What made Turkey change its Syria policy?

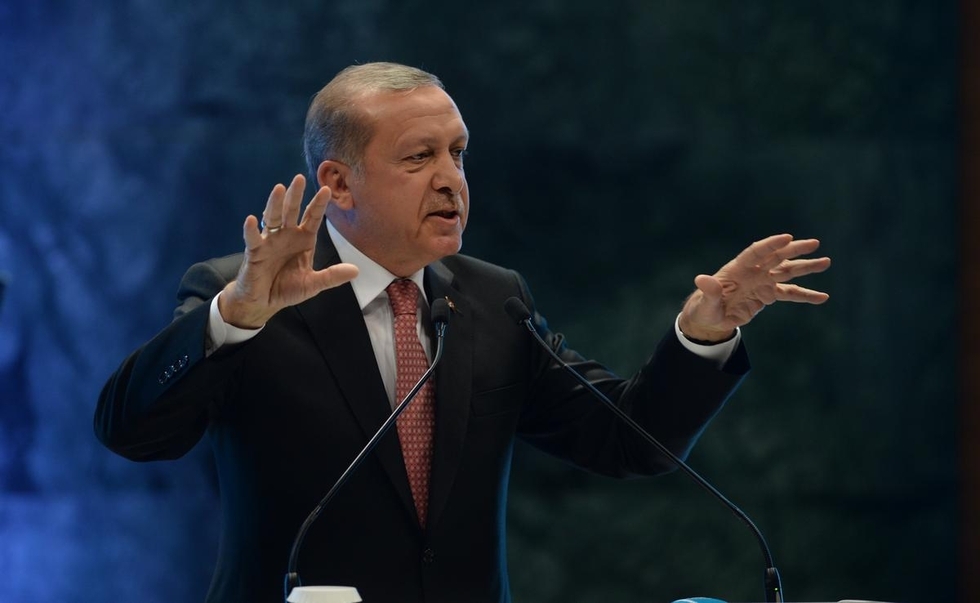

ISTANBUL - When Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan announced in September that Turkey is open to the idea of Bashar al-Assad temporarily being part of a political solution to the conflict in war-ravaged Syria, it came as a major surprise to political observers who have become accustomed to Ankara’s tough line that the removal of Assad is the top priority.

Analysts critical of the Turkish government believe this shift hasn’t come about as a result of an acceptance that policies based on sheer ideology have failed, but rather because the government’s hand has been forced and made it increasingly irrelevant in the Syrian theatre.

Other analysts, however, suggest it is simply pragmatic diplomacy and nothing more than an act of fine tuning established policies to deal with realties on the ground while not deviating from core principles.

Murat Yesiltas, director of security studies at the pro-government SETA Foundation, said there is no major shift in policy and does not in any way represent a move where Turkey suddenly favours any Assad involvement.

“It is a tactical nuance rather than a huge change. Turkey has had to respond to the situation,” Yesiltas told Middle East Eye.

“Ankara needed to adapt, given Russian military involvement, US ambiguity toward the Syrian opposition and a lack of consensus among the great powers, which include France, Germany, Saudi Arabia and Turkey as well.”

Although there are some elements of pragmatic decision making involved, it is not because of self-reflection on failed policies but due to the consequences of what is happening, said Ahmet Kasim Han, an academic at the international relations department at Istanbul’s Kadir Has University.

“Whatever policy shift is taking place is because it is being dictated by the choices and actions of third parties and not because of any ideological change of heart. That would require admitting to policy failure, but no one in the government thinks their policies were wrong at all,” Han told MEE.

“They [the government] were pushed to accept policy change to an extent because they were no longer able to impose their will and risked being left on the periphery of events.”

Turkish views 'adrift' from US and Russia?

Divergent views between Turkey and its Western allies, and also between Turkey and Russia, the other major power involved, on who poses the greater threat have meant that Ankara has often found itself isolated with its positions.

The West, led by the US, and Russia both see IS and other such groups as the foremost threat, whereas for Turkey the major threat is the dissolution of its southern neighbour potentially leaving it faced with a left-wing Kurdish state run by the Democratic Union Party (PYD). Ankara considers the PYD a terrorist entity and a wing of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party with which it has been involved in a war since 1984.

Turkey has all along considered the ouster of Assad as the best option to maintain Syria’s territorial integrity and thereby prevent the PYD from fully establishing itself in the north of the country. The United States, however, has gradually shifted its stance and is willing to entertain the thought of allowing Assad to remain at the helm until the IS threat is dealt with.

Turkey could find itself adrift from both the US and Russia if - despite all differences between the two countries on Assad’s future - they agree to put that aside momentarily to tackle IS.

“The vital issue to consider here is that Turkey views ISIL (Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) [an alternative term for IS] as a consequence of the Syrian regime’s oppression and believes the root of the problem needs to be tackled first,” said Yesiltas.

In Yesiltas’ opinion, IS poses a real threat to Turkey both along its border and also internally. But he said the PYD is also a threat and not one that Ankara can ignore. He added that Turkey is receptive to all initiatives that negate all these threats.

“Turkey has no desire to see the emergence of another quasi state in the region, particularly a PYD one which is attempting to change the demographic composition in the area,” said Yesiltas.

What is Turkey's top priority?

The fact that Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu continued to insist that the ouster of Assad should remain the top priority during his visit to the United Nations General Assembly and in his speech there on 30 September, while seemingly in contradiction with Erdogan’s statement, could actually signal that while Ankara might be willing to reconsider its priorities, it will nevertheless also continue to push for what it still believes is the soundest way forward.

Erdogan’s spokesman and advisors were quick to suggest that Erdogan’s remarks did not signify a policy shift and Davutoglu himself was at pains to state that Turkey’s Syria policies have not been static over the years and that Turkey’s position has not changed.

“There is no gulf in the views held by the prime minister and president. Turkish political strategy is clear and any such appearance is due to the different personal characters of the two men. It is simply a matter of nuance,” said Yesiltas.

According to Han, these contradictory stances and statements are not due to any rift but because the government has played the foreign policy card so strongly in the domestic political arena that it now finds itself firmly entrenched in such ideologically motivated policies and doesn’t know how to extricate itself without losing domestic political capital.

“Any pragmatism being displayed is due to their vested domestic political interest. This is just an exaggerated version of the adage that all politics is local,” said Han.

The seemingly abject failure of the joint effort by Turkey and the United States to train and equip rebel fighters, and the tepid response at best to Ankara’s wish to establish what it calls safe zones in Syria also potentially lie behind this shift in policy on Syria.

“Realities on the ground have pushed them toward such a change but they basically see nothing wrong with their original policies. Any failure is attributed to the incompetence of other actors and allies such as the United States,” said Han.

“In the end it depends on the entire international coalition, and not just Turkey, if any political solution is put on the table, whether that involves Assad or not,” said Yesiltas.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.