What's next for the Moroccan left?

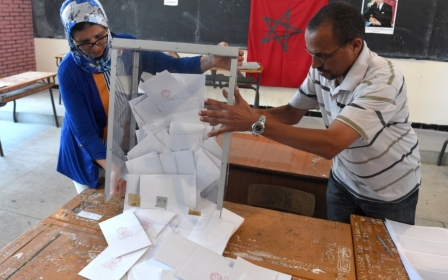

RABAT - The Democratic Left Federation (FGD), a coalition of three so-called “radical” left-wing parties in Rabat, came second in the Agdal Riad constituency, a rather affluent district of the Moroccan capital, during the recent communal elections. Overtaken by the Islamists of the Justice and Development Party (PJD), the FGD nevertheless managed to get nine municipal councillors elected, five women and four men.

However, even combined, these three parties - the Socialist Democratic Vanguard party (PADS), the National Ittihadi Congress Party (CNI) and the Unified Socialist Party (PSU) - have usually put in a weak electoral performance. In the rest of the country, the federation achieved no significant breakthrough, getting barely over 100,000 votes, while 1.5 million people voted for the Islamists of the PJD. In Casablanca the PSU’s general secretary Nabila Mounib failed to win over the electorate.

Nevertheless, this coalition has generated real enthusiasm, particularly among left wing activists and party members. FGD leader Omar Balafrej, who is not a member of any established political party, does not see this as a victory but as a "first step". His goal is to offer a third option as an alternative to the Authenticity and Modernity Party (PAM) - close to the monarchy and created to counter the Islamists - and the Islamists of the PJD, who have made significant progress in major Moroccan towns and cities. Balafrej’s task will nevertheless be a difficult one, as the left in Morocco is extremely divided and the issues dividing them are significant - including the constitution and the power of the monarch, economic reforms and more. The left is also divided by ideological differences that may be difficult to reconcile.

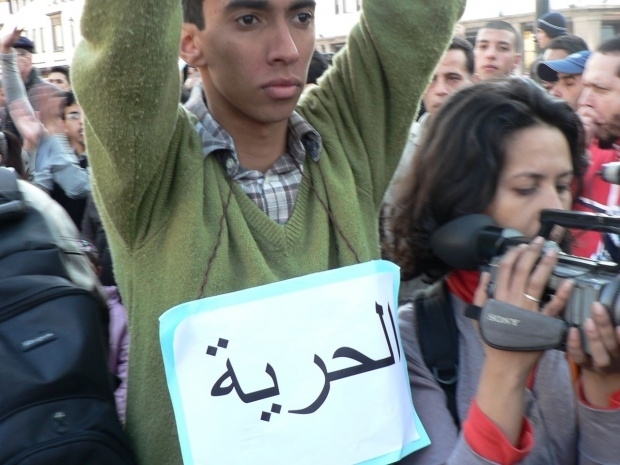

Boycotting the elections

In recent weeks, the bone of contention has been participation in the election itself. Among activists on the far left, this recurrent subject has generated passionate debate, just as it always has. Within the PSU, part of the party's youth wing was initially opposed to participating in the election. But above all, elections are boycotted by those who declare themselves as having a left-wing outlook, but who are members of no political party.

The members of the Marxist party Annahj Addimocrati (Democratic Way), which has not taken part in any election since it was created in 1995, once again campaigned for a boycott (their meetings have been banned by the authorities on several occasions). The call for boycott was supported by activists from ATTAC, Maoists and a number of independents.

In their view, the electoral process does not work democratically in Morocco. Among other things, they condemn the buying of votes and stress that there is no guarantee of transparency in the elections organised by Morocco’s Ministry of the Interior.

"There are several dynamics in what we generally refer to as the left,” explained Mohamed Jaite, a member of the Annahj Addimocrati party.

“There is a powerful dynamic launched by the boycott campaign within Annahj. There is also a dynamic launched within the FGD but how is this likely to develop? I have no idea," Jaite told Middle East Eye.

"The historical experience suggests to me that they are chasing illusions,” he continued. "I believe that the necessary precondition to build a left-wing political force which can achieve something in Morocco is independence from the palace. I feel that the current FGD leadership lacks independence from the monarchy.”

