World Cup 2022: Morocco defeat is music to Sahrawi ears

As Morocco’s unprecedented 2022 World Cup run ended in a semi-final defeat at the hands of France, Sahrawis in Laayoune took to the streets to celebrate, waving flags, driving doughnuts in their cars, and calling out in joy.

These weren't the celebrations Moroccan authorities had hoped for.

In Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara loyalties are divided. Some 600,000 people live in the territory, with Moroccans originally from elsewhere estimated to be in a slight majority. Yet the indigenous Sahrawis are estimated by many to favour independence.

It can be hard to tell: Moroccan authorities crack down on displays of Sahrawi nationalism. Even speaking the Sahrawi Hassaniya dialect can get you in trouble.

So, for pro-independence residents of Laayoune and other cities, Morocco's defeat in football became an opportunity for self-expression and support for the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), a breakaway state based in the 20 percent of Western Sahara held by the Polisario Front armed movement.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

'Moroccan authorities always use sport to spread official propaganda about Africa's last colony'

- Ahmed Ettanji, Equipe Media

Mohamed Mayara, a 47-year-old Sahrawi, watched the game with his family at home in the capital of Moroccan-administered Western Sahara.

“I didn’t celebrate outside because I was afraid of the reaction of the Moroccan settlers, police, and paramilitaries, but I saw friends go out to celebrate, I saw Sahrawis in their cars, waving the SADR flag, and I heard a lot of noise,” Mayara said, referring to the local Moroccan population, who are considered settlers by some Sahrawis.

Not all Sahrawis wanted Morocco to lose. Mayara knows some supporting Morocco - though he said they tend to keep their loyalties quiet - and other Sahrawis were seen celebrating previous victories in the streets alongside Moroccans.

One Sahrawi youth in Laayoune was quoted by the AP as saying “the historic success of the Moroccan national team” had created a collective feeling of “overwhelming joy that included all Arabs and Africans, despite the constant discontent with the Moroccan state”.

Mayara, who said it was important to recognise that he was supporting a Moroccan defeat, not a French victory, was not alone in worrying about the Moroccan response to any Sahrawis celebrating the team’s defeat.

After the final whistle, a fight erupted in a cafe in Laayoune between Sahrawis celebrating the Moroccan defeat and Moroccans.

Several Sahrawis told MEE a Sahrawi boy was beaten badly and had to be taken to hospital. The police closed the cafe and arrested the Sahrawis present.

Worldwide support

The response to Wednesday's game, which Morocco had the better of for large periods but which France won 2-0, highlighted some of the complexities behind the North African side's inspiring World Cup journey.

The first Arab and African team to reach the semi-final of the tournament, Morocco has drawn support from across the world along the way. It’s been a classic underdog story and the team will leave Qatar as heroes across the Arab world, Africa, and beyond.

“No matter who you’re rooting for, it was remarkable to watch how much this team has been able to achieve,” US President Joe Biden tweeted after the semi-final, which he watched with Morocco’s prime minister, Aziz Akhannouch. French President Emmanuel Macron is even said to have gone into the Moroccan dressing room to tell Morocco's Sofyan Amrabat that he was the “best midfielder of the tournament”.

On their way to the semi-final, Morocco’s players have celebrated their various victories - including against former colonial powers Portugal and Spain - by draping themselves in the Palestinian flag, a move seen not just as a mark of solidarity but also as a popular rebuke to the kingdom’s normalisation of relations with Israel.

But while Morocco’s World Cup heroics have been lauded for forging a new identity that reflects Morocco's Arab, African and Amazigh natures, many Sahrawis have felt their place in this story has been left out.

Worse than that, while Morocco’s players have shown their solidarity with the Palestinian cause and opposition to the Israeli occupation, they have also been filmed singing that “the Sahara is ours, its rivers and land are ours”.

And, according to a number of Sahrawi activists and journalists, the World Cup has seen an upsurge in incendiary rhetoric and physical violence targeting Sahrawis living in Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara, as Moroccan nationalism ramps up.

