Kuwait's Sheikh Sabah: The Gulf's 'great balancer'

The death at 91 of the Kuwaiti Emir Sheikh Sabah al-Ahmad al-Jaber al-Sabah brings to a close nearly 60 years of service to his country. He was Kuwait’s second foreign minister, a post he held from 1963 to 2003. In 2003 he was appointed prime minister, a position he held until being named emir in 2006.

Sheikh Sabah became emir after his second cousin had succeeded Sheikh Jabar al-Ahmed al-Sabah, but had proved medically incompetent and was removed after just nine days. In his 14 years ruling Kuwait, Sheikh Sabah won international plaudits for his humanitarian undertakings and his efforts to serve as a mediator in disputes between fellow Gulf states.

'Sheikh Sabah's greatest role has been in mediating the Gulf crisis, delicately and untiringly, despite his age and enormous pressure to pick a side'

- Dr Alanoud Alsharekh, women's rights activist and academic

His efforts on the domestic front were entangled in the continuous struggle between the ruling family and Kuwait’s parliament, known as the National Assembly, one of only two among the Gulf states and the oldest, having been established two years after the country’s independence from Britain in 1961.

For many years, and particularly in the West, the so-called “Kuwait model” was viewed as a guiding light for other Middle East and Gulf states, a best practices example of how a traditional society run on tribal lines could move along the road to democratisation.

Under the 1962 constitution, the emir appoints the prime minister who appoints the ministers. A majority of the elected deputies have the authority to remove confidence in ministers, including the prime minister, something no other Gulf state allows.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The prime minister, however, is always a member of the ruling family. And though the momentum has swung back and forth since 1963, the bulk of the power in the political system has been retained by the Al Sabah family. The academic Michael Herb, an expert on Kuwaiti constitutional matters, notes that the National Assembly has been left to exercise what he calls a “negative power bringing down ministers it doesn’t like. And that creates all sorts of crises and problems”.

Sheikh Sabah was very familiar with that negative power, having experienced it and responded by dissolving parliament multiple times. Indeed, in the first seven years of his rule, Kuwait experienced six dissolutions and six elections.

The most recent dissolution, the seventh, was in 2016. Opposition members had filed requests to challenge ministers on an increase in petrol prices and allegations of financial and administrative irregularities. The emir’s response was swift. Citing economic and security concerns he shut the National Assembly down, thus triggering new elections.

Since then, however, either because opponents were jailed or have left the country, some after being stripped of their citizenship or because Kuwaitis themselves have grown tired of a parliament of negative power, there has been a period of calm. For the first time in many decades the current National Assembly will see out its term, with new elections scheduled for November of this year.

Geopolitical headwinds

It is in foreign affairs, however, that Sheikh Sabah’s ultimate legacy rests. In the work he did in regional diplomacy, both as foreign minister and emir, he advocated and navigated a middle path for Kuwait through often difficult and challenging times: the Iranian revolution of 1979, the subsequent Iraq-Iran war, the threats of Saddam Hussein that culminated in the 1990 invasion, the liberation of 1991 and the return of the ruling family with the challenge of rebuilding the country’s war-damaged infrastructure.

In this century, Kuwait was again threatened by events in neighbouring countries. In Iraq it was the insurgent wars of the noughties and in this decade the sudden emergence of the Islamic State group (IS). The decision in 2018 by US President Donald Trump to withdraw from the JCPOA, the nuclear deal with Iran negotiated by his predecessor Barack Obama, has occasioned further tension and instability in the region.

In regard to the JCPOA, the emir, while expressing understanding for the US withdrawal, did not support the decision as vociferously as fellow Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) members Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain. It was one example of why Sheikh Sabah has been called “the great balancer”. Another is Yemen, where Kuwait initially backed the Saudi- and UAE-led coalition and then subsequently offered itself as a mediator, though thus far without success.

Nowhere has the balancing act been more in evidence than in the efforts the emir put into attempting to resolve disputes within the GCC.

The Kuwaiti women’s rights activist and academic Dr Alanoud Alsharekh concurs: “Sheikh Sabah's greatest role has been in mediating the Gulf crisis, delicately and untiringly, despite his age and enormous pressure to pick a side.”

