How will the 'terrorist' designation for the revolutionary guards affect Iran?

In an unprecedented move, the administration of US President Donald Trump has added Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) – with an estimated 125,000-strong force – to the State Department’s list of foreign terrorist organisations.

This marks the first time the United States has officially branded another state’s military as a terrorist outfit. With its own air, ground and naval units, the IRGC comprises the most powerful component of Iran’s armed forces.

Partly meant to boost Trump’s domestic profile with a sizable constituency of right-wing and pro-Israel voters, the decision will also make engagement with Iran harder for actors such as the European Union – and raise the political costs of staying in the 2015 nuclear deal for the “centrist” government of President Hassan Rouhani.

Global military target

Blacklisting the IRGC was raised by Trump in a landmark 2017 speech, in which he called for “tough sanctions” against the entire organisation. The US Treasury Department identified the IRGC as a terrorist group, making any dealings with it subject to secondary sanctions.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

As such, the new designation as a foreign terrorist organisation will not have a substantial economic impact on the IRGC, or by extension, Iran. But the branding renders the corps and all its members a legitimate global military target, on a par with al-Qaeda and the Islamic State (IS) group.

Iranian hardliners who have traditionally been critical of the nuclear deal will find new ammunition to push for withdrawal

This will likely maximise political pressure on the major European powers – Britain, France and Germany – to further shy away from working with Iran on various policy matters. The same pressure applies to Iraq and Lebanon, two influential regional actors close to Tehran.

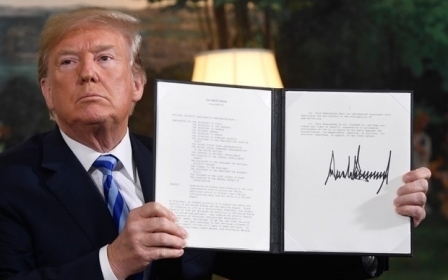

The European desire to engage in diplomacy with Iran is partly tied to the aim of keeping alive the nuclear agreement, which was dealt a severe blow last May, when Trump unilaterally withdrew from the multilateral accord and reinstated comprehensive sanctions against Tehran.

The EU sanctioned the IRGC in 2010 over Iran’s nuclear and missile activities, but with the new US designation in place and the departure of Britain from the EU on the horizon, sustaining support for the nuclear deal will become politically harder and more costly. The new label facilitates the process of prosecuting international persons and entities that do business with Iran.

Scrapping the nuclear deal

Iranian hardliners who have traditionally been critical of the nuclear deal will find new ammunition to push for withdrawal. The view that it no longer makes sense to adhere to the agreement is rapidly spreading, even among political factions that have supported the deal.

“There is no accord [left] for Iran to withdraw from,” Hamze Ghalebi, an Iranian reformist figure and former head of the youth headquarters of Green Movement leader Mir-Hossein Mousavi’s electoral campaign, told MEE.

In fact, the IRGC terrorist designation lends credence to the hardliner argument that Tehran should scrap the deal and resume nuclear work at a level more advanced than in the past, based on its core national security interests.

The primary reason Iran has restrained itself so far has been to avoid paving the way for the formation of a global coalition, including Russia and China, against it.

“Some reformists who were among the founders, or senior members, of the Revolutionary Guards in its inception believe, rather simplistically, that with sufficient reforms they can maintain [the] IRGC as a national asset,” Masoud Bastani, a pro-reform journalist and former political prisoner, told MEE. These same figures contend that the IRGC’s missile programme and overseas operations, “which help expand its hawkish influence in the region, act as a defence shield”, he said.

