Sahara still waiting as peace talks 'in danger of becoming a show'

Mansour Mohamed Moloud’s life revolves around reading and activism. This week, after breakfast, the 26-year-old has been reading William Shakespeare’s Hamlet in English.

In the evening he meets with friends in a secret location to review and edit video footage and photographs captured that day.

Armed police try to stop a demonstration to mark the anniversary of an activist who allegedly died at their hands. The arrest of a media activist. Women dressed in bright abayas prevented from raising a banned flag.

These are not scenes from a modern day Shakespearean tragedy, but the reality of life in what is dubbed "Africa’s last colony" – Moroccan-occupied Western Sahara.

Speaking from Laayoune, its capital, Mansour tells Middle East Eye: “We are harassed for speaking our minds but we don’t want to be silenced. Morocco is silencing everyone who tries to share their story.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Competing claims over the territory Morocco refers to as its “southern provinces” stretch back decades. The indigenous Sahrawi population's long-standing dream of self-determination has led to outright war, grave human rights abuses and the curtailment of freedoms.

And while talks aimed at resolving the conflict have been taking place in Geneva in recent months, a diplomatic source has told MEE that a behind-the-scenes intervention from the Americans may put an end to hopes of Sahrawi independence.

Moreover, political turmoil in neighbouring Algeria could also have major impact on any political settlement, the source said.

