Algeria's Abdelaziz Bouteflika steps down, ending two-decade rule

Abdelaziz Bouteflika has submitted his resignation after four terms in office, marking the end of a political career that lasted over half a century.

Bouteflika, 82, officially notified the president of Algeria's Constitutional Council of his "decision to end his presidential mandate", his office said in a statement released by the state-run Algeria Press Service on Tuesday.

His resignation is "effective today", the statement said. It also said Bouteflika hopes his decision will bring calm to the country, enabling citizens to "collectively transition Algeria towards a better future".

"I have the honour to formally notify you of my decision to terminate my term of office as President of the Republic from today, Tuesday," state news agency APS quoted his resignation letter as saying.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Hundreds of Algerians took to the streets of the capital after Bouteflika's resignation, waving Algerian flags or driving in convoys through the city centre, Reuters reported.

"Allahu Akbar (God is Great)," shouted a man. Someone else held up a banner saying: "Game over."

State TV showed a frail-looking Bouteflika, dressed in a traditional winter robe, handing his resignation letter to the head of a constitutional council. Also present was Abdelkader Bensalah, chairman of the upper house of parliament, who will run the country for 90 days until elections are held.

"I have taken this step because I am keen to put an end to the current bickering," Bouteflika said in a letter released on state media, using his main means of communication since suffering a stroke in 2013 and largely disappearing from public view.

The Algerian president would have liked to leave the post only on his deathbed, his own end tied to the conclusion of a chapter in Algeria's history.

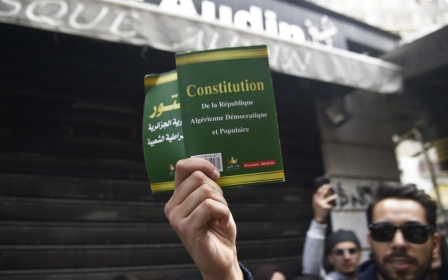

But hundreds of thousands of Algerians have taken to the streets since mid-February to protest against Bouteflika running for a fifth term in office, calling for his removal and the government's.

While Bouteflika initially remained defiant against popular pressure and submitted his bid for re-election, he then dropped out of the race, only to cancel the vote altogether on 11 March.

Three weeks later, on 1 April, the elderly head of state announced that he would step down by 28 April, the official end of his term.

Since his stroke in April 2013 and his 80-day hospitalisation in France, Bouteflika has officially continued to perform his duties despite rumours that he was dead and speculation about his ability to lead the country.

Physically diminished, seated in a wheelchair and speaking with great difficulty, Bouteflika had in recent years created an illusion of statemanship by receiving foreign chiefs of state and ministers on official visits in front of the state-owned news outlets.

His aides and the diplomats he met have repeatedly claimed that Bouteflika was "in his right mind".

But the demonstrators have changed a situation that, until just a few weeks ago, seemed secured by the state's political apparatus, and a call from army chief of staff Ahmed Gaid Salah on 26 March to remove Bouteflika only hastened his exit.

The rise to power

Born on 2 March 1937 in Oujda, Morocco, to a family from Tlemcen in western Algeria, Bouteflika in 1956 joined the National Liberation Army (ALN), which led the war against France from 1954 to 1962.

While he holds the record for longest-serving Algerian president with 20 years in office, Bouteflika was also once the country's youngest minister.

In 1962, when he was only 25 years old, he was appointed minister of youth, sports and tourism. A year later, in 1963, Ahmed Ben Bella, Algeria's first president following the country's war of independence from France, named him as the minister of foreign affairs.

The ambitious young politician believed he was the successor of Houari Boumediene - the chairman of the Revolutionary Council of Algeria and the country's second president. Bouteflika thought that after Boumediene's death in 1978, he could take over the presidency, but the army blocked his way.

Leaving the country amid accusations of embezzlement, he then spent many years in the United Arab Emirates and Switzerland before the Algerian army allowed him back to join the FLN in 1989.

After refusing the military's request to lead a transitional government in 1994 - three years into a bloody civil war - he returned to politics in 1999, running as an independent candidate backed by the army after then-President Liamine Zeroual unexpectedly resigned.

The only candidate to run after all other opponents dropped out of the race, citing fears of fraud, Bouteflika won 74 percent of the vote, making him the country's fifth president.

Perfect timing

The timing was perfect for Bouteflika.