Exile and war

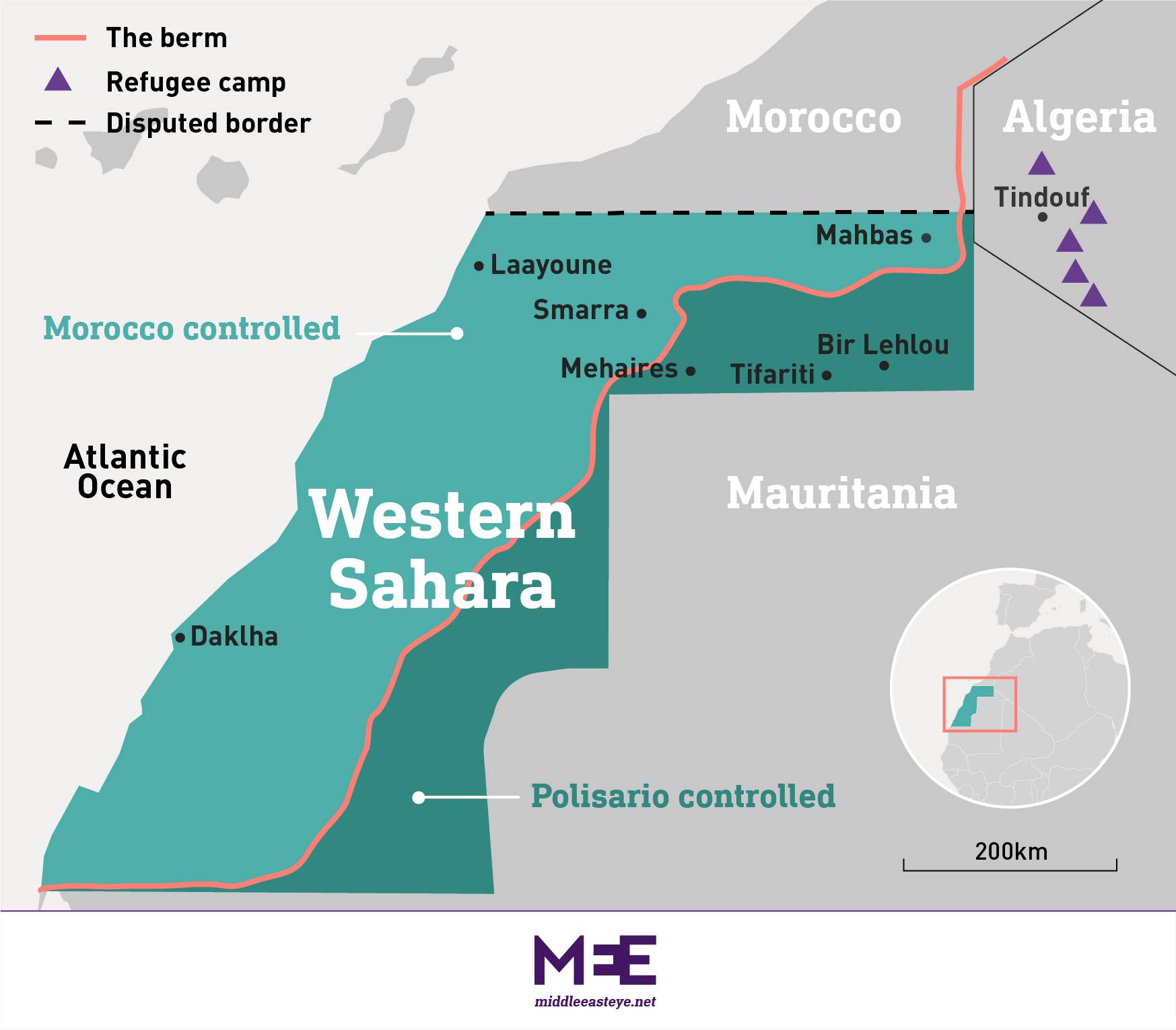

Formerly the Spanish Sahara, the lands making up Western Sahara were occupied by Morocco and Mauritania in 1975. A war ensued between the countries and the Polisario Front, Western Sahara’s armed independence movement. But while Mauritania was forced out and a ceasefire with Morocco brokered in 1991, a promised referendum on Sahrawi independence never materialised.