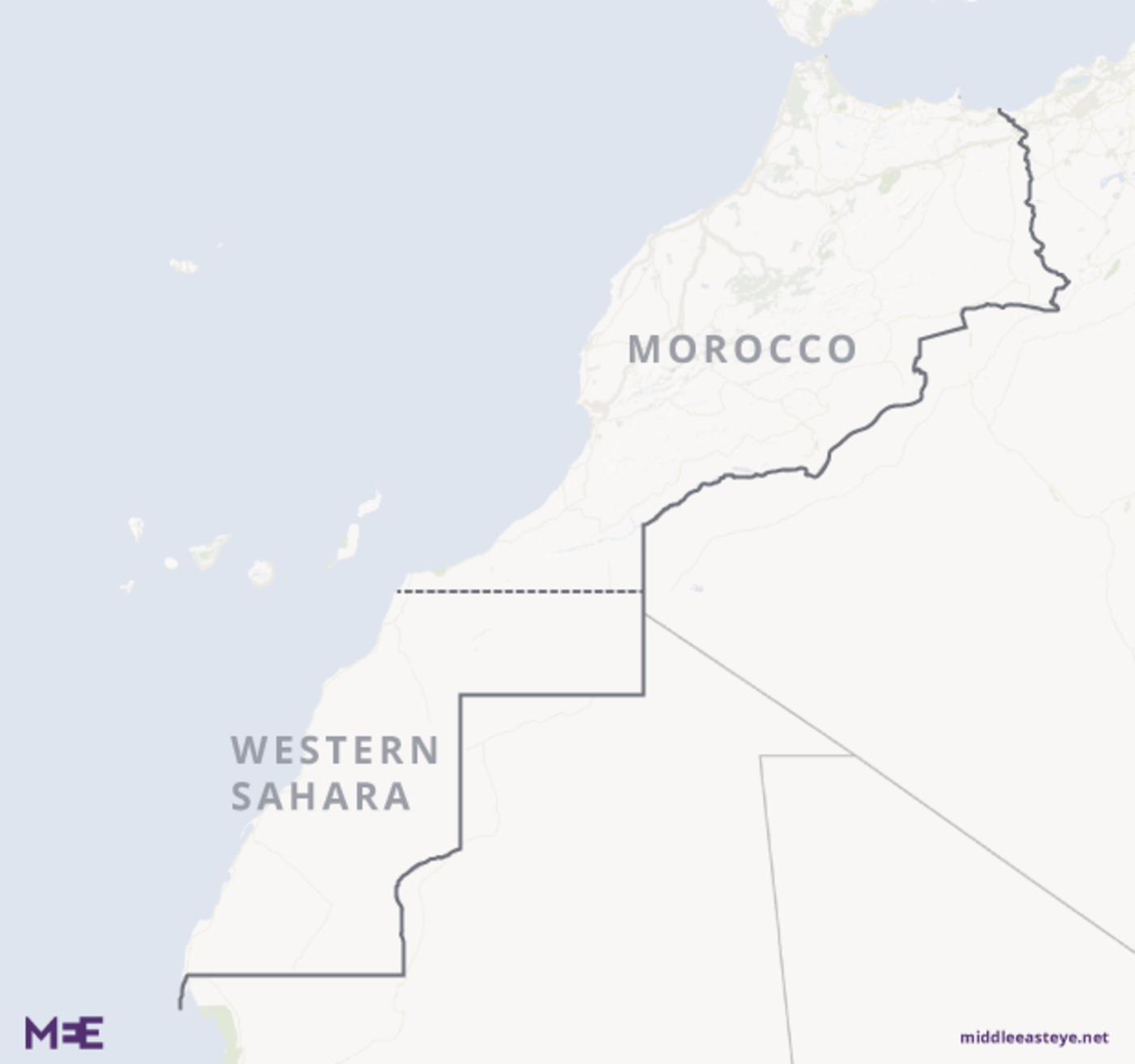

The desert territory sits on the western shoulder of Africa, north of Mauritania and south of Morocco. Approximately the same size at the United Kingdom, its inhospitable climate makes it one of most sparsely populated places on earth.

Nevertheless, waters off its Atlantic coast teem with fish and vast phosphate deposits lie deep beneath its sands.

Morocco has occupied most of the territory since 1975, the same year that colonial Spain pulled out, and has sought to tap and trade these resources, a process which has been deemed illegal by Sahrawis.

The invasion was followed by a 15-year guerrilla war between Morocco and the Algeria-backed Polisario Front, a liberation movement that represents the Sahrawi people, which ended in 1991 when the Sahrawis were promised a vote on self-determination.

That vote has never materialised, despite the presence of a UN force since 1991 whose mandate is to prepare the territory for a referendum on self-determination.

This week, UN Secretary General Antonio Gutteres said that “a solution to the conflict is possible”, in comments included in a report on two rounds of negotiations that have brought together Morocco, the Polisario Front, Algeria and Mauritania, and which have been hosted in Geneva by Horst Koehler, a former president of Germany.

Gutteres added that a settlement would require a “strong political will, not just from the parties and neighbouring states, but also from the international community”, according to the report seen by AFP.

At the same time, Middle East Eye understands that talks between Koehler, Morocco and the United States are taking place in Washington, with the possibility that Polisario and the Sahrawis will once more be sidelined as they seek a referendum.

Same old, same old

Asked if he thought the talks could lead to a solution to the decades’ old conflict, Mansour said “I don’t think so.”

He accused Morocco of entering negotiations “without good faith” because of their insistence on a proposal to end the conflict which falls far short of a referendum on independence.

The kingdom's Western Sahara Autonomy Plan would grant Western Sahara limited self-government under the sovereignty of Morocco, which would control defence and foreign affairs.

But Mansour, in line with the position of the Polisario Front, will settle at nothing less than a referendum on self-determination.

“A solution without voting is not logical,” Mansour said. “We have to vote. It’s about self determination.”

Samir Bennis, political analyst and editor-in-chief of Morocco World News, said while the talks were a “good step in the right direction”, the only viable solution was the autonomy plan.

“Morocco has stated its position more that once. It is clear that anything that is beyond its autonomy plan is off the table”, Bennis said. “The most it can offer is the autonomy plan.”

According to Bennis, Spanish sovereignty over Western Sahara was “null and void”, because the territory had been recognised as an indivisible part of Morocco in the 1895 Anglo-Moroccan Treaty signed with the Britain.

Morocco has also argued that the territory is part of a pre-colonial “Greater Morocco” that was then divided up between colonial powers France and Spain.

The Sahrawis, on the other hand, were historically made up a number nomadic tribes native to the region, which did not adhere to strict geographical boundaries. However, some of these tribes swore allegiance to Moroccan sultans.

Sahrawi calls for independence emerged as they settled in cities in the mid-20th century in what was then Spanish Sahara amid a phosphate-rush, giving up their ancient nomadic way of life.

The Polisario Front was founded in 1973 to fight against the imperial government of General Franco before going on to dispute Moroccan claims to Western Sahara.

The competing claims to the territory were put to arbitration at the International Court of Justice, which concluded in a non-binding decision that while Morocco did have legal ties to the territory, this did not imply sovereignty, nor did it prevent indigenous people from seeking self-determination.

Two weeks later, Moroccan troops crossed into Western Sahara, sending the Spanish into an end-of-empire panic and leading to a secret agreement between its government, Morocco and Mauritania (also posessed of dreams of a "Greater Mauritania"), which was signed in the last week of Franco's life and cut Polisario and the Sahrawi people out of the equation.

From there, it was war, with cease fire between Morocco and Polisario coming only 15 years later in 1991.

Violations and abuses

The pictures and videos collected by Mansour and his team are published on the website of the Nushatta Foundation, which documents human rights abuses in Western Sahara.

They are forced to meet under cover of darkness because “their work is hated by Moroccan authorities,” Mansour says.