She also pointed to his response to the IS-claimed bombing of Imam Sadiq Mosque in Kuwait City in 2015: “He was inspiring in his courage and compassion when he rushed to the bomb site where Shia Kuwaitis were killed in a terrorist act as they prayed, ignoring safety and security concerns to send a clear message that sectarian violence has no place in Kuwait.”

Key intervention

The GCC disputes almost invariably revolved around Qatar. In 2014, Sheikh Sabah intervened successfully to end a diplomatic row between the Qataris on the one hand and Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain on the other.

In March of that year, the latter three had withdrawn their ambassadors to Doha, principally at the instigation of the Saudis who resented both the Al Jazeera network and Qatar’s energetic and independent foreign policy approach under then prime minister and foreign minister Hamad bin Jassim. With the skilful intervention of Sheikh Sabah, relations were restored eight months later.

Within three years, however, the GCC was torn apart when in June 2017 the UAE, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and Egypt broke off diplomatic relations and imposed a land, air and sea blockade on Qatar. There was an imminent risk that Qatar would be invaded.

Sheikh Sabah, mindful of the terrible impact of Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990, embarked on a whirlwind of shuttle diplomacy in the first three days of the dispute. At the age of 88, in the midst of Ramadan and at the height of summer he went to Doha, to Abu Dhabi and to Riyadh.

Historian and analyst Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, author of Insecure Gulf: The End of Certainty and the Transition to the Post-Oil Era, calls it “his biggest legacy… he stopped it from escalating, he did not resolve [the dispute] but he stopped it from going further”.

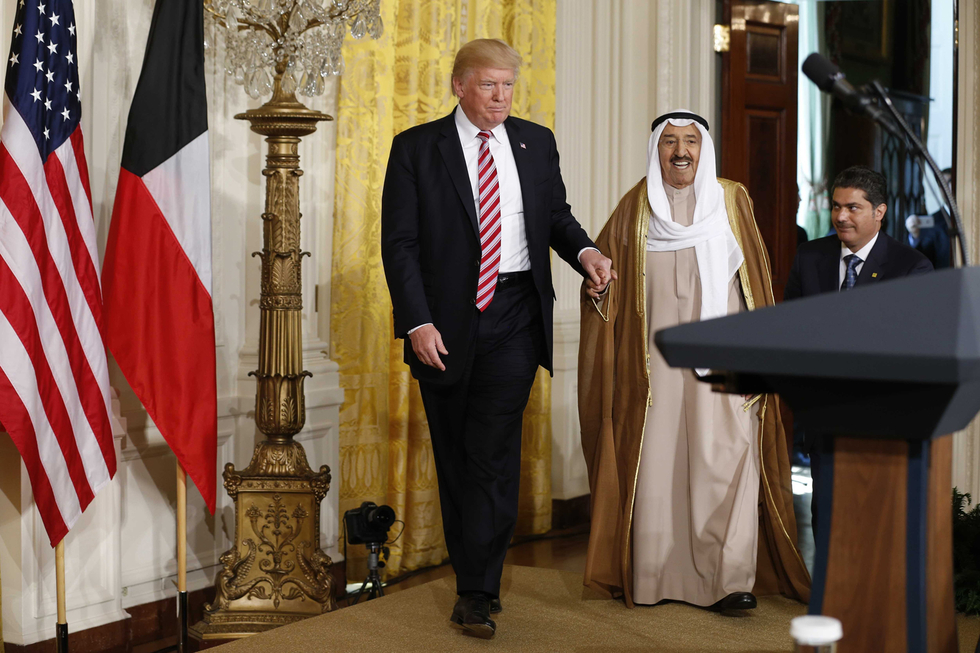

As the emir himself said at a White House press conference with Trump in September 2017: “Thanks [to] God, we averted military action.”

It was a matter of great regret to him that despite his repeated efforts, which included involving the United States in pressuring the parties to end the feud, the Qatar blockade remained unresolved.

Sheikh Sabah's 83-year-old half-brother, Crown Prince Sheikh Nawaf al-Ahmad al-Sabah, has been named as his successor.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.