Today, over 173,000 Sahrawi refugees live in refugee camps in Algeria, according to the UN. About 10,000, meanwhile, lived in the 20 percent of Western Sahara held by Polisario, until the conflict renewed between the group and Morocco in 2020 and most of them fled.

Pro-independence Sahrawis describe Morocco's control of Western Sahara as an occupation.

The UN describes the territory's status as "non-decolonised". And while many Sahrawis see their own struggle reflected in the Palestinian struggle, and some Palestinians similarly return solidarity, Mayara described the flying of the Palestinian flag by Moroccan players and fans as a "typical double standard”.

“We are also the victim of a long history of cooperation between Morocco and Israel,” he said, referring to the Israeli surveillance tech and drones purchased by Rabat, as well as to the Donald Trump-brokered deal that saw the US recognise Morocco's sovereignty in Western Sahara in exchange for normalisation of ties with Israel.

Ahmed Ettanji, a Sahrawi from Laayoune and co-founder of Equipe Media citizen journalist group, said the World Cup served as a chance to push its national line on a global stage.

“Moroccan authorities always use sport to spread official propaganda about Africa’s last colony,” he told MEE. “Unfortunately, a lot of people are not aware of the conflict in Western Sahara.”

In the run-up to the France game, Moroccan social media accounts, some with as many as 70,000 followers, posted messages calling for attacks on Polisario if Morocco won the game. In one video, a Moroccan on TikTok said Moroccans should celebrate beating France by “attacking Polisario”.

Some Sahrawis perceived the threat to attack Polisario as a dog whistle for all pro-independence Sahrawis.

“I think it is a campaign because there are videos and photos and comments - thousands of comments - calling for Moroccan settlers to attack Polisario, meaning Sahrawi people, in the occupied territory if they won,” Nazha el-Khalidi, a Sahrawi journalist and activist, told Middle East Eye.

Tense atmosphere

Pro-independence Sahrawis described a tense atmosphere in Morocco-held Western Sahara throughout the tournament, particularly Laayoune. "There are police and paramilitary forces present, and checkpoints. The Moroccans have brought thousands of people into the centre of the city to celebrate after games,” Ettanji said.

Sahrawis also recalled the treatment meted out to them for supporting Algeria at the Africa Cup of Nations in 2019. Polisario is backed by Algeria, which is Morocco's greatest rival on the world stage. Currently, the neighbours do not share diplomatic relations.

Western Sahara explained

+ Show - HideWestern Sahara is a largely desert expanse (266,000 sq km) in the northwest of Africa that is bordered by the Atlantic, Morocco, Mauritania and Algeria. Its indigenous people are the Sahrawis, who mostly speak Hassaniya, an Arabic dialect.

The region was colonised by Spain during the late 19th century and later became known as the Spanish Sahara. Morocco, parts of which were also a former Spanish colony, has long made claims on the region.

In November 1975, King Hassan II of Morocco sent 350,000 civilians and 25,000 troops into what was still Spanish territory, as part of what became known as the "Green March".

Fearing that conflict with Morocco would destabilise the government at home, as it had done with other European colonial powers like France (in Algeria) and Portugal (in Angola), Spain rapidly departed Western Sahara, cutting a secret deal with Morocco and Mauritania, the latter of which also claimed close links to the area.

Signed in the last week of fascist leader General Francisco Franco’s life, the Madrid Accords removed the Sahrawis and their chief representatives, the Polisario Front, from the equation. Two thirds of the territory was given to Morocco, and one third was given to Mauritania.

When Morocco and Mauritania entered Western Sahara in 1975, war began with the Polisario Front, and thousands of Sahrawis were forced to flee to refugee camps in Algeria. Their place has been taken by Moroccan settlers, who have been incentivised to move into the region by Rabat and who now make up the majority of Western Sahara's population.

Polisario, which seeks independence for the territory and is backed by Algeria, defeated Mauritania in 1979. The land won in this war is now known to Sahrawis as the "liberated territories", a largely uninhabited stretch of desert to the east of Morocco's 2,700 km-long border wall.

A 1991 ceasefire broke down in November 2020. There has been sporadic fighting since then.

Timeline

1884: Spain declares Western Sahara a protectorate on 26 December. The Spanish meet immediate resistance from the Sahrawis.