Younes, a former member of the PSU and an activist within the 20 February protest movement, which called for more democracy and respect for the state of law in 2011, has only voted once, in 2007. He has boycotted all elections since then. His view on these elections sums up the viewpoint of many activists. "When I campaigned for the boycott, I felt rather guilty as I saw honest genuine people who thought that they could change things," he told MEE.

"I don't agree with them. I believe that they can't change things from inside. I have faced the facts and we need to be realistic. The same people now participating in the elections boycotted those of 2011. They have weakened the boycott and ultimately have achieved nothing."

He added: "The election system and the institutions can be seen as a software programmed by the makhzen [the "store," - an expression used by the Moroccans to refer to the monarchy and its institutions] which is not intended to bring about democracy."

Major divisions on the left

The Moroccan left has been fragmented for several years now and there is no sign of anything uniting it any time soon. Major ideological differences originating from Morocco’s recent history persist and have resulted in a number of missed opportunities.

The USFP, a genuine opposition party in the days of Hassan II, is now only a shadow of its former self. As for the Party of Progress and Socialism (PPS), although it is holding its place electorally, it is seen as an establishment party. It also participates in the governmental coalition. For many people, these two parties are now ideologically light-years away from the left.

The fracture within the far left is, however, more problematic. But when united, it has achieved results, especially with the 20 February Movement but also within the Moroccan Association of Human Rights (AMDH), one of the most influential organisations for the protection of human rights in the region and during the protest movement against rising living costs a few years ago. Nevertheless, in the opinion of numerous observers, a genuine political union is impossible.

In this context, can the new FGD be a voice for change on the left? It has created a fresh dynamism which is truly perceptible on the social networks, and led a campaign which attracted praise from many observers, with new faces emerging and real outreach work.

At the PSU headquarters in Casablanca, large numbers of activists turned out to lend a hand. Among these, some were not card-carrying members but were keen to give it a go. Others came along even if they did not intend to vote.

But throughout the campaign, the same questions arose: why take part in the elections now when no real political and institutional change has occurred (as they see it) in recent years? Does the PSU’s participation in the election, despite the fact that it opposed the constitutional referendum in 2011 and boycotted the parliamentary elections the same year, risk transforming the PSU over the long term into a party absorbed by the makhzen?

Two years ago, Younes and a group of activists were side-lined by the leadership of the PSU for expressing disagreement. He then went on to resign.

"This was a turning point. But the first reason I left was because the PSU was acting contrary to the logic of the 20 February movement almost as if this movement had never existed. I was in the PSU when it worked with the movement," he explained.

"But when the movement began to weaken, it became a party just like the others. I fear it might think it's in the process of being tamed by the makhzen, just like the USFP."

Mohamed Boulaich, a former member of the Marxist-Leninist movement Ila al-Amam (Forward), chose not to vote, simply because no party met his expectations - even the PSU, the party for which he campaigned for a decade. "We firstly need to change the constitution. The king should reign and not govern. This is the only plausible way forward," Boulaich said.

Out of the blue

Today, Boulaich does not believe that a political alternative will emerge from the ballot box.

But "there can always be a surprise," he told MEE. "Did anyone really expect to see the 20 February movement emerge? Not at all! It came out of the blue! The 20 February movement has done a lot and has had a positive impact on national life. People aren't afraid anymore and avenues have been freed. Everyone can demonstrate. [The demonstrators chanted] impressive slogans to show their opposition to the dictatorship and to the repression.”

"Unfortunately, the forces of the left did not rise to the occasion. Their approach was too calculating. They didn’t want to go that far and simply saw the possibility to pick up some members. Instead of going all the way with the movement, they simply saw a market for new members."

Abdullah Abaakil - a former Casablanca activist with the 20 February movement who was once part of the USFP, which he left in 1995 - chose to support the FGD. In his view, the left needs to open up and to attract those who are "culturally close to it" if it wants to survive. "The fundamental objective is to state clearly that we are alive and kicking and that we are still here."

He feels that the FGD can create an alternative on the left without needing to expand its political alliances.

"Politics is not a question of arithmetic,” Abaakil said. “And sometimes you lose by adding more. I believe that in its current form the FGD does not necessarily need to create other alliances but instead it needs to reinforce those already existing.”

This article was originally published on Middle East Eye's French page on 11 September 2015.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.