He and other activists have reason to be careful. When he was 19, police arrested him in front of his school, took him out of Laayoune and tortured him by stripping him naked and beating him with sticks in the open air.

In the last few weeks, members of his organisation have also been arrested and had their video equipment confiscated by police.

Peaceful activism is made all the more difficult because Morocco considers Western Sahara its own territory and has outlawed calling for independence or flying the Sahrawi flag.

Moroccan authorities have a brutal legacy of committing human rights abuses, including the use of napalm on civilian populations and the disappearing of hundreds of Sahrawis. In 2015, a Spanish judge upheld genocide charges against 11 Moroccan ex-officials.

According to Ahmed Benchemsi from Human Rights Watch, the bulk of rights violations nowadays often consist of attacks on the right to protest and the right to free speech.

“You can't express views that are in favour of self-determination in the public space. Protests are broken up quite regularly, " Benchemsi told MEE.

"They can apply soft pressure by denying or threatening to deny people in favour of self determination from social benefits", he adds, referring to monthly payments in social aid granted to Sahrawis in Western Sahara.

"Because Morocco is not a democracy, people who request the right to self-determination and express their desire to not belong to Morocco are deemed unacceptable to authorities".

Despite this, Mansour vows to not let the younger generation of Sahrawis in Western Sahara face what he has faced.

“I am totally frustrated. I cannot imagine letting the current generation face the same fate. It is a condition where they will not be able to speak or express themselves."

He is the third generation of his family to live under Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara, which accounts for 80% of what the United Nations considers a “non self-governing territory.”

The Berm, a long wall of sand and stone lined with millions of landmines, separates the Moroccan-administered side from the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) - or the "liberated territories", as Sahrawis also call it - ceded to Polisario by Mauritania in 1979 and governed by the liberation movement ever since.

At 2,700km, the wall dwarfs Donald Trump’s proposed border wall with Mexico, and surpasses the distance between Paris and Moscow.

Morocco’s annexation of the territory is not recognised by the international community, while the SADR has some international recognition and is considered a full-member state of the African Union.

"Red-line"

But Morocco has powerful friends. According to a diplomatic source familiar with the Geneva talks, American pressure could be tilting negotiations in Morocco’s favour.

The source said that after the first round of talks in December, the Americans pressured Kohler to persuade Polisario to agree to Morocco’s autonomy plan.

When Polisario met with Kohler for talks in Berlin after the first round, “Kohler told them that independence is off the table. Take this plan and sell it to your people,” the source said.

The Polisario Front pushed back, telling Kohler that this was a “red- line” – the Sahrawi people would never accept this.

According to the diplomatic source, the real negotiations are taking place in secret far away from Switzerland - in Washington DC - between the Moroccans, the Americans and Kohler. “The Geneva talks are in danger of becoming a bit of a show.”

The source suggests that Guterres’ optimism stems from American involvement in a process that has been long-neglected by the international community.

“It has become an issue the international community and international media have appallingly overlooked, so once you have a major player involved it is a lot easier for Guterres to talk about the possibility of finding a solution.”

The other major player is Algeria, which has long offered unconditional support to Polisario in terms of arms, aid and training, as well as playing host to 150,000 refugees from Western Sahara.

Bennis, the Moroccan analyst, claimed that there won’t be a settlement without Algerian involvement because “Polisario would not exist without Algeria's military, diplomatic and economic support.”

Having Algeria on side, according to Bennis, would help to overcome divisions within the UN Security Council.

“There has always been division among the permanent members of the Security Council. Some support Morocco, some support Algeria. Assuming that the US, France and UK agree to impose the Morocco autonomy plan, it would face Russian veto.”

But Algeria continues to firmly back the Polisario Front, the diplomatic source said. In response to pressure brought to bear on Polisario to accept the autonomy plan, Algeria hit back, unequivocally stating that “independence has to be one of the options, self-determination has to be a genuine choice.”

The resignation of Abdelaziz Bouteflika last week is unlikely to change this position, the source said, because support for Polisario is a position of the FLN, Algeria’s ruling party, which led the revolutionary war against France.

“Algerian support is deeply ideology, it’s more do with supporting revolution across the world. It’s not linked to particular individuals,” the source said.

But if the FLN - which has dominated Algerian politics for more than 50 years - does fall, then there could be a “dramatic change”, the source said.

Meanwhile, Mansour is drawing political and life lessons from Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

He compares the inner war the young prince goes through as he plans whether to avenge the death of his father with the inner conflict he endures in the face of Moroccan oppression.

“We are not able to act and respond to Moroccan violence, because we believe it’s not the right way. However, we’re not sure if we will keep fighting like that.”

He then asks: “Are we going to have a miserable and tragic ending?”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.