1956: Morocco gains independence from France and Spain on 2 March.

1957: At the United Nations, Morocco makes its first modern claim on Western Sahara (certain treaties from the 17th and 18th centuries included Moroccan claims to some of the region).

1958: Spain creates the overseas province of Spanish Sahara on 10 January.

1966: Creation of the Harakat Tahrir, or the Movement for the Liberation of Saguia al-Hamra and Wadi al-Dhahab. It campaigns for a peaceful end to Spanish rule and self-determination for Western Sahara.

1970: A Harakat Tahrir protest in Laayoune on 17 June is brutally suppressed by Spanish forces, resulting in at least 10 deaths and hundreds of injuries. The movement disbands.

1973: Creation of the Polisario Front on 10 May to represent the Sahrawis.

1974: Spain announces on 20 August that it will hold a referendum to decide the future of the region in the first half of the following year. Morocco rejects the idea. The UN asks the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for an advisory opinion.

1975

16 October: The ICJ rules in a non-binding decision that while there were legal ties between Western Sahara and Morocco and Mauritania, these did not “establish any tie of territorial sovereignty”; also that such legal ties did not apply to "self-determination through the free and genuine expression of the will of the peoples of the territory”.

31 October: Morocco invades Western Sahara from the north.

6 November: At the urging of King Hassan II, an estimated 350,000 unarmed Moroccans cross into Sakiya Lhmra in support of territorial claims in an event that becomes known as the Green March (below). Spanish troops are ordered to let them pass to avoid bloodshed.

14 November: Fearing conflict with Morocco, Spanish support for Sahrawi self-determination falters. Under the Madrid Accords, Western Sahara is ceded to Morocco (the northern two-thirds of the territory) and Mauritania (the remaining south). While the deal states that the views of the indigenous population need to be respected, no Sahrawi representatives are present at the talks due to Moroccan insistence.

1976: Spain announces its official withdrawal from Western Sahara on 26 February. A day later, the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic is declared by the Polisario Front. With support from Algeria and Libya, it fights on against both Morocco and Mauritania, its forces bolstered by refugees.

1979: After three years of attacks by the Polisario Front, which have destabilised the country, Mauritania is forced to withdraw and renounces its claim on the region on 5 August. It recognises the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic. Morocco takes much of the territory previously controlled by Mauritania.

1980 onwards: Sporadic fighting continues between Morocco and Polisario. A giant sand wall is built between Western Sahara and southwest Morocco to deter attacks by Sahrawis. “The berm” will eventually extend 2,700km and take seven years to complete.

1991: Ceasefire declared on 6 September under the peacekeeping mission United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO). Its purpose is to monitor the cessation of fighting, including the movement of troops on both sides; repatriate prisoners and refugees; and conduct a referendum in 1992. The UN recognises Western Sahara as a "non-self-governing territory".

1992: No referendum takes place, amid a dispute as to who can vote.

1997: The Houston Agreement, coordinated by James Baker, UN representative and former US secretary of state, fails to restart plans for a referendum.

2003: The UN-sponsored Baker Plan, intended to replace the Settlement Plan, stalls amid Moroccan opposition to any referendum.

2020

13 November: The Polisario Front says on 13 November that the ceasefire has come to an end after Morocco resumed military operations in a buffer zone.

10 December: The US recognises Morocco's sovereignty over Western Sahara in return for a Morocco-Israel normalisation deal.

In the Moroccan crackdown on Sahrawis supporting Algeria in 2019, a 24-year-old woman was killed after she was mowed down by two Moroccan auxiliary force cars.

Another youth was severely beaten for wearing an Algeria T-shirt and has since been given a 15-year prison sentence for possession of hashish.

“Nowadays we hear from Moroccan authorities and media that a Moroccan victory is one of Arabs, Muslims, and Africans… Why should Sahrawis be tortured for celebrating the victory of a neighbouring country or club?” Sidi Breika, Polisario representative to the UK and Ireland, told MEE.

Yet that 2019 crackdown clearly didn't dissuade the Sahrawis making noise on Wednesday night.

“We are now celebrating in the streets,” said Khalidi.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.