While Algeria's civil war did not end until 2002, the "black decade" of the 1990s saw some 200,000 people killed, according to tallies by NGOs.

However, with the Charter for Peace and National Reconciliation that was adopted by referendum in September 2005, the president established himself as a peacebuilder.

"The national reconciliation project took precedence over political and economic reforms because the president has clearly understood that Algerians' 'social conscience' was focused on order and attaining social peace," Noureddine Hakiki, director of the Laboratory for Social Change at the University of Algiers 2, told Middle East Eye.

Bouteflika also rose to power during an era of skyrocketing oil prices.

In the 2000s, oil generated billions, making it possible for Algeria to repay external debt ahead of schedule, accumulate nearly $240bn in foreign exchange reserves, and, above all, turn its oil revenues into a source of unbridled social welfare.

There were subsidies on commodities, support for start-ups, and wage increases. To buy social peace, the president spared no expense, even when oil prices started falling in 2014.

Sixteen years after taking office, Bouteflika achieved what he had promised he would do: remove the military from politics and build a civil state. To do it, he dissolved the Intelligence and Security Department (DRS) - the intelligence services that had been the backbone of the Algerian system - and sent its head, General Toufik, into retirement.

A shadowy figure of whom only two known photos exist, Toufik led the DRS for 25 years and had until then been presented as the other ruler of the dual military-political system running the country.

"From the beginning, he [Bouteflika] had only one idea in mind: to change the system," a member of the president's inner circle told MEE. "And he had told himself that nothing and no one could stand in his way."

With this move, Bouteflika took his revenge on the soldiers who had blocked his career in the 1970s and then brought him to office two decades later.

"Today, people like Nezzar, Belkheir, Touati [generals who had a significant influence in the 1990s] are gone and there will never be any more like them again," the insider added.

"The army's politician-producing machine has been depleted. Ahmed Gaid Salah is the last officer of the ALN to hold the chief of staff position. The next ones will be technicians.

"Thanks to Bouteflika, a whole generation that used historical legitimacy to hold power was driven out."

The man of the past

As early as 1999, Bouteflika vowed to "recover" his "constitutional powers that had been dispersed since 1989". Over that decade, the ruling party conceded multi-party rule in the face of popular protests. But the army ended that political experiment in 1991 at the start of the civil war.

After his return in 1999, Bouteflika used a series of political moves to maintain control in the country - something that bore long-term consequences.

Neither the "black spring" riots of 2001, which erupted after the death of a high school student in a police station in Kabylia, nor society or the generals appeared to stand as obstacles in Bouteflika's path.

A decade later, Algeria also avoided the popular uprisings that swept across the region - thanks to big spending.

"In order to deflect the revolutionary tide of 2011 [across the Middle East], the government boosted public spending by 25 percent," said political scientist Mohammed Hachemaoui. "This measure increased the budget deficit" to 34 percent of the country's GDP, he said.

For Hachemaoui, "the uninterrupted distribution of oil revenues over the past ten years has not been enough, despite its unprecedented volume [$200bn between 2001 and 2009, and $380bn between 2010 to 2014], to immunise the state against recurrent riots and protests".

'The population's opposition to Bouteflika in recent weeks should not obscure the fact that it was he, the man of the past, who shaped 21st century Algeria'

- State official who knew Bouteflika well

For journalists Hassane Zerrouky and Hassiba Mellouk, who contributed to the book, Our Friend Bouteflika - from dreamed state to scoundrel state, in 2010, Bouteflika's ambition was to "erase October 1988", when the multi-party system came into being.

Bouteflika wanted to "restore the autocratic state in which he grew [up]", the journalists wrote.

The president saw in the free press, autonomous unions and opposition parties "an intolerable transfer of sovereign prerogatives to an 'immature' population".

In 2004, he won the elections with 88.99 percent of the vote. After amending the constitution in 2008 to scrap president term limits, he won 90.24 percent of the vote in 2009 elections and 81.5 percent support in 2014.

"His critics believe that he was only a king shaped by the system," a state official who knew Bouteflika well told MEE. "They forget that he always lived in a world of power. He was convinced that taking and keeping power requires cunning and intelligence.

"The population's opposition to Bouteflika in recent weeks should not obscure the fact that it was he, the man of the past, who shaped 21st century Algeria."

- The article is an edited translation of a story that was originally published by Middle East Eye's French website.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.