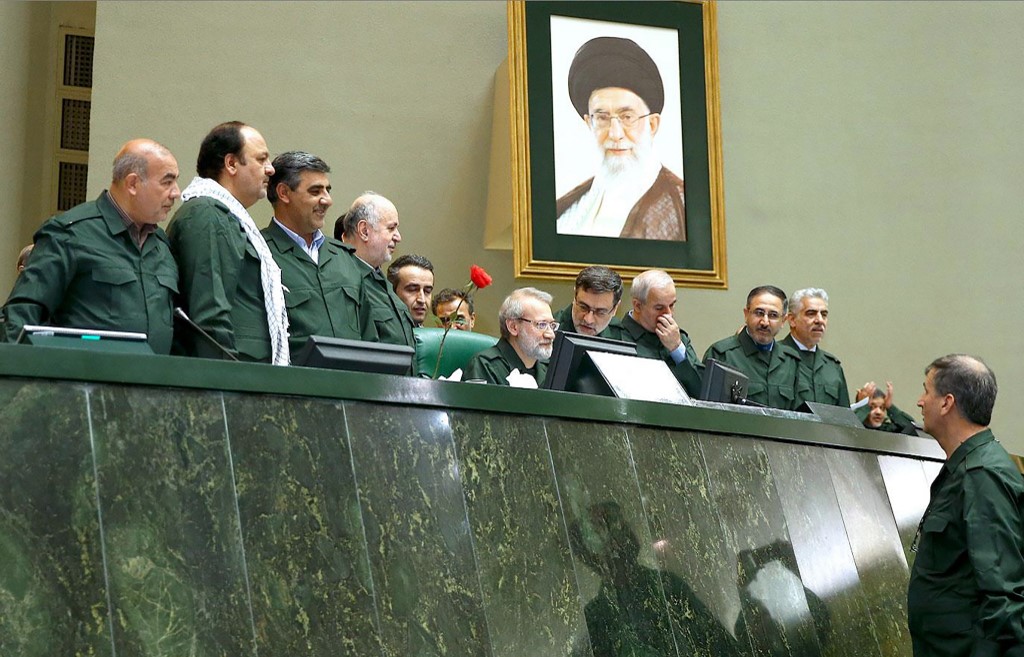

The sweeping ban is expected to change the prevailing critical discourse about the IRGC and consolidate this belief. It was, therefore, little wonder that many politicians and activists otherwise critical of the elite group immediately rushed to its support on social media, with lawmakers showing up in parliament in official IRGC attire the next day.

Indeed, the punitive measure seems to have aroused a nationalist rally-around-the-flag sentiment in parts of the Iranian polity and society alike.

Long-term implications

Beyond furthering Trump’s pro-Israel credentials at home and helping to facilitate another electoral win for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, the designation has long-term implications that will affect future US leaders.

It will likely tie the next president’s hands when it comes to potentially bringing the US back into the nuclear accord and, more broadly, seeking rapprochement with Iran, by making dialogue and diplomacy politically costly. After all, how can Washington legitimately negotiate with or accommodate the demands of a state whose military is officially designated as a terrorist organisation?

The blacklisting serves to entrench and institutionalise US-Iranian hostilities, setting them on a collision course. This is perhaps why senior US military commanders have long opposed the designation, amid concerns over a backlash.

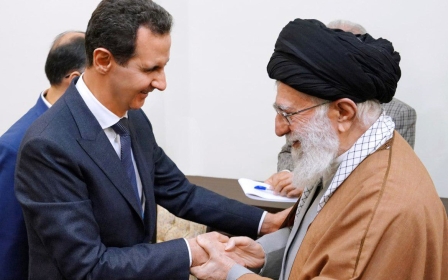

Hours after the White House decision was announced, Iran’s Supreme National Security Council blacklisted the US Central Command – responsible for military operations in the Middle East and Central Asia – as a “terrorist” organisation, while the parliament moved to table a motion designating the whole US military as a terrorist entity.

But despite already heightened tensions between Washington and Tehran, the chances of the IRGC directly targeting US forces in retaliation are “almost zero”, said Sajad Abedi, a senior analyst at Iran’s National Defence and Security think-tank, which is closely affiliated with Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s office.

Blunting US presence

At the same time, the Revolutionary Guards might rely on “grey forces” – those opposed to Iran's enemies but not necessarily allied with Tehran – to blunt the US military presence in the region, according to an IRGC-affiliated security analyst who spoke to MEE on condition of anonymity.

Coincidentally, three US troops and a military contractor were killed near Afghanistan’s Bagram Air Base in a roadside explosion claimed by the Taliban on 8 April, the same day the Trump administration announced the new IRGC designation. Two days later, Afghan local sources reported that the militant group shot down a US warplane over the southwestern province of Helmand, a few hours from the Iranian border, although the credibility of the reports has not been verified.

These incidents are curious and thought-provoking, considering ongoing peace negotiations between the Taliban and the US in Doha.

“[The] lack of any response on Tehran’s part may strengthen the [confrontational] position of American hawks, and weaken anti-war folks who have been warning about the huge costs of military action against Iran,” Ghalebi said. “In fact, leaving US [aggressive] behaviour unanswered means mainstreaming and encouraging proponents of war against Iran in Washington